If you’ve never had a chance to hear how the public relations industry in this country began, and how we got to where we’re at (e.g. much of modern “news” reporting is simply paid-for advertising by PR companies), take a look at what I believe is one of the very best presentations on the subject. In “The Century of Self,” Adam Curtis illustrates how the American father of PR, Edward Bernays, employed his uncle Sigmund Freud’s ideas in the US in the 1920s to change the way decisions are wrought at all levels of society. It’s one of the few times you’ll hear about the idea of “the mass-manipulation of public opinion” that is actually informed by a great deal of research and historical standing rather than self-satisfying, conspiratorial assertion. The series also speaks much to the nature of non-obvious propaganda that infuses American discussions of lifestyle, war rhetoric, etc. All four-parts of the riveting series can be watched immediately via Google Video.The Century of Self, Part 1

The Century of Self, Part 1 If you’ve never had a chance to hear how the public relations industry in this country began, and how we got to where we’re at (e.g. much of modern “news” reporting is simply paid-for advertising by PR companies), take a look at what I believe is one of the very best presentations on the subject. In “The Century of Self,” Adam Curtis illustrates how the American father of PR, Edward Bernays, employed his uncle Sigmund Freud’s ideas in the US in the 1920s to change the way decisions are wrought at all levels of society. It’s one of the few times you’ll hear about the idea of “the mass-manipulation of public opinion” that is actually informed by a great deal of research and historical standing rather than self-satisfying, conspiratorial assertion. The series also speaks much to the nature of non-obvious propaganda that infuses American discussions of lifestyle, war rhetoric, etc. All four-parts of the riveting series can be watched immediately via Google Video.

I’d like to highlight an extraordinary book, now two decades old, which I’m currently working through with my public affairs classes. It’s one of those books that, in my opinion, draws conclusions so sound and far-reaching for social and political life that I’m surprised I only stumbled upon it in a secondary source chapter in teaching communication theory several years ago. W. Barnett Pearce’s Communication and the Human Condition is an opus of insights into the communicative problems that wrack our planet, surveying the academic and professional convergences that have only begun to address what types of communication might be suited to humanity’s future. Despite our incredible technological and scientific advances, Pearce outlines how our evolutionary understandings of communication have remained at woefully underdeveloped (even premodern) levels, targeting particularly deleterious forms of communication that we see in everyday life (via chapters on monocultural, ethnocentric, modernistic, and neotraditional communication). The book finishes with a call to “the practicality of cosmopolitan communication,” based in many case studies that illustrate what forms of discourse might bring out the rich diversity in our different ways of being human, while retaining the tolerant coexistence necessary to any society. Overall, I would put Communication and the Human Condition on my top five list of books outlining the mindboggling complexities of human communication and action; if understood by more practitioners across the spheres of business, government, media etc., it could almost certainly create more equitable and informed institutions and practices.

I’d like to highlight an extraordinary book, now two decades old, which I’m currently working through with my public affairs classes. It’s one of those books that, in my opinion, draws conclusions so sound and far-reaching for social and political life that I’m surprised I only stumbled upon it in a secondary source chapter in teaching communication theory several years ago. W. Barnett Pearce’s Communication and the Human Condition is an opus of insights into the communicative problems that wrack our planet, surveying the academic and professional convergences that have only begun to address what types of communication might be suited to humanity’s future. Despite our incredible technological and scientific advances, Pearce outlines how our evolutionary understandings of communication have remained at woefully underdeveloped (even premodern) levels, targeting particularly deleterious forms of communication that we see in everyday life (via chapters on monocultural, ethnocentric, modernistic, and neotraditional communication). The book finishes with a call to “the practicality of cosmopolitan communication,” based in many case studies that illustrate what forms of discourse might bring out the rich diversity in our different ways of being human, while retaining the tolerant coexistence necessary to any society. Overall, I would put Communication and the Human Condition on my top five list of books outlining the mindboggling complexities of human communication and action; if understood by more practitioners across the spheres of business, government, media etc., it could almost certainly create more equitable and informed institutions and practices.

