Yesterday’s SCOTUS ruling [full text] on Barack Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA or ACA) was an interesting one on several fronts. This post will go over political, legal, and health policy ramifications of the decision, focusing specifically on the individual mandate.

The Election

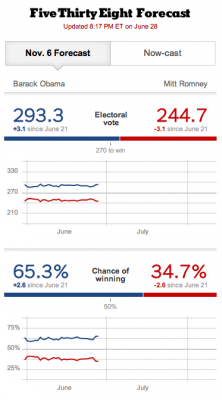

Earlier this year, I was of the opinion that regardless of the outcome of the case, Obama wins. Now, I’m not so sure that would have been the case. While a ruling against ACA would provide Barack and the Democrats election fodder by offering evidence of an activist conservative Court that is willing to override the will of Congress, I think a bigger danger would be tied to a divisive law that was a centerpiece to Obama’s first term that was deemed as unconstitutional. My opinion is that the electoral calculus favors Obama, but for him to be able to enact any change in his second term, he will need a mandate and enjoy Democratic control of the House and Senate. That might be a long shot. The trifecta of Presidency, House, and Senate is the real issue and precondition for an agenda of change—not the nationwide polling numbers, although perceptions of a close election are in the best interests of the media and could boost turnout, which would favor the Democrats.

Like Ike

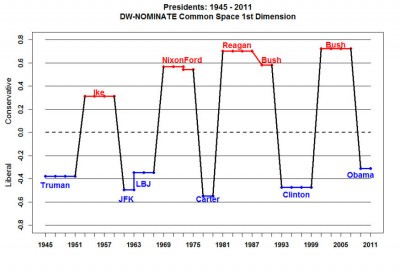

While Romney and the Republicans may try to make hay out of repealing ACA, I’m not sure how much traction it will get. It could be part of anti-taxation rhetoric, given that’s what the Supreme Court based the ACA decision on, but that could be problematic given that Romney has already committed to tax cuts for the wealthy. While some of Mitt’s recent political rhetoric has a populist ring to it, the devil’s in the details. I think in the battle for swing state independents and moderates, I think Romney’s only shot is to go populist and appeal with a middle-class populism. While Obama’s track record, based on Voteview’s analysis of roll call votes {albeit an imperfect measure for the presidencies}, shows him as the least liberal Democrat since Johnson {who was a hawk during the Vietnam War}, Eisenhower was the least conservative Republican.

Perhaps rather than harken back to Reagan, Romney should go back to 1950s traditionalism and the political moderation of Ike. I feel that Romney is allowing himself to be heavily defined by others—be it Obama or the more socially conservative wing of the party. Maybe this is a reaction to McCain’s maverick, seat of the pants style that involved choosing a Sarah Palin, who wasn’t always rowing in the same direction as the campaign, and suspending his campaign during the fall 2008 financial crisis. Addressing ACA as a moderate populist makes more sense than taking potshots at Obama’s “bad law” that is now deemed as constitutional. Plus, Justice Ginsburg stated Romneycare was a reason she sided with the majority, which can be thrown in Romney’s face.

Taxation vs. The Commerce Clause

While Chief Justice John Roberts is being lauded for his genius, this DC Bar post from January of 2011 presages his take on the matter. Jack Balkin of the Yale Law School is quoted:

“Balkin believes the best argument for the constitutionality of the individual mandate is that it is a tax. ‘It is an amendment to the Internal Revenue Code. It is collected on your tax return. It is collected by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). It’s computed based in part on your income. It’s a tax.’”

A commerce clause interpretation gets murky fast because it’s one thing for Congress to regulate commerce, but quite another to require it. Chief Justice Roberts [pdf] made this clear:

“Construing the Commerce Clause to permit Congress to regulate individuals precisely because they are doing nothing would open a new and potentially vast domain to congressional authority. Congress already possesses expansive power to regulate what people do. Upholding the Affordable Care Act under the Commerce Clause would give Congress the same license to regulate what people do not do. The Framers knew the difference between doing something and doing nothing. They gave Congress the power to regulate commerce, not to compel it. Ignoring that distinction would undermine the principle that the Federal Government is a government of limited and enumerated powers. The individual mandate thus cannot be sustained under Congress’s power to ‘regulate Commerce.’”

Tom Scocca in Slate argued that this could limit the ability of Congress to enact law through the use of the Commerce Clause. David Cole in The Nation isn’t so sure:

“When one adds the dissenting justices, there were five votes on the Court for this restrictive view of the Commerce Clause. But that is not binding because the law was upheld on other grounds. And while some have termed this a major restriction on Commerce Clause power, it is not clear that it will have significant impact going forward, as the individual mandate was the first and only time in over 200 years that Congress had in fact sought to compel people to engage in commerce. It’s just not a common way of regulating, so the fact that five Justices think it’s an unconstitutional way of regulating is not likely to have much real-world significance.”

