I am working on a dissertation about self-documentation and social media and have decided to take on theorizing the rise of faux-vintage photography (e.g., Hipstamatic, Instagram). To start fleshing out ideas, I am doing a three-part series on this blog: part one was posted Tuesday (“Hipstamatic and Instagram”) and part two yesterday (“Grasping for Authenticity”). This is the last installment.

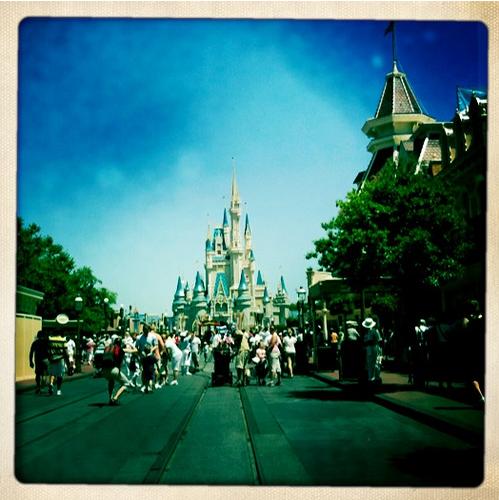

With more than two million users each, Hipstamatic and Instagram have ushered a wave of simulated retro photographs that have populated our social media streams. Even a faux-vintage video application is gaining popularity. The first two posts in this series described what faux-vintage photography is, its technical facilitators and attempted to explain at least one main reason behind its explosive popularity. When we create an instant “nostalgia for the present” by sharing digital photos that look old and often physical, we are trying to capture for our present the authenticity and importance vintage items possess. In this final post, I want to argue that faux-vintage photography, a seemingly mundane and perhaps passing trend, makes clear a larger point: social media, in its proliferation of self-documentation possibilities, increasingly positions our present as always a potential documented past.

Nostalgia for the Present

The rise of faux-vintage photography demonstrates a point that can be extrapolated to documentation on social media writ large: social media users have become always aware of the present as a potential document to be consumed by others. Facebook fixates the present as always a future past. Be it through status updates on Twitter, geographical check-ins on Foursquare, reviews on Yelp, those Instagram photos or all of the other self-documentation possibilities afforded to us by Facebook, we view our world more than ever before through what I like to call “documentary vision.”

Documentary vision is kind of like the “camera eye” photographers develop when, after taking many photos, they begin to see the world as always a potential photo even when not holding the camera at all. The habit of the photographer involuntarily framing and composing the world has become a metaphor for those trained to document using social media. The explosion of ubiquitous self-documentation possibilities, and the audience for our documents that social media promises, has positioned us to live life in the present with the constant awareness of how it will be perceived as having already happened. We come to see what we do as always a potential document, imploding the present with the past, and ultimately making us nostalgic for the here and now. And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

And there is no better paradigmatic example for this view of the present as always a potential documented past than the faux-vintage photo (why I have chosen this as a topic for essay). The faux-vintage photo asks the viewer to suspend disbelief about the authenticity of the simulated nostalgia and to see the photo–and who and whatever is in it–as being authentic and important by referencing at least the idea of the past. While, technically, all photographs, indeed all documentation, conjure the past, the faux-vintage photograph serves to vividly underscore and make even more clear our efforts to display our lives in the present as already a past to feel nostalgic for.

The faux-vintage photograph is self-aware of itself as document. If regular photos placed on Facebook walls document that we exist, the faux-vintage photo is this but also more than this: it is also a reference to documentation itself. This double document–a document of documentation–becomes further proof that we are here and we exist. The rise of faux-vintage photographs, snapped on smartphones and shared via social media, is centrally an existential move that is deployed because conjuring the past creates a sense of nostalgia and authenticity.

But the ultimate irony is that while these tools, just like all of social media, help us reinforce to ourselves and others that we are real and authentic, but they do this by simultaneously divorcing us to some degree from experiencing our present in the here and now. Think of a time when you took a trip holding a camera and then think of when you did the same without the camera; most of us have probably traveled both with and without a camera in our hands and we know the experience is at least slightly different; some might claim radically different. With so many documentation possibilities (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Yelp, Foursquare and so on), we are always, both literally and metaphorically, living with the camera in our hands. When discovering a new bar or a great slice of pizza we might think of posting a review on Yelp; when overhearing a funny conversation we might think to tweet it; when hanging out with friends we might create a status update for Facebook; and when at a concert we might find ourselves distracted by needing to take and post a photo of the event as it happens. When the breakfast I made the other week looked especially delicious, I posted a photo of it before even taking a bite.

