Science recently published a study done by its researchers in collaboration with the Information School at the University of Michigan that finds that Facebook isn’t entirely to blame for political polarization in the United States. It found that its own news feed algorithm has a small but significant effect on filtering out opposing news content for partisan users on Facebook. More importantly for the researchers, the algorithm did not have as strong an effect on filtering opposing news as users themselves. Predictably users on the far right and far left of the political spectrum filter their news content in line with confirmation bias theory.

Zenyep Tufecki already did a takedown of the sampling problems with the study. Here is the description of the sample from Science:

All Facebook users can self-report their political affiliation; 9% of U.S. users over 18 do. We mapped the top 500 political designations on a five-point, -2 (Very Liberal) to +2 (Very Conservative) ideological scale; those with no response or with responses such as “other” or “I don’t care” were not included. 46% of those who entered their political affiliation on their profiles had a response that could be mapped to this scale.

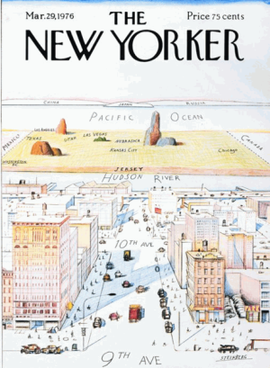

A key problem with this study is the standard problem of “selecting on the dependent variable.” By only sampling partisans, you are likely to find people who act in partisan ways when they evaluate news content. But my problem with this study runs deeper than selection bias. The study’s underlying assumption is that Facebook is simply a neutral arbiter of political information and it’s relevance is only applicable to those heavily interested in politics. In my view, Facebook’s influence runs much deeper. It changes the ways in which we relate to each other, and in turn, the ways in which we relate to the public world.

Facebook and related social media have created a seismic shift in human relations. Facebook’s platform takes conversations between friends, once regarded as “private sphere activity,” and transmutes it into what appears to be a public sphere for the purposes of serving the dictates of market capital. Facebook has created unique and powerful tools to allow individuals with the opportunity to more carefully “present themselves” to a hand picked circle of intimates (and semi-intimates). Facebook’s particular logic is connection and disclosure. More often than not, connection happens through expressive communication of feelings (pictures, observations, feelings, humor, daily affirmations, etc.). Facebook encourages us to “present ourselves” to our networks in order to form closer bonds with our friends and loved ones. It’s part of it’s business model. But we are in competition with others to gain the attention of our circle, so we are driven to use expressive discourse that is high-valence (e.g. strong attractive or aversive) content to gain the attention of others.

I argue in my 2012 book, Facebook Democracy, that Facebook constructs an architecture of disclosure that emphasizes this type of high-valence, expressive, performative communication. To Facebook, political content is simply one more set of tools we can use to “present” ourselves. If we want to use politics to connect with others, it needs to be impactful, expressive content that sends clear messages about who we are, not invitations for further conversation or clarification on public issues. This is not to say that people don’t argue on Facebook or have useful deliberative discussion, but I’d argue they do this in spite of Facebook’s goals. Argumentation or deliberation are not typically used to bring one closer to one’s friends and family.

While the personal and emotive is a key way in which we get into politics, staying engaged requires both expressive/connection based discourse and rational/deliberative discourse that encourages “listening” rather than simply “performing.” The notion that a “click through” necessarily means engagement with the ideas presented in “cross-cutting” articles suggest sharing cross-cutting/opposing articles is done in the spirit of deliberative discussion. More likely, cross-cutting articles are intended to reinforce an identity. More useful for Facebook scholars might be to look at instances where partisans are sharing cross-cutting articles and examining how they present the article. Are they presenting it and inviting mockery of it? Or are they inviting their networks into a conversation about it?

This is the key challenge that Facebook poses to democratic life. Rather than ask whether Facebook’s algorithm presents partisans with access to opposing views, we should be asking how we use political content on Facebook to present ourselves to others (and how we can do it in more productive ways). If Facebook and other media encourages expressive discourse over deliberative discourse, we run the risk of becoming a society of citizens that talk without listening.