Widows tend to be invisible in modern society. Thus, it is ironic that when they reach the big screen in the film Widows (to be released in November, 2018), they are highlighted in the most outrageous and demeaning way. They are not depicted as valuable and grieving human beings, but as “gun molls,” a gimmick used to promote a stale plot genre. The only similarity the “gimmick widows” and real widows have in common is the loss of their husbands.

In the United States we live longer, but aging eventually catches us, and it creates a surplus of women who outlive their partners. According to the 2010 census, there were more than 11 million widows compared to three million widowers in the United States. About 700,000 women become widowed each year. Over 10 years, that makes 7 million widows (plus those who lose partners to whom they were not legally married). The 2020 census may well reflect a wider gap. And women are more likely to remain single than their male counterparts. Older men who outlive their partners are 10 times as likely to remarry as older women — 20 percent verses two percent.

As a widowed sociologist, I wanted to better understand widows’ experiences. I designed and carried out an exploratory study investigating how widows negotiate their new, and usually less valued role, in contemporary American society. I conducted in-person interviews with 20 widows, ages 55-80, from different socioeconomic classes and attended a widows’ support group for one year. The sample consisted of 12 White, 1 Hispanic, and 7 Black widows. The shortest time a woman was widowed was six months and the longest was 22 years, while the rest lost their husbands between one and nine years ago. Their incomes also ranged widely, from $11,000 a year to more than $150,000 a year. Only one widow stated that she was in poor health, three said they were in fair health and the remainder reported that their health was good, very good, or excellent. The respondents were also asked about their husbands’ last jobs before they died; they worked in a wide variety of occupations, including plumber, handyman, dentist, professor, among others.Initial Findings

One of my first and most basic findings is that “widow” is a hated description. The women I spoke with found it anachronistic, conjuring up “a little old lady” image. Maybe widows had been little old ladies in the past, but not now. Grieving for a beloved spouse, particularly after a long-term marriage is one of the hardest parts of life these women experienced. The grieving can be intense and last a long time. Before a widow could embark on her new single life, she was constrained by a wall of grief, and during this time she could accomplish almost nothing physically or mentally. One woman remembered being absolutely numb after her husband passed away. She literally staggered, physically unable to walk a straight line from one point to another.

Eventually the widows’ grief developed cracks, allowing them to take a few steps forward. Some of these steps were rewarding, though difficult, others were a mixture of good and bad feelings, and still others were disappointing. One of the most positive outcomes reported by the widows was their realization that they were more capable of handling their lives than they ever dreamed they could be. A few of the “newly uncoupled” commented on the bittersweet dichotomy of missing someone deeply and yet having complete freedom to do what they liked, when they liked. They found this dichotomy difficult but admitted that their self-images had improved and that they were becoming more self-reliant.

In many of the households, the husbands dealt with the finances, so handling finances added to the trauma of loss, even for women who were relatively well-off. So many details needed to be settled when the women were still grieving and unable to function at their usual level. Most of the women had not had any previous experience with Social Security, pension decisions and investing. Taking all of that on was a big deal. One woman in particular described slogging through the “financial stuff” as climbing a mountain. It was difficult to find footholds and the terrain felt treacherous. Yet, at the end, they managed.

When widows tried to reestablish some of their previous social activities, they did not always like what they found. Many felt betrayed by friends who were there for a week, and then “poof” — they were gone. If the widows lacked the energy or wherewithal to go out and look for something new, they felt alone, invisible, marginalized, and forgotten. Modern life can be very isolating.During their married lives, two institutions — the church and university — had acted like villages before their partners passed away. For religious widows, the church continued to feel like a village, with congregants acting like family in times of need. These widows felt embraced by a loving group and attuned to God. One particularly religious widow even said that if you asked her whether she had mourned her husband’s death, she might say, “no” because she remained close to God and to her family. Several church-going, lower socioeconomic widows from minority communities believed that their husbands were with God, waiting for them. For those who were not believers, family was the biggest part of their support system, particularly children and siblings. A few widows did not have good relations with their families and they had a harder time adjusting to their new status and new life.

However, the university did not serve the widows in this study as well as the church. Though wives of faculty members were welcomed while the husband was alive, when their husbands died, their existence was erased — even after years of being involved in college activities. In an organizational setting, once a dead husband has been taken off the company’s list, his wife becomes “defunct.” One widow was particularly hurt by her “excommunication.” An established professional in her own right, she had helped her husband with his work over the years. After he died, she felt that she had stopped existing to his colleagues because she never received one piece of mail that was sent to his workplace, and several formerly important social contacts ceased. Instinctively, she felt that something about widowhood made widows invisible. This was a frequent but not universal experience. At another university, the widow of a prominent faculty member unexpectedly still received invitations to talks and dinners.