The depth and breadth of communication in New York City will never cease to amaze me. The sheer rush of sounds, bodies, lights, smells, and architecture that relentlessly impose themselves upon one’s self, from all directions, continually situate citizens in hybrid spaces between agency and structure, the familiar and the new. What has surprised you about public communication in New York or your own city?

There is currently a great deal of fanfare and criticism in the press over Clay Shirky’s new book, Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age, which celebrates the Internet’s achievements. The Boston Review sums up the book’s intriguing argument:

“Just as gin helped the British to smooth out the brutal consequences of the Industrial Revolution, the Internet is helping us to deal more constructively with the abundance of free time generated by modern economies. Shirky argues that free time became a problem after the end of WWII, as Western economies grew more automated and more prosperous. Heavy consumption of television provided an initial solution. Gin, that ‘critical lubricant that eased our transition from one kind of society to another,’ gave way to the sitcom. More recently TV viewing has given way to the Internet. Shirky argues that much of today’s online culture—including videos of toilet-flushing cats and Wikipedia editors wasting 19,000 (!) words on an argument about whether the neologism ‘malamanteau’ belongs on the site—is much better than television. Better because, while sitcoms give us couch potatoes, the Internet nudges us toward creative work. That said, Cognitive Surplus is not a celebration of digital creativity along the lines of Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman or Lawrence Lessig’s ‘remix culture.’ Shirky instead focuses on the sharing aspect of online creation: we are, he asserts, by nature social, so the Internet, unlike television, lets us be who we really are.” (“Sharing Liberally,” http://bostonreview.net/BR35.4/morozov.php).

The Los Angeles Times contrasts the book with Nicholas Carr’s thesis in The Shallows, which argues that

“even as we may be developing finer motor skills through constant Internet navigation, we’re losing the ability to focus for the significant periods of time necessary for deep thinking. . . . ‘[T]he news is even more disturbing than I had suspected,’ he writes. ‘Dozens of studies by psychologists, neurobiologists, educators, and Web designers point to the same conclusion: when we go online, we enter an environment that promotes cursory reading, hurried and distracted thinking, and superficial learning.’ Even more, he continues, ‘the Net delivers precisely the kind of sensory and cognitive stimuli — repetitive, intensive, interactive, addictive —that have been shown to result in strong and rapid alterations in brain circuits and functions.’ Carr has synthesized a wealth of cognitive research to illustrate how the Internet is changing the way we process information. ‘The Net is, by design, an interruption system, a machine geared for dividing attention,’ he points out. He is particularly disturbed by the Internet’s effect on our relationship with reading: ‘[I]n the choices we have made, consciously or not, about how we use our computers,’ he argues, ‘we have rejected the intellectual tradition of solitary, single-minded concentration, the ethic that the book bestowed on us.’” (“What is the Internet Doing to Us?”, http://articles.latimes.com/print/2010/jun/27/entertainment/la-ca-carr-shirky-20100627)

We have all been thrown into a communications revolution that seems to be advancing faster than we can make sense of it, and only time will tell what the sum of many of our technologies are doing to us while we‘re along for the ride. Yet we need to be attentive to communication about these unfolding matters as much as the unfolding matters themselves. Shirky and Carr are representative of the way a lot of discourse about the Internet is getting carved out between these two poles, so I’d like to highlight one idea that seems to be missing on both scores:

Shirky’s argument lacks a sense of the Internet as an individual activity and, more so, Carr’s argument lacks a sense of books as social activities.

This is not to argue that Shirky is wrong about possibilities for sociality on the web, nor to deny Carr the deep and needed solitude that books ought to provide. Rather, I think these debates we’re seeing unfold—and the policies they may entail—would be greatly advanced by examining how the Internet can be an individual activity and reading books can constitute a social activity.

