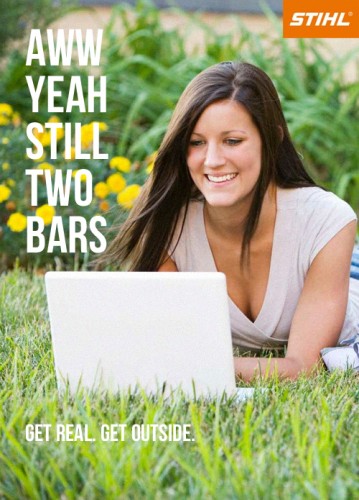

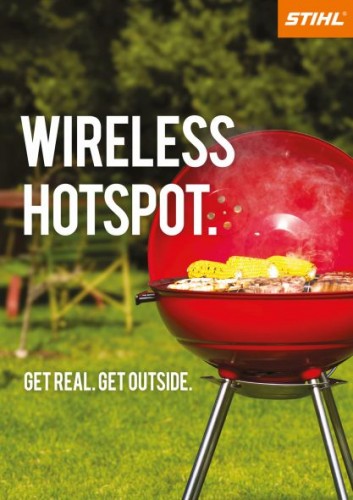

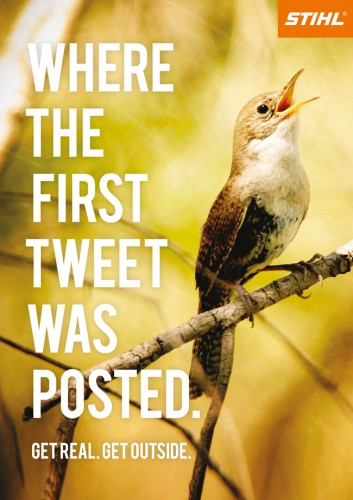

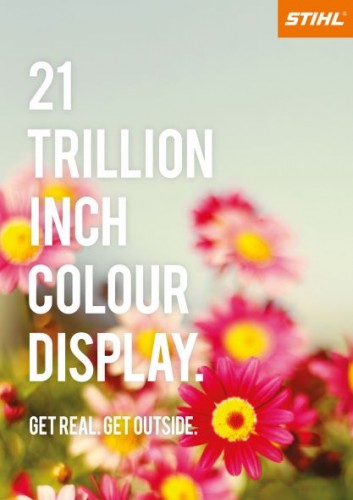

A recent marketing campaign from outdoor tool manufacturer Stihl is a classic – and pretty obvious, for regular readers of this blog – example of digital dualism. It’s right there in the tagline: the campaign presents “outside” as more essentially real by contrasting it with elements of online life. It not only draws a distinction between online and offline, it clearly privileges the physical over the digital. And through the presentation of what “outside” is and means, it makes reference to one of the most common tropes of digital dualist discourse: the idea that use of digital technology is inherently solitary, disconnected, and interior, rather than something communal that people carry around with them wherever they go, augmenting their daily lived experience.

But there’s more going on here, and it’s worth paying attention to.

First, Stihl isn’t only privileging the physical over the digital – the ads not only make reference to Twitter and wifi but to Playstations and flatscreen TVs. In so doing, Stihl is actually drawing a much deeper distinction than the one between “online” and “offline”; it is not-so-subtly suggesting that contemporary consumer technology itself is somehow less real. Stihl is questioning the legitimacy and worth of the whole of our relationship with our gadgets.

Pretty gutsy for a chainsaw company.

And I’d argue that there’s something else beyond even that going on here. These ads don’t merely draw a distinction; they issue an imperative. They order the viewer to alter their behavior, to leave their technology behind and embrace a more “real” existence “outside”. This is not only fetishization of “IRL”, but fetishization of the pastoral – the assumption that there is something more authentic, real, and legitimate to be found in the natural world than in human constructions.

This is actually a very old idea, and it can be found in art and literature going back to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, especially in America (though I should note that Stihl’s ad campaign is Australian). America’s relationship with what has been culturally constructed as “wilderness” is a fundamental part of our historical national identity, and the industrial boom of the 19th century and the subsequent erosion of that wilderness made a mark on the American psyche. As Michael Sacasas writes in his essay on “The Smartphone in the Garden”:

America’s quasi-mythic self-understanding, then, included a vision of idyllic beauty and fecundity. But this vision would be imperiled by the appearance of the industrial machine, and the very moment of its first appearance would be a recurring trope in American literature. It would seem, in fact, that “Where were you when you first heard a train whistle?” was something akin to “Where were you when Kennedy was shot?” The former question was never articulated in the same manner, but the event was recorded over and over again.

Sacasas goes on to note that in art and literature that deal with pastoral themes, the encroachment of industrial technology is often presented with a certain degree of gentle threat or melancholy; it’s a kind of memento mori for rural American life, and a recognition that the world is changing in some fundamental and irreversible ways. Inherent in this is a nostalgia for the American pastoral, a sense that life lived within that context was somehow better and more real, as well as more communal. The pastoral was fetishized in much the same way that “IRL” is now, and its perceived loss was mourned in ways that should be familiar to anyone who’s read Sherry Turkle.

There’s an additional facet of this kind of thinking that’s worth pointing out: the idea that not only is human technology somehow separate from, in opposition to, and less real than the natural world, but that humans themselves are somehow divorced from the natural world. Lack of technology brings us closer to some vague construction of what we imagine as our true nature; use of technology takes us further away. In this understanding of us, we can exist in the natural world but we are not of it, and we can leave it. We aren’t animals. We aren’t inherently natural.

That’s about as dualist as you can get, I think.

What’s especially interesting about Stihl’s ads in this context is that they’re an outdoor tool company – they exist to make instruments through which a human being alters and remakes their environment. If we make use of dualist thinking for a moment and consider “real” as a spectrum, with the completely unconstructed and untouched by humanity as one end and the entirely technological and digital as the other, then a suburban backyard is hardly “real”. It’s a landscape that has been constructed entirely for human use, and ecologically speaking, it’s pretty much a desert (actually not even that, given the ecological richness of deserts).

Stihl is therefore building its ad campaign on some arguably flawed assumptions. But they’re powerful assumptions, and they draw on powerful elements in a lot of Western thinking about the relationship between humanity and technology. This indicates some of why digital dualist thinking is so pervasive; it’s much older than the internet or the smartphone. In order to truly understand what it is and where it comes from, we need to be sensitive to not only humanity’s relationship with technology, but how we’ve historically understood humanity’s relationship with what we perceive as the natural world.

Comments 2

The internet IS real life. | NEXTNESS — August 20, 2012

[...] be fewer ads exhorting us to ‘Get real. Get outside.’As blogger Sarah Wanenchak says, Dear Stihl: I’m already real, thanks.Jessica Stanley is the Editor of Nextness. Some of her other Nextness posts include: Is the [...]

Dwolla Blog | Startup Crush: Coffee and Power — August 31, 2012

[...] called digital dualism, the separation of the online and offline world. It’s the idea that relationships [...]