I’m teaching Internet and Politics for the first time since 2009. When I taught the course then, I was filled with optimism about the transformational potential of the Web. I assigned folks like Henry Jekins, Lawrence Lessig and Yochai Benkler, each in their own way preaching a gospel of societal salvation through the web (or at least a possibility of it), be it through convergence culture, free culture, or the networked information economy. But in 2012, this approach to teaching the course seems naively quaint. It’s not as if these authors were oblivious to the dangers of rationalization and centralization of the web, but each framed control over the Web as an open question. It seems much less of that to me…. Maybe that’s why Lawrence Lessig has moved on to study money in politics.

In his 2010 book, The Master Switch, Tim Wu captures the sense that the open Web is your father’s web, or at least your older brother’s web:

Without exception, the brave new technologies of the twentieth century—free use of which was originally encouraged, for the sake of further invention and individual expression—eventually evolved into privately controlled industrial behemoths, the “old media” giants of the twenty-first,through which the flow and nature of content would be strictly controlled for reasons of commerce.

Not that there’s anything wrong with commerce. But as Jaron Lanier skillfully points out, who makes money off of the Internet anymore?

Every few decades, a new communications technology appears, bright with promise and possibility. It inspires a generation to dream of a better society,new forms of expression, alternative types of journalism. Yet each newtechnology eventually reveals its flaws, kinks, and limitations. For consumers,the technical novelty can wear thin, giving way to various kinds of dissatisfaction with the quality of content (which may tend toward the chaotic and the vulgar) and the reliability or security of service. From industry’s perspective, the invention may inspire other dissatisfactions: a threat to the revenues of existing information channels that the new technology makes less essential, if not obsolete; a difficulty commoditizing (i.e., making a salable product out of) the technology’s potential; or too much variation in standards or protocols of use to allow one to market a high quality product that will answer the consumers’ dissatisfactions.

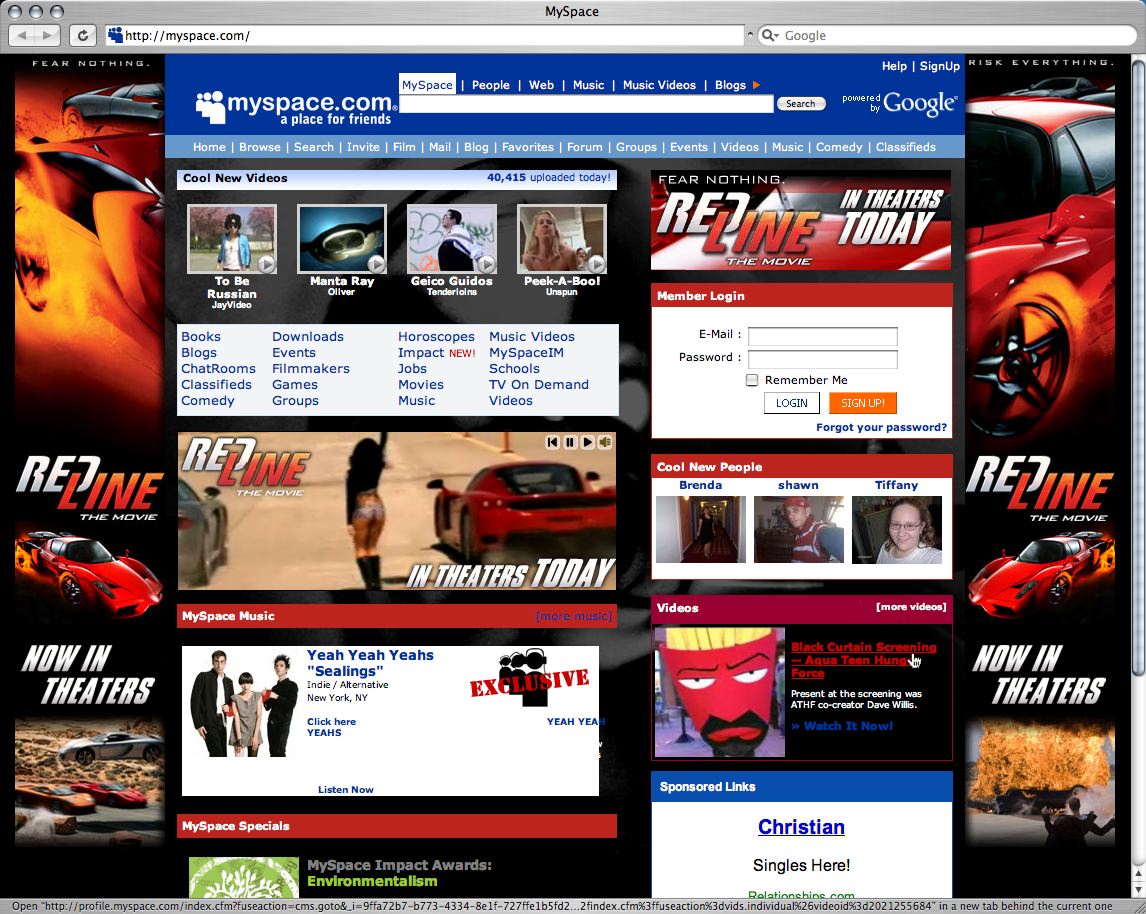

Who remembers the unpredictable “chaotic and vulgar” look of MySpace

compare that to the predictable clean look of Facebook:

Tell me if I (and Tim Wu) are being too cynical here? Is it Facebook’s fault if it just had a better design aesthetic than MySpace? So people want predictability, so what? Technology can’t change human behavior?

Comments