Uncertainty often results because no universal norms exist that govern the behavior or expectations of the widow, or those in society with whom she interacts. In cases where there are no commonly agreed upon rules, individuals make up their own rules based on their life experiences. Even the idea of a widows’ policy — a policy that spells out the rights widows have regarding their continued involvement in some social occasions and speaker events — is alien to some. When one women who had attended spousal activities for many years, suggested to a board member that they needed to have a widows’ policy, she was asked, “What is that?” Another male administrator asked whether they had any widows before. Of course, once they became invisible, nobody would remember if there were any.

Finally, my most unexpected finding was that none of the widows I interviewed wanted to remarry. Their reasons fell into four categories: fear of losing another partner, wanting to keep their new-found freedom and independence, lack of interest in becoming a caretaker again, and worries about spousal abuse. For several upper-middle class women, who conducted their personal and social lives as a unit, the death of their spouses was so painful that they were unwilling to lose yet another husband. In another case, one minority, lower-income woman surprised herself when she realized she valued her new freedom so much that she was leery of considering remarriage an option, not expecting a second husband to allow her as much leeway. Some women also worried about “nurse or purse”– shorthand for believing that men wanted someone to take care of them financially, physically, or both. Apprehension was another factor. A low-income short-order cook who was aware of spousal abuse in her community, put it this way, “you know what you got, but you don’t know what you’re going to get.” Further, widows in this study did not find older men, in general, to be very interesting or attractive. They found women to be better companions.Conclusion

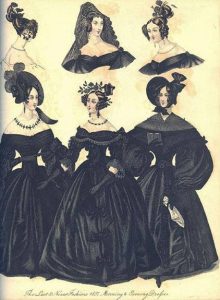

Throughout history, widows have been constrained by the conventions of their time. In the Victorian age, distinct guidelines for a woman’s dress and behavior were promulgated. If the widow was affluent enough, she was expected to wear “widow’s weeds” and restrict appearances in public for a year, living mainly within the confines of her family. When these women did venture into the public, they had to cover their faces with veils. The costume set the woman apart, making them both visible and invisible at the same time.

No such clear-cut rules guide widowhood today. Widows are uncertain about how they are supposed to act and how they will be judged in social situations. The transition to widowhood is unsettling. Dispersed across the country, families no longer provide the sanctuary and daily love and nurturing available when siblings and parents were more likely to live close by. Moreover, women are governed by expectations that differ depending on cultural, educational, and economic backgrounds. Singles often feel marginalized and isolated, and the hundreds of thousands of bereaved women who lose a partner each year may feel particularly estranged after the trauma of 24/7 caregiving.

What is the likelihood that being a widow will stop being an outlier and gain a valued role in society? While becoming “suddenly uncoupled” for Americans is increasingly common, the plight of middle-aged and older widows is just beginning to emerge as a topic of societal interest. Many are woefully unprepared for the transition and few societal norms exist to help guide them in their new life circumstances. Perhaps a bond based on the shared, painful experience of loss, despite cultural differences, may create pathways for American society to include them into mainstream society.

In the Trump era, efforts to highlight the needs of widows seem unlikely to happen at the national level, but there is hope for these changes at a state or local level. Organizations, like senior citizen centers and adult education schools, can offer workshops for widows to help them integrate back into society as singles. Local newspapers could provide information about Social Security benefits and how to apply for them. Further, human resource personnel can develop outreach programs explaining what pension and health coverage, if any, a widow is entitled to. Finally, media could feature widows in television shows and movies — for instance, imagine a soap opera based on an older widow negotiating her way into a prominently coupled society. But until we pay greater attention to the plight of widows, they will continue to struggle in a world that privileges couples. Hopefully the legacy of animals marching two by two into Noah’s Ark will eventually diminish and the numbers one and three will no longer be odd.

Recommended Readings:

Helena Znaniecka Lopata. “Widows.” Encyclopedia of Death and Dying.

Helena Znaniecka Lopata. 1996. Current Widowhood: Myths & Realities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Diane Rehm. 2016. On My Own. New York: Knopf.

Sheryl Sandburg and Adam Grant. 2017. Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy. New York: Random House.