My larger dissertation project will be to explore these points and demonstrate specifically how this newly expanded documentary vision potentially changes what we do. Does knowing that you will check in on Foursquare at least slightly influence what restaurant you’ll choose to eat at? In what other ways is our online documentation not just a reflection of what we do but also sometimes (or always?) a cause? To go straight to the extreme case, I once overheard a young inebriated woman on the subway around 2am state that “the real world is where you take pictures for Facebook.” She was, I thought, the smartest person on that train.

What Will Become of the Faux-Vintage Photo?

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Let me conclude this all by coming back to faux-vintage photos specifically. I think they might be a passing fad.

Faux-vintage photos devalue and exhaust their own sense of authenticity, which portends their disappearance because, as I described in part II, authenticity is the very currency by which they have become popular; there is an inflation as a result of printing too much currency of the real. For instance, the faux-vintage photo will no longer be able to conjure the importance associated with physicality (another point made in part II) if the vintage look begins to be more closely associated with smartphones than old photos. The novelty begins to wear off and the nostalgia fades away.

Most damming for Hipstamatic and Instagram is that these apps tend to make everyone’s photos look similar. In an attempt to make oneself look distinct and special through the application of vintage-producing filters, we are trending towards photos that look the same. The Hipstamatic photo was new and interesting, is currently a fad, and it will come to (or, already has?) look too posed, too obvious, and trying too hard (especially if the parents of the current users start to post faux-vintage photos themselves).

To be clear, photographic techniques like saturation, fading, vignetting and others are not essentially good or bad (for instance, I love these faux-vintage shots). But when so widely used they seem less like an artistic choice and more as if they are merely following a trend (what Baudrillard called the “logic of fashion”). The ironic fate that extinguishes so many trends built on suggesting and exploiting authenticity is that their very popularity extinguishes that which made them popular.

The inevitable decline (but not full disappearance) of the faux-vintage photo will be our collective decision that the style is beginning to appear increasingly posed, contrived and passé, and thus negating the feelings of authenticity that were the very reason we liked them in the first place. Another retro-looking photo of a sunny country road, a dandelion, or your feet?

check out part I and part II of this essay

Comments 34

Replqwtil — May 12, 2011

Excellent take on the role of social media in altering the very basic concepts which animate our day to day lives. I could almost see is as something like a "The more we live in real-time, the less we live in the present." kind of idea. I'm excited to see more about this concept of documentary vision in the future!

I'm also very interested in the role that it plays in affecting people's behaviours and choices, as mentioned here. Baudrillard's concepts of the code are very fascinating to me, and the role of social media in creating and enforcing such social codes through particular reproductions of forms of interaction through them, envoloping and dominating the social, seems like one of the most tangible examples of his theory.

Anyway, exciting stuff Nathan!

sally — May 12, 2011

"In an attempt to make oneself look distinct and special through the application of vintage-producing filters, we are trending towards photos that look the same."

Didn't I post that in the comments yesterday? ;-)

sally — May 12, 2011

Which means, that without differentiation (if everyone is using H and I), people will continue to innovate to be different--if that is their motive.

The key (for me) in your entire argument is determining whether this phenomenon is due to just making photos look "different" (the antique filters being one way to do that) a la "marking theory," as I posted yesterday also, OR if people are really feeling nostalgic for something that has a certain quality of "authenticity" (as you suggested).

I would argue that by virtue of holding up the phone/camera to take a photo, the person is already removing themselves from "grounded reality" and has entered cyborg space.

Perhaps the act of taking the photo, makes them miss the moment (because they are in "cyborg space") and they are nostalgic for THAT precise moment that they missed whilst taking the photo.

christine — May 12, 2011

"The explosion of ubiquitous self-documentation possibilities, and the audience for our documents that social media promises, has positioned us to live life in the present with the constant awareness of how it will be perceived as having already happened."