The very words “Inter” and “net” don’t exactly help us see how the “web” may foster solitude; the terms assume we are all invariably connected. But solipsistic shopping sprees and Internet addiction camps testify to the medium’s individualizing possibilities (http://www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2007/November/Boot-Camp-for-Internet-Addicts.aspx). We can be clicking around an electronic cave as much as we’re addressing and being addressed by others online. Similarly, books often get cast as “solitary” and “single-minded,” but can equally been seen in terms of “deep engagement” and being “other-minded.” In The Company We Keep, Wayne Booth set forth an underused but highly heuristic image of the book as a conversational friend, given the medium’s ability to put one in dialogue with the extended and carefully chosen thoughts of another human being.

In other words, much current talk presumes the Internet necessarily opens discursive space for others while books provide a minimal mode of civic engagement. It strikes me that thinking a bit more about reverse assumptions would help Shirky better theorize the counterintuitive constraints under which creative efforts always operate (see Csikszentmihalyi’s Creativity) and help Carr frame his efforts in terms more conducive to where he seems to want to go: rather than focusing on others’ absence/presence, it may be that one’s way of being with others matters most.

Happy New Year everyone! I’m currently writing an article on how social media (Facebook, Twitter, blogs, etc.) are changing universities. I’m interested in how academic research, teaching, and service, as well as the administration, admissions, and other aspects of university life are being reconfigured (or not) in light of these new technologies. I’d like to open up a conversation and see if anyone has empirical or conjectural thoughts on this. Please let me know, as I’d like to cite others’ experiences or ideas if possible.

If it helps, I’m adapting McLuhan’s “tetrad” to interrogate this within the university context: What do social media enhance or intensify in universities? What do social media render obsolete or displace? What do social media retrieve that was previously obsolesced? What do social media produce or become when pressed to an extreme? – Don Waisanen

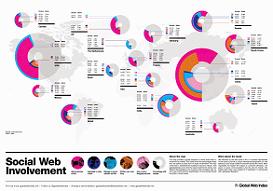

Check out this global map of social media usage: www.docstoc.com/docs/document-preview.aspx?doc_id=18486230

Adam Ostrow at Mashable.com highlights a few interesting findings from the report:

“The massive impact of China: The vast Internet population coupled with hugely socially active set of web users, makes for a massive volume of content creators. However due to the inward looking nature of Chinas internet economy combined with the language mean that this volume of content does not impact the broader Internet

Low engagement in Japan: We also associate Japan with technology innovation, and actual while you might not think it, the low engagement is indicative of progress. Why? Our map shows PC activity and we know from this research that a huge number of Japanese users are bypassing PC altogether and using mobile devices to access social platforms and create and share content. Just over 34% of social network users only accessed through mobile in the month of the research, this is compared to 3% in the UK, a staggering indication of where the future is heading.

The low level of microblog engagement: Despite the Twitter hype, microblogging is still not a mass social activity and nowhere near the size and scale of blogging.”

I’ve been discussing with a few friends the NY Times bestseller The Four-Hour Work Week (www.fourhourworkweek.com), which calls us all to less distracted work habits, to free up our time. Tellingly, however, the book seems equally as interested in pursuits like this: “Or forget about traveling. A brand-new black Lamborghini Gallardo Spyder, fresh off the showroom floor at $260,000, can be had for $2,897.80 per month. I found my personal favorite, an Aston Martin DB9 with 1,000 miles on it, through eBay for $136,000—$2,003.10 per month.”

I’m pretty ambivalent about the whole self-help genre of such books, which constitute a veritable industry unto themselves, but would be interested to know what others think. There seems to be definite inspirational value in such works—they can empower people with new visions and goals worth pursuing. As we know, such works can definitely “grow their own legs,” becoming “self-fulfilling prophecies,” of sorts (the key to “The Secret,” anyone…?). But my basic problem is that The Four-Hour Work Week provides a too partial, overly incomplete picture of how such dreams are made (this is before we even get to the value of the dream he’s setting forth), and in whose interests. That is, it’s a problem of looking at American public life accurately. By ignoring the systemic, structural, and social factors which can impede such opportunities, I think the author effectively neuters possibilities for political action by ignoring societal power dynamics.

