An indulgent, self-promotion forthcoming… you have been warned!!

My new book Facebook Democracy is out and available through Ashgate press. Here’s a copy of the cover for you non-believers.

Tell you friends!!!

An indulgent, self-promotion forthcoming… you have been warned!!

My new book Facebook Democracy is out and available through Ashgate press. Here’s a copy of the cover for you non-believers.

Tell you friends!!!

Ken’s comprehensive analysis of the ACA ruling provides much food for thought. For the Obama administration, they get sorely needed legitimacy for their centerpiece legislation. In politics, winning is better than losing and it allows the administration to “move on” from what has been a difficult political struggle for them. It gives Obama the ability to forward a narrative of having “solved” a major social challenge… even if there are flaws with the legislation.

Romney can run on repeal of “ACA”, but as Ted Lowi observed in The End of Liberalism, policy drives politics. For starters, the old maxim of American politics — It is harder to kill legislation than to pass it, — hold true in this instance. Once you build a constituency for a program (narrow benefits), those beneficiaries will fight tooth and nail to keep it, particularly if those constituencies have political clout. Imagine a coalition of “ordinary Americans” lobbying against changes to the law that would remove the ban on insurers dropping coverage for pre-existing conditions. That’s chum for 24 hour news networks (maybe not Fox). Those who oppose the law on philosophical grounds, one could argue, won’t have the same intensity of interest once the law begins to take effect. Opponents of the ACA can spin all they want, but this was the best, and perhaps only, chance to kill the legislation.

Whether ACA is good policy has to be considered in reference to the “politics of the possible.” This Chicago-style, horse-trading style of lawmaking is how Obama envisioned governing in those dewy-eyed days of 2008-2009. The law isn’t optimal, but the mandate brought the insurance companies to the table and in exchange real people get to avoid the calamity of getting kicked off of their plan without a pre-existing condition. For that reason alone it is more equitable than our current system. It’s messy, irrational, and clientelistic. In other words, American politics at it’s best.

For better or worse, this is what social policy looks like. Indeed, Congress might need to revisit this issue after the election. One thing the court did strike down the ACA provision that would allow the federal government to withhold Medicaid funding to states that did not extend the program to %133 of the poverty line. This could have far reaching effects on the Federal government’s ability to use “strings” to compel states to go along with its mandates. While lots of speculation suggests that states wouldn’t turn down federal money to expand coverage, that money is only temporary. As as we’ve seen in states throughout the country, services for the poor and indigent are one of the first things to get cut during hard economic times.

For the moment, it is a progressive social advance… and a progressive dying of thirst in the political dessert isnt’ well served to ask for a lemon with a gift glass of ice water!

Back in early February, I speculated that Mitt Romney’s march to the Republican nomination might be derailed by his keen ability to create high negative valence moments. Video comments that reference how many Cadillacs his wife drives or how many NASCAR owners he knows can spread around the Web like wildfire and reinforce memes about candidates that are difficult to undo.

Daily Kos

The latest of these high negative valence moments is not a comment from Romney himself, but from one of his senior aides comparing his candidacy to an Etch-a-Sketch:

Well, I think you hit a reset button for the fall campaign. Everything changes. It’s almost like an Etch A Sketch. You can kind of shake it up and restart all of over again.

This probably is just a bump in the road, but if it comes to anything, it is because clips and parodies like the photoshopped Etch-a-Sketch above traveling through our personal and virtual networks lock in an idea of Mitt Romney as malleable. But then again, this isn’t news to anyone who as been paying attention.

Perhpas one of the Internet’s biggest paradoxes is between its ability to foster voice for those who might otherwise not be heard in society and the dangers that result from developing and presenting that voice to others. The tragic story of Kiki Kannibal, a Florida teen who recieved numerous threats and abuse from her provocative on-line profile, serves as a prime example of the challenges present in “putting oneself out there.”

On the other hand, Emily Nussbaum has a great piece in New York Magazine about the blogosphere as a vibrant space for a new generation of feminists. The feminist blogosphere has created a discourse space where young women are able to develop their identity as feminists and engage with ideas and, on occasion, mobilize against mysoginistic practices.