You've put words to something I've been thinking about for quite a while now. We are living less and less in the moment as we look not to the actual past but the POTENTIAL past. These types of photos are just one way that we as social media users create a landscape of nostalgia before the past has even happened. Your example of the photo of your breakfast is a perfect example. You didn't even eat it before it became a "document of the past" on FB.

Now I must go post some photos from my ipod to FB...;-)

Mike — May 16, 2011

Aren't you falling into a binary trap here, even after you (or Especially after you) document how our "cyber-activities" effect our "real world activities"? In part two you mention critiques of those that claim slacktivism and digital communication as inherently shallow, and yet isn't your thesis focusing on the inauthenticity, the forever chasing after,of self expression? Of course other people's photos on the web seem shallow and pathetic. I can't think of anything more boring than hearing other people recount their dreams or their acid trips, namely because they are not "real" to me but another's phantasmagoria.

At this point in history can we really understand the social implications of digital communication until we transcend this binary? I like that you are accepting the slipperiness, the endless acceleration of motion and fashion this "seeking after ....." inspires. But I think this motion inspires a strange brew of nihilism, and also precisly articulated and intense moments of real emotion. Just watch the video of Salem's screwd remix of Britney Spears. It will mean nothing shortly but it brought me to tears yesterday.

The SIP » The Faux-Vintage Photo Part 1: Hipstamatic and Instagram — June 3, 2011

[...] past. But we have a ways to go before I can elaborate on that point (see parts II and especially III of this essay). Some technological background is in [...]

pierscalvert — June 11, 2011

interesting read, and i agree with a lot of your conclusions, particularly the fact that this trend will fade and that the "vintage" aesthetic will start to lose its appeal. i do think it is verging on the contrived, but this type of photography does have some interesting benefits - notably, as you say, that you always have the camera on you to capture the moment. Also the camera is discreet and therefore gains you more intimate access to the subject, and IMO the square format is an easy format for the layperson to compose for, made even easier by the fact that it the viewfinder is a 2d screen not a 3d prism viewfinder; after all the genius of photography is essentially pre-visualizing a framing of the 3d world so that it be interesting to the viewer when seen in 2d... composing on liveview, iphone screen etc, makes it easier to see how the final 2d representation will look, because that's what it will ultimately be. Most interesting i think is the general perception that lo-fidelity photography is aesthetic (not just nostalgic), the fact that a photo often looks more interesting when the toning, coloring, saturation and so on is far distanced from reality. Hence the attractiveness of the film look compared to digital.

Hauntology: A not-so-new critical manifestation | Books in the News — June 17, 2011

[...] fiction and literary criticism. At its most basic level, it ties in with the popularity of faux-vintage photography, abandoned spaces and TV series like Life on Mars. Mark Fisher – whose forthcoming Ghosts of My [...]

Hauntology: A not-so-new critical manifestation | Great UK Blog – UK Finance, Technology, Business, Economy, Entertainment, Sports, Fashion — June 17, 2011

[...] fiction and literary criticism. At its most basic level, it ties in with the popularity of faux-vintage photography, abandoned spaces and TV series like Life on Mars. Mark Fisher – whose forthcoming Ghosts of My [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo » OWNI.eu, News, Augmented — June 22, 2011

[...] — Part II: Grasping for Authenticity Part III: Nostalgia for the Present [...]

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Briginfo — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Hopkins Local News — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Arden Hills Local News — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Deephaven Local News — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

AuxiliumRights » Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Articles — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Krantenkoppen Tech — July 12, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

TechMissus » Téléchargez vos instagrams avec Copygrams — July 12, 2011

[...] aller plus loin sur l’appel de Instagram, vous pouvez lire Nathan Jurgenson dans ” The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present #dd_ajax_float{ background:none repeat scroll 0 0 #FFFFFF; border:1px solid #DDDDDD; [...]

k — July 13, 2011

the filters are a emotional communicative aid more than an attempt to be unique or simulate authenticity.

a style-based memetic; the equivalent of an emoticon at the end of a sentence.

you have some good ideas in this series, but they seem incomplete and thus come across as cynical.

