I was thinking this morning about two subjects that don’t usually go together, skeuomorphs and morality.

A skeuomorph is a design element applied to a product that looks as if it’s functional but really isn’t. Its real purpose is to evoke a sense of familiarity and comfort. The literary critic N. Katherine Hayles cites as an example the dashboard of her Toyota Camry, which is made of synthetic plastic molded to look as if it’s stitched fabric.

Software designers use lots of skeuomorphs for their user interfaces; examples include the “pages” that seem to “turn” in e-readers and word processing programs. Hayles calls skeuomorphs “threshold devices.” They “stitch together past and future,” she says, “reassuring us that even as some things change, others persist.”

For a few months last year Apple Computer took a lot of flack from the design cognoscenti for its dedication to skeuomorphs; the linen texture that appears as background on the iPod and the wooden bookshelf used for the iBook display were frequently cited examples. The company’s skeuomorph aesthetic was said to be a legacy of Steve Jobs, who was convinced people needed recognizable touchstones to ease them through the uncharted expanses of cyberspace.

Enough! cried the cognoscenti. The time for such reassurance has long since ended! So it was that cheers greeted the firing in October of Apple’s software leader, Scott Forstall, carrier of the skeuomorphic torch, as well as the introduction of Microsoft’s sleek new Metro Design, which doesn’t pretend to be anything other than pixels on a screen.

Although I’m pretty sensitive to the look and feel of things, my thoughts about skeuomorphs this morning had nothing to do with user interfaces. Rather I was thinking that perhaps the idea of a skeuomorph might be applied outside the domain of design, specifically to the realm of ethics.

It seems likely that in an era of mass-market technology morality has become – not always, but often – a skeuomorph: a feature that’s retained for the sake of appearances rather than any practical function. Any function, that is, other than that of reassuring people that even as some things change, others persist.

These admittedly dark thoughts were prompted by reading the recent cover story in the New York Times magazine, “The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food.” Reporter Michael Moss describes in brilliant detail the lengths to which America’s biggest food and beverage conglomerates have gone to design products we can’t get enough of, literally. Their profits and our waistlines get fatter. They prosper, we don’t.

Moss opens the piece by telling the story of an extraordinary summit meeting of food industry leaders, convened in Minneapolis in 1999 by a Pillsbury executive named James Behnke. Among those in attendance were the presidents or CEOs of Kraft, Nabisco, General Mills, Procter & Gamble, Mars, and Coca-Cola.

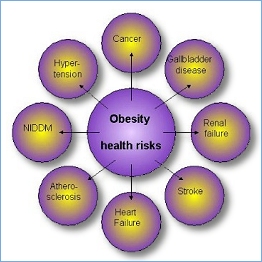

Behnke called the meeting to discuss the implications for their businesses of the nation’s skyrocketing rates of obesity. Health officials and physicians’ groups were sounding alarms: Obesity was a health-care catastrophe in the making, especially among children, and the products sold by the men at Behnke’s meeting were a major cause of the problem.

Behnke, a chemist with a doctorate in food science, believed it was time the industry addressed the obesity issue, not only because it was threatening to become a public relations liability, but also because the health officials and physician’s groups were right: the industry did bear some responsibility for undermining the health of its customers. His feelings were shared by a vice president from Nabisco named Michael Mudd, who presented to the assembled executives an obesity primer, describing with the help of some 114 slides the scale of the epidemic and the threat it posed to the packaged food industry.

Mudd then offered a series of recommendations. First, he said, the industry should acknowledge that its products were more fattening than they needed to be. Second, the industry should vow to do something about it. He suggested a three-step course of remedial action that began with a program of scientific research to determine what was causing people to eat more than was good for them. Once that was determined, the industry could reformulate its products to reduce their harmful ingredients and devise a nutritional code for its marketing and advertising campaigns.

It would be lovely to report that Mudd’s presentation was greeted with a standing ovation and an impassioned, consensual vow to go forth and reform America’s packaged foods marketplace for the sake of the people. That didn’t happen. According to Moss, the next person to speak was Stephen Sanger, who at the time was leading General Mills to record profits by selling just the sort of fat-, sugar-, and salt-filled products being blamed for the obesity explosion.

Sanger wanted no part of Mudd’s remedial program, or, for that matter, his guilt. General Mills had always acted perfectly responsibly, he said, not only toward its customers but also toward its shareholders. Consumers buy what they like, and they like products that taste good. General Mills was in the business of selling products that satisfy those tastes and had no intention of doing anything else. His competitors, Sanger suggested, should do the same. On that note, Moss reports, the summit meeting ended.

That these captains of industry would proceed, with endless creativity and ambition, to fill the shelves of American supermarkets with mountains of unhealthy, wasteful, dishonest products, knowing the pernicious effects those products would likely have on the well-being of millions of consumers, was the source of my dark thoughts this morning.

It’s hard not to conclude from examples such as these – and there are many others – that in the pursuit of corporate power moral restraint becomes – not always, but often – a skeuomorph, a decorative element that pretends, for reassurance’s sake, to be functional, but really isn’t. There’s nothing new about greed, of course. The difference is the scale of mendacity advanced technologies put at our disposal, and the ease with which checks on mendacity are discarded. The only justifications required: consumers will buy it and stockholders will profit.

The divorce of technology from morality is a theme that was sounded repeatedly by the philosopher who has most influenced my thinking on matters such as these, Jacques Ellul.

As I’ve explained elsewhere, Ellul pictured technology as a unified entity that relentlessly and aggressively expands its range of influence. Ellul used the term “technique” to underscore his conviction that technology must be seen as a way of thinking as well as an ensemble of machines and machine systems. Technique includes the methods and strategies that drive those systems, as well as the quantitative mentality that drives those methods and strategies. The invention, production, distribution, and marketing of addictive junk foods are all manifestations of technique.

The single overriding value of technique, Ellul repeatedly said, is efficiency. Worries about morality are obstacles in the attainment of efficiency, except where the brutality of efficiency’s pursuit causes concerns that might produce resistance, and interference. “It is a principle characteristic of technique that it refuses to tolerate moral judgments,” Ellul wrote in 1954. “It is absolutely independent of them and eliminates them from its domain.”

Moral “flourishes” remain, he added, but only for the sake of appearances. In reality, “None of that has any more importance than the ruffled sunshade of McCormick’s first reaper. When these moral flourishes overly encumber technical progress, they are discarded – more or less speedily, with more or less ceremony, but with determination nonetheless. This is the state we are in today.”

At the time of the food summit in Minneapolis, it’s clear James Behnke hadn’t fully acclimated himself to those conditions. Stephen Sanger apparently had.

(For a related post, see Autonomy continued: Technology or Capitalism?)

Doug Hill is a journalist and independent scholar who has recently completed a book on the history and philosophy of technology. This post also available on his blog The Question Concerning Technology.

Comments 2

Friday Roundup: March 15, 2013 » The Editors' Desk — March 15, 2013

[...] Cyborgology. In the next front of the Digital Dualism wars, Whitney Erin Boesel points out the “boys’ club” was never a boys’ club; SIM City’s big mistakes are bigger than Electronic Arts seems to think; and Doug Hill awesomely uses the word “skeumorph.” [...]

Has Morality Become a Skeuomorph? | Betteridge’s Law — April 26, 2013

[...] Has Morality Become a Skeuomorph? [...]