One critical lens through which to examine such works may be Pierre Bourdieu’s “habitus”— roughly one’s deeply ingrained, acquired ways of speaking, acting, and being in the world inherited from one’s group/s, which act as signals of whether one is “in” or “out” culturally within certain contexts. If one has been fortunate enough to inherit the “preferred” ways of communicating in any given context, a four-hour work week becomes more of a possibility. If we ignore these dynamics, on the other hand, we will fail to see that the “the playing field ain’t equal” in terms of such opportunities–and the individual becomes the focus, without an understanding of the larger, material social forces which are also implicated here. Basically, the American authors of such books are failing to think in terms of sociology, instead assuming an individualistic default position for such writing that perpetuates power imbalances. — Don Waisanen

The other night I sat in on a new, lively reading group at our university discussing religion and modernity. We picked up Max Weber’s “Science as a Vocation,” as a way into these topics. I read this article in graduate school, but over the past couple of days I have found myself thinking more and more about this puzzling little piece. One passage in particular made me think about the Nobel Peace Prize going to Obama yesterday. Weber states that in an increasingly rationalized society there is a “disenchantment of the world,” as “the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life either into the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations.”

It would appear that the Nobel committee at least partially picked Obama for his renewed faith in public discourse to bring about peace and change in the world. Tim Rutten argues in the Los Angeles Times that the award was rightly given to the President for “words” rather than “deeds.” I would further argue the prize most appropriately went to Obama for finding a midway through Weber’s predicament in the above passage. Obama’s rhetoric has sought to enchant the political realm through sublime values that no human being can live without—for example, through the trope of “hope”. At the same time, these are values that are grounded in direct and personal human relations, or in abductive intersubjectivity rather than deductive, non-contextual assertion. There is much to critique in Obama’s administration, but it has at least evidenced an empirical concern for active listening and diplomacy as consequential in politics.

In one of his speeches, Obama espouses a faith in public discourse: “Don’t tell me words don’t matter. ‘I have a dream.’ Just words? ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’ Just words? ‘We have nothing to fear but fear its self’—just words? Just speeches?” At a minimum, Obama’s prior speech-actions have performed a role to which all those who love peace can aspire—enchanting the world with sublime but accountable words – Don Waisanen

Right now I’m exploring public deliberation on Facebook through an analysis of members’ writings about California’s Proposition 8. I entered the term “Proposition 8” on Facebook’s search function, analyzing the first 10 pages of wall postings on each of the first 50 groups created (examining only groups with over 25 members). Between the pro and anti-Proposition 8 sites, one clear finding has emerged—the opposition to Prop 8 engages the walls of pro-Prop 8 sites far more than vice versa (e.g. compare the walls of groups like “Repeal CA Proposition 8” with “Vote YES On Proposition 8!”).

Supporters of Prop 8 seldom write on the walls of anti groups. The pro-Prop 8 sites evidence a great deal of clash, however. For anti-Prop 8 advocates, Facebook groups appear to mostly offer spaces for testing and exploring arguments, that is, intra-movement advocacy. Occasionally a supporter of Prop 8 will write on an anti-site wall, but this usually consists of an isolated, inflammatory comment. Anti-Prop 8 advocates largely have to jump onto pro sites in order to engage in argument with the other side. My question is, what do you think explains this phenomenon? My initial thought is that anti-Prop 8 advocates are the ones with an uphill battle here, so they simply need to work harder to overcome the status quo. But that seems a bit surface and inadequate, given the sheer effort that the pro-Prop 8 supporters have put into their campaign. All in all, why is there more engagement by one side rather than the other on Facebook’s wall posts?