Editors’ Note: This piece is reprinted with permission (and appreciation) from the site GazillionVoices.com.

I’m a 41-year-old adopted Korean American, and my son is a four-year-old African American adoptee. When I look at my son’s face, I think about how beautiful he is. I think that I’m grateful to have adopted such a wonderful little boy. I also occasionally think about how I was exactly his age when I was separated from my birth parents and sent thousands of miles away to a distant country that spoke a foreign language and where a strange group of people would become my new family. I don’t remember much from that period of my life, but when I reflect on it as an adult, I feel that it must have been difficult, right? Wouldn’t that experience be traumatizing and shouldn’t I have an ongoing sense of loss? Maybe this experience led to some of my personal failings, such as my anger issues? The fact that so many adoptees not only adjust but can even thrive after undergoing the adoption process speaks to children’s resiliency. Adopting my son certainly didn’t resolve any of these issues, but it did help me make sense of my life in important ways. It also shed light on an entirely new role: being an adoptive parent.

My son’s experience with adoption was worlds apart from mine. I was born in 1972 in Seoul, Korea to my mother, who was a poor young factory worker. She was unmarried, and my birth father left my mother