Somewhere embedded in this paradox is the issue of ownership of one’s personal presentation or the ability to be seen for who you think you are. While this is never guaranteed, more can be done in terms of ensuring that making snap judgments about people because of their on-line persona is limited. Helen Nisselbaum urges us to think of privacy on-line as being able to maintain contextual integrity or the extent to which information about a person is seen in relation to other relevant data.

Frank Pasquale recommends developing a system of governmental reputation regulation. Germany’s recent legislation prohibiting employers from using Facebook profiles to deny employment is a prime example of such regulation.

While this might address formal discrimination based on the misuse of on-line data, it doesn’t address the psychological harm of cyberbullying. Already we’re witnessing a ramped-up public service campaign designed to change norms around cyberbullying. Groups like stopcyberbullying.org are working to raise awareness about the harm that cyberbullying does. But these efforts need to be part of a broader campaign to teach digital ethics. To move people away from the idea that the on-line space is “a world apart” from their off-line lives.

At this year’s South by Southwest Conference, BBH Labs is playing homeless people in the city to carry wireless devices to serve as “homeless hotspots.” The blogosphere is having a tete-a-tete about whether this is patently offensive or a poorly designed effort to help the poor. Tim Fernholz notes that the program at least forces (Austinites?) to talk with the homeless.

Fair enough, I suppose. But at first glance, the juxtaposition of glimmering technology and human frailty bothers me. In “The Net Delusion,” Yvegny Morozov does a wonderful job of rebuffing the triumphalist rhetoric about the Internet “changing everything.” In his view, journalists waxed poetic about Twitter’s role in Iran because it fit a comforting narrative about those of us in the West:

Iran’s Twitter Revolution revealed the intense Western longing for a world where information technology is the liberator rather than the oppressor, a world where technology could be harvested to spread democracy around the globe rather than entrench existing autocracies. The irrational exuberance that marked the Western interpretation of what was happening in Iran suggests that the green-clad youngsters tweeting in the name of freedom nicely fit into some preexisting mental schema that left little room for nuanced interpretation, let alone skepticism about the actual role the Internet played at the time.

We want very much to believe that technology is the West’s gift to the world. That information spread freely will cure what ails the human condition. But as Morozov rather cynically points out “power is power” regardless of the technology. Giving homeless people these “jobs” is not democratizing or revelatory. It comes off as a triumphalist extension of what Morozov calls an “imagined revolution,” one in which technology is the conquering hero.

Jon Mitchell calls those participating in the “homeless hotspot” program “helpless pieces of privilege-extending human infrastructure.” A bit far maybe. The homeless have agency and might prefer this job to no job at all. But the optics of this program brings into contrast the chasm between technology and what it’s utopian adherents promise. In some ways, it makes clearer the limits of what technology and those who profit from it can, or more to the point, are willing to do to really be democratizing and emancipating.

I’m intrigued by the idea of the singularity. Given the exponential rate of technological change over the last four decades (a concept known as Moore’s law), who can predict the radical and unexpected ways that technology will change us in the next few years.

The idea of the singularity, that technological advance will proceed at such a pace we will soon have computers with “super intelligences” that will surpass our own, has appeal to many. As Jaron Lanier notes in his recent book, many who subscribe to this view believe that:

Computers will soon get so big and fast and the net so rich with information that people will be obsolete, either left behind like the characters in Rapture novels or subsumed into some cyber-superhuman something.

Lanier goes on to make the case that “We are Not Gadgets.” No “geek rapture” is imminent because information is inert without an intersubjective process of experiencing information. Computers cannot become smart enough to approximate inter-subjective feeling. He cautions us not to “deify information” and to look to “double down” on our own humanity.