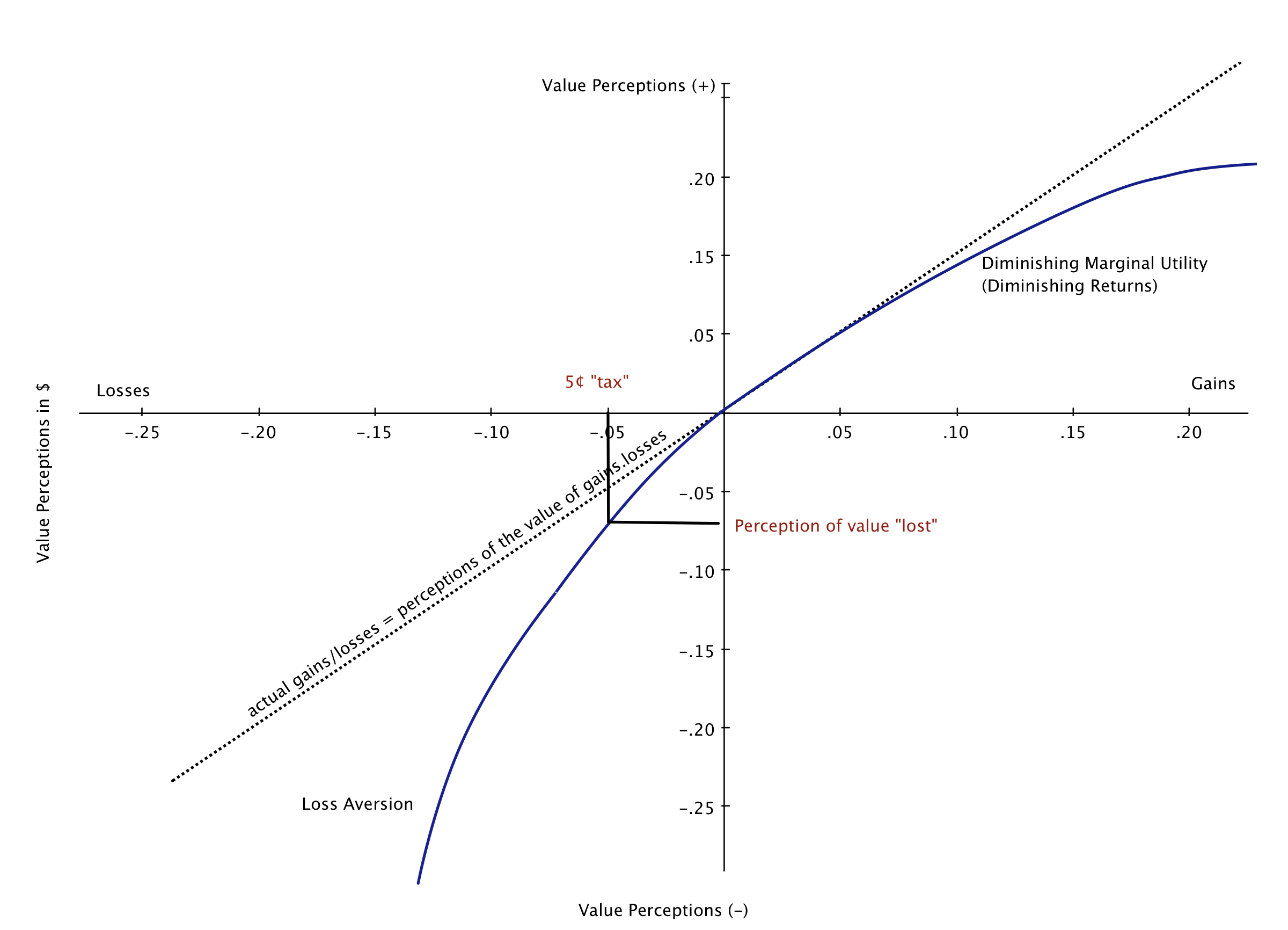

The ultimate policy effect of the “tax” or “penalty” will probably work because of social psychology’s prospect theory—people don’t like losses and will avoid them. This will compel compliance with the program, allowing the pooling of the population to spread out the risk.

Health Policy

Is the ACA good health policy? Well, one view is that it’s flawed from a health economics point of view, as Larry Van Horn states. I think he conveniently omits the fact that there’s a difference between actuarial and social insurance, which I blogged about on ThickCulture back in 2009. The healthcare industry faces uncertainty, as the increased demand for services may not be offset by pressures on margins. The main question for patients will be whether access to high quality care will be available. As a documentary producer and researcher on the subject of primary healthcare, I’ve been following what’s been done in Massachusetts, i.e., Romneycare. Yes, there are issues with rural healthcare in the Commonwealth and CUNY-Hunter College Public Health professors, David U. Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler {former Massachusetts MDs} are advocating for a public health program that would further reform healthcare. I think they make some very valid points, but I tend towards viewing healthcare as social infrastructure. Specifically, they are advocating for:

- Cutting out middlemen {costly insurance overhead}

- Pay hospitals based on costs, not on a per-patient basis

- Enforce real health planning

- More primary care, less specialists

- Price controls on pharmaceuticals

- Cap salaries on health executives

My take is that the ACA will have a positive net effect on health outcomes by increasing demand and adding to the insurance pool, younger patients who tend to have lower incomes [see pdf from US Census]. I think the best to hope for in the current model is a minimal care floor that serves as a lower threshold. It won’t be perfect and it may eventually move the industry towards rationalizing prices, which can be quite exorbitant, as evidenced in a LATimes report:

“Of course, and it’s all part of a years-long game in which the charge for service, the true cost of the service, and the acceptable payment are in three different orbits. And that doesn’t even take into account how the charges are adjusted up or down depending on who’s paying them and whether they have worked out a deal. How can patients hope to make sense of such an indefensibly convoluted system?”

Why? The insurance companies won’t be able to cherrypick healthy patients and will actively seek ways to cut costs. Although, they will most likely try to continue the practice of finding ways to limit payouts to physicians, I can see the insurance industry scrambling to develop new models of healthcare with segmented markets and there may be innovations stemming from the policy. The industry will push hard for as little regulation as possible.

Finally, who will be the big winners in all of this? In my opinion, the lobbyists. Oh, and mea culpa…{h/t Kathleen Maloney}