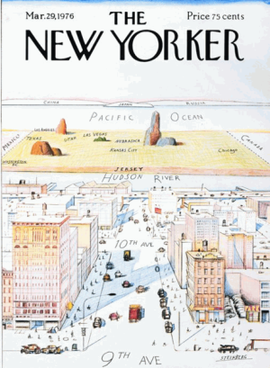

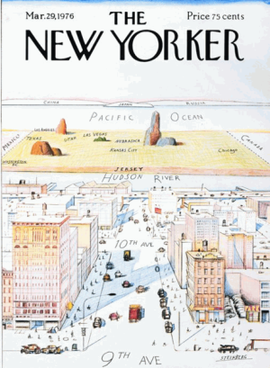

Six years ago, my wife and I moved to Fargo, North Dakota for my job at Concordia College across the Red River in Moorhead, Minnesota. Growing up in Bergen County, New Jersey, my view of the country looked a lot like the famous 1976 New Yorker cover, “View of the World from 9th Avenue.”

As a kid, a friend’s father tried to convince us that North Dakota didn’t exist (a take on the Bielefeld Conspiracy gag) and it seemed somewhat plausible. Even as I prepared to move, most of my understanding of Minnesota was informed by The Mighty Ducks and, like most people, what little I knew about North Dakota came from the Coen Brothers’ movie, Fargo. In other words, I was profoundly ignorant about the people, the culture, and the geography of our new home.

Six years later, in early June of this year, my wife and I packed up and moved back east to Saratoga Springs, NY for my new position at Skidmore College. In that time, I have had the pleasure of teaching many remarkable students and working alongside some wonderful colleagues. We have made lifelong friendships with people who are smart, progressive, and cosmopolitan, and who violate nearly all of the stereotypes of Midwesterners (except for calling soda “pop” — that’s actually real).

I’ve learned an incredible amount during these years and have come away with some perspective that I don’t think I would’ve had if I’d never left the East Coast. Here are four important things I’ve learned from living in the Midwest:

1. There is no Midwest. Ohio is different from Michigan, which is different from Minnesota. But Grand Rapids, MN in the Iron Range is also different from Minneapolis. Indeed, some of the identity of being an Iron Ranger is constructed in opposition to the culture of people from “The Cities.” While most Minnesotans and North Dakotans I know identify as Midwestern, evidence shows the percentages identifying as Midwestern are lower than for people living in Indiana. In my experience, North Dakotans especially are more likely to specify that they’re from the “Upper Midwest.”

But when it comes to understanding “the culture of the Midwest,” the divides of urban and rural, major city and small city are far more profound than the differences between Midwest and East Coast. The cultural difference between Chicago and NYC is smaller than the cultural distance from Minot, ND and St. Paul, MN. The caveat I would offer is that many urban dwellers in the Midwest are only a generation or two removed from a farm and tend to have greater familiarity with rural life than I have encountered in the East.

An important lesson to an ignorant East Coaster like myself is that “The Midwest” is far from monolithic.

2. If the American Dream is alive anywhere, it’s in the Midwest. With a little help from a 577 page surprise bestseller by a French economist with a name we’re stilling learning to pronounce correctly, we’re in the midst of a national conversation about inequality. It is now well-established that income and wealth inequalities are as great as they have been since the Gilded Age and that the extent of inequality is far greater in the U.S. than in Europe. Likewise (or perhaps consequently), the United States has much lower social mobility than Europe or Canada. Many social scientists and political figures alike fear that the toxic combination of high inequality and low social mobility seriously jeopardizes the dual promises of meritocracy and middle class prosperity that make up the American Dream.

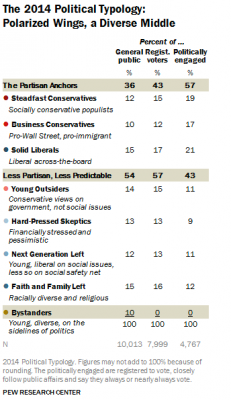

But social scientists have also shown the United States is not uniformly unequal. As the Equality of Opportunity Project has shown, the states of the western Midwest (WI, MN, ND, SD, NE, IA, MT) are among the most equal and socially mobile in the country (see figure).