Week 46: Meeting the makers | Final Bullet — July 16, 2011

[...] I’m not already nostalgic for the present, I’m already excruciatingly ashamed of it. I go to conferences and meetings, and post my [...]

The Faux-Vintage Photo: Full Essay (Parts I, II and III) « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — July 17, 2011

[...] combines all three together. Part I: Instagram and Hipstamatic Part II: Grasping for Authenticity Part III: Nostalgia for the Present a recent snowstorm in DC: taken with Instagram and reblogged by NPR on [...]

Hauntology « ANDREW GALLIX — July 24, 2011

[...] fiction and literary criticism. At its most basic level, it ties in with the popularity of faux-vintage photography, abandoned spaces and TV series like Life on Mars. Mark Fisher — whose forthcoming Ghosts of My [...]

Xavier Matos — August 19, 2011

Great essay, I honestly never understood why anyone liked those faux-vintage photos but I think you hit the nail on the head there. Documentary-vision is a great label to describe that weird feeling we all get nowadays when we secretly wish someone was at the party to take fun looking pictures and post them up on FB

Copygram Lets You Download All Your Instagram Photos | Tech 2 Up — August 23, 2011

[...] If any other fans wants to “go deeper” on the appeal of Instagram, you can read Nathan Jurgenson’s take in “The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present.” [...]

Mirry — November 5, 2011

Interesting thoughts. As a photographer that uses these apps and will still create in the darkroom given the chance I feel the the term authenticity isn't really what it is I'm trying to achieve. For me photography has always been about the messages you create by composition and treatment of what's infront of you. It's a document of the person taking the picture more so than a document of the image on paper/screen.

I had not gone over to what I consider the dark side, (digital photography), until the iPhone. Still choosing the art of film over digital. These apps allow me the choices of what I would be doing in the darkroom in a fraction of the time and a fraction of the cost. I print these images onto paper and hang on walls not because I'm nostalgic for the past or even the present but because they speak to me on many levels. These images are still composed and considered in exactly the same way I would with film. No amount of filters or photo apps are going to make an uninteresting image interesting for the long haul. It's never worth applying a filter just for affect.

I believe that eventually these will be the snap shots and the authenticity of our time. The thing I think we miss out on are the happy accidents of film. We can keep the ones we like and can delete the rest, making our own history's a selected chosen record.

Die Fotofoto-Stilkritik: Ist Nostalgie wirklich von gestern? Eine Replik auf das aktuelle Hipstamatic-Bashing | fotofoto Blog — April 25, 2012

[...] überhaupt, da schließe ich mich der Analyse des Cyborgology-Autoren Nathan Jurgenson an, wird sich das Phänomen überleben, weil der Distinktionsgewinn, die der Look verspricht, von [...]

Rod — July 27, 2012

Fascinating article and discussion.

I'd like to make a point about why many people are treating every experience as something to potentially document. I think the huge proliferation of people posting, tweeting and otherwise publishing personal 'content' online to a non-targeted mass-audience has a narcissistic aspect to it. There's a bit of conceit and self-indulgence in assuming that complete strangers are going to be interested in your review of your local restaurant or your photo of the piece of toast you just made. I get the sense that there is a need to be noticed, a need to have as big an audience as possible. Put a bit simplisticly, it's a case of "I have an audience, therefore I am." People are assessing their own self-worth based on the size of their audience, rather than on the quality of what they're actually publishing. It's about valuing one's notoriety and fame over one's ability to produce "content" (photos, reviews, blogs, etc) that actually has merit and reveals evidence of some kind of thought, skill or expertise. For many, it's not about producing something of value for an audience, it's just about having an audience. So, I guess I'm just saying this phenomena of online self-exposure is just part of a wider cultural trend of valuing fame over substance.

The Faux-Vintage Photo Part III: Nostalgia for the Present » Cyborgology | iPhoneography-Today | Scoop.it — October 24, 2012

[...] [...]

Avant-Garde & kitsch | Tui Blog — February 7, 2014

[…] was better (essentially childhood.) Nathan Jurgenson argues that it’s an attempt to create a nostalgia for the present – an attempt to make photos seem more important, substantial and real. This yearning can lead […]