But perhaps it’s our humanity that makes technology fraught with social challenges. The question for me is how we accomplish this process of preserving our humanity in the face of rapid technological change? As far as social media is concerned, I don’t entirely agree with Lanier’s view of technology as depersonalilzing us. I think it makes us hyperpersonal by further enveloping us in a world of personal feelings and subjective impresstions. I see the great challenge for humanity as technology develops is to learn the skill of standing outside of our own subjective milleu to see the “world out there.”

Sherry Turkle calls technology the “architect of our intimacies. What she fears is that technology will become so good at giving us that intimacy that we’ll come to see it as an extension of ourselves. As she notes in interviews she did with young people:

Teenagers tell me they sleep with their cell phone, and even when it isn’t on their person, when it has been banished to the school locker, for instance, they know when their phone is vibrating. The technology has become like a phantom limb, it is so much a part of them.

The personalization of technology isn’t because we deify it, it is because it caters to our vain sense of the preferability of our personal experience. If the machines rule us, it is because they flattered us with the possibility of ending loneliness and psychic want. The price may be the loss of spontaneity, contingency and the prospect of amassing wisdom from diverse experience.

What does it mean to pay for an idea? James Gliek reminds us that one of Google’s main business innovations was to:

let advertisers bid for keywords—such as “golf ball”—against one another in fast online auctions. Pay-per-click auctions opened a cash spigot. A click meant a successful ad, and some advertisers were willing to pay more for that than a human salesperson could have known. Plaintiffs’ lawyers seeking clients would bid as much as fifty dollars for a single click on the keyword “mesothelioma”—the rare form of cancer caused by asbestos.

While Google keeps its ads and its search results distinct, the lines between a “market meaning” and a “public meaning” are becoming blurred. With Google claiming two-thirds of the search market in the United States, does Google have a disproportionate power to define what things mean.

Google has a cryptic algorithm that relies on links from other authoritative and non-authoritative sites to establish page ranks. But as David Segal points out in the New York Times, these rankings are subject to manipulation through black hat search optimization. JC Penny was able to become the authoritative purveyor of thousands of products using this approach:

If you own a Web site, for instance, about Chinese cooking, your site’s Google ranking will improve as other sites link to it. The more links to your site, especially those from other Chinese cooking-related sites, the higher your ranking. In a way, what Google is measuring is your site’s popularity by polling the best-informed online fans of Chinese cooking and counting their links to your site as votes of approval.

But even links that have nothing to do with Chinese cooking can bolster your profile if your site is barnacled with enough of them. And here’s where the strategy that aided Penney comes in. Someone paid to have thousands of links placed on hundreds of sites scattered around the Web, all of which lead directly to JCPenney.com.

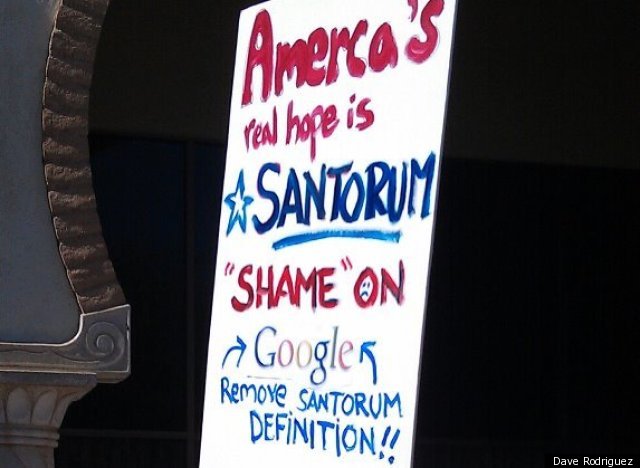

This might produce a big “so what?” if we’re talking about where to buy high thread count sheets, but what if we’re talking about non-commercial definitions. As an example, supporters of Rick Santorum have called on Google to remove an untoward definition of “spreading Santorum” aimed at lampooning his anti-homosexuality positions. While the original blog post with the link is no longer on the first page of search results, a search for the Senator’s name still produces ample references to “spreading Santorum” (links excluded).