Though I grew up with it, when I go back to New York or New Jersey now, I’m stunned by both the concentrated poverty and the extreme wealth. Fargo, a city of almost 200,000, has a booming economy and one of the largest Microsoft campuses and still can’t support a Banana Republic. Meanwhile, nine of the forty-five Gucci stores in America are within 20 miles of each other in the New York area. Of course, major Midwestern cities, like Minneapolis, have greater wealth and poverty, but they simply cannot compare to the intergenerational durability of wealth and permanence of poverty in either the Northeast or, especially, the South. If the American Dream of hard work and upward mobility is alive anywhere today, it’s in the Midwest (actually, it’s in Denmark or Norway where social mobility is much greater).

3. The Midwest has a deserved chip on its shoulder. The nation’s centers of power are on the coasts. The economy and the press are in New York. The government and military are in D.C. The culture industry is in L.A. And over half the nation’s population lives within 50 miles of a coast (39% live in coastal counties representing less than 10% of the country’s land (http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/population.html)). As a result, the Midwest (especially the Upper Midwest) is too often neglected. A snowflake falls in Midtown Manhattan and CNN flies into crisis mode. It takes serious devastation (or an absolutely massive oil boom) for the Coastal press to take notice of little ol’ North Dakota.

One of the more cringe-inducing experiences in Fargo is seeing a visiting band or comedian take the stage and make a hackneyed joke along the lines of “Wow. I’m in Fargo. It sure is cold!” And here’s the thing: the crowd eats it up! Because it’s a form of recognition. All that talk about the “real America” from the likes of Sarah Palin? Those are desperate cries that “hey, we count, too!” Especially in places like Fargo, what I’d call “place entrepreneurs” engage in active PR campaigns to show that life isn’t as bad as you think way out here (e.g., the #ilovefargo hashtag on Twitter started by a local urban promoter).

There’s a defensiveness in the region that stems from a real neglect and a feeling of disempowerment. On the other hand, it’s worth noting that feeling of disempowerment is somewhat counteracted by the highly disproportional representation that these largely low population areas have in Congress (Obamacare’s “public option,” for example, was taken out of the bill by seven Senators representing 3.6% of the U.S. population).

4. It is a Christian country in the Upper Midwest. An acquaintance, a mother of two small children, told me a story about her move from Connecticut to Fargo. She enrolled her kids in a non-religiously-affiliated day care in Fargo and when she picked them up during the middle of the day, she found that they were saying a prayer before snack time. None of the parents seemed to have a problem with it. She pointed out that in CT, the parents would have flipped out. Now, it’s not because everybody in North Dakota is a pious Christian, but because Christianity is so assumed as a part of everyday life that having a quick prayer shouldn’t bother anybody. The level of diversity in CT makes that unthinkable. As one of the chaplains at Concordia College once told me, “this is Christendom.” It does not operate at the level of aggressive evangelism (in fact, most people I knew are progressive Lutherans). Rather, Christian is taken to be the default category.

The two facts that define New York and New Jersey where I grew up are incredible diversity and extreme inequality. I grew up with a lot of secular Jews and, during the December holiday season, the schools took great pains to have as many menorahs as Santas. Like the rest of the country, all parts of the Midwest are becoming more racially and religiously diverse. So, Christendom is in decline even the Upper Midwest, but there is not the public secularity of the East or the West coasts.

—

To many Midwesterners, these points may be blindingly obvious, but they are things I couldn’t see as an East Coaster. From my conversations with other coastal folk, I’m not alone. So, thank you to my Midwestern friends who put up with a loudmouthed New Jerseyan and taught me more about my country. To my East Coast friends and family, let’s try to reject that New Yorker cover vision of America.