While many readers will have little sympathy for his position on gay marriage, I’m sympathetic to supporters who seek to have some control over how the candidate is defined by people who search Google to learn more about their guy. Some might applaud this as a form of hactivism. But tampering with definitions is akin to having your worst enemy write an encyclopedia entry about you that sits right next to the entry you write about yourself. If Google increasingly frames how we “know the world,” then do the spoils go to those who know how to game the system.

Andrew Sullivan links to a chart from Paul Waldman at ThinkProgress showing a precipitous decline in gun ownership over the last few decades. What gives?

Kevin Drum in Mother Jones, points to a paradox between an increase in gun sales and a decrease in “households” that own guns. The comment section over there is particularly interesting.

To keep this all in perspective, we’re still a gun owning people. Compared to European nations, we own lots more guns per 100 people than any other nation.

Our own decline could just be the result of urbanization over the past three decades, but it could also be the result of a cultural shift towards what it means to own a gun. When I grew up, my dad had a gun but never told me where. I can still remember being little and being shaken by accidentally catching him putting it away by the nightstand in my parent’s bedroom. Having an instrument in the home that is so closely associated with the production of sudden death (for good or ill) has to impact everyone in the household. I’ve never seen good work on how gun ownership impacts one’s attitude towards life or towards the state. Does a gun owner, knowing what a powerful object they have in their possession, become more confident and self assured in their ability to “keep their loved ones or possessions safe” that they become more trusting of others and of centralized authority or does it serve as a “priming effect” reminding owners that human beings can be base and craven?

What does the crowd think? Does gun ownership and use change one’s outlook towards the world?

I start my forthcoming book Facebook Democracy with this quote from Carlos Castaneda’s mystical book Journey to Ixtlan where the Yaqui Indian Don Juan offers the young student some advice:

It is best to erase all personal history because that makes us free from the encumbering thoughts of other people. I have, little by little, created a fog around me and my life. And now nobody knows for sure who I am or what I do. Not even I. How can I know who I am, when I am all this? Little by little you must create a fog around yourself; you must erase everything around you until nothing can be taken for granted, until nothing is any longer for sure, or real. Your problem now is that you’re too real. Your endeavors are too real; your moods are too real. Don’t take things so for granted. You must begin to erase yourself

While I wouldn’t necessarily endorse this as a life’s goal, it is interesting to me to juxtapose this idea of “placing a fog around me and my life” with the demands of social media. It begs the question: where is the space for doubt, contingency and detachment in the world of social media. I ask this earnestly, fully recognizing that I might not “see the space” before my eyes. It is possible to be a “lurker” in social media, but from my conversations with students it seems like a frowned upon practice.

As a political scientist, what matters more to me is how “being too real” impacts our civic engagements with others. Does social media provide a “certaintly” about the world that inhibits our ability to make the detached observation necessary to appreciate the other? Or does it connect us more and thus make us more empathic and better able to appreciate the suffering of others? While a number of studies highlight how heavy Facebook users lead to greater levels of civic engagement through more exposure to diverse ideas and greater levels of interest in politics.

But is being exposed to diverse ideas the same as integrating diverse ideas into an uncertain and contingent self? An interesting study would look at how people deal with political information with which they disagree. Do they “unfriend” or “ignore” the information? Anecdotally, it seems people I’ve talked to simply remove people from their feed rather than un-friend them. How does engaging with different and potentially distasteful views change when the conversation is on Facebook rather than face-to-face? Not sure I know, but hopeful to find out in the future.

About an hour and a half ago, Google’s new Privacy Policy took effect which in essence will track and store all of your Goolge search activity…. if you wish to turn it off:

Users can turn off the setting that allows Google to record their search history. To get to this menu, go to www.google.com/history or head to the “Account Settings” menu from the top navigation bar you see when signed in to your Google account. Scroll down to the “Services” section. From here, you can pause, edit or remove all Web History. On some accounts, you can also go to the “Products” section of your account settings and click the “Edit” link next to “Your Products.”

How concerned should I be about all of this? Is this just natural business expansion or the beginning of the end for the company that “won’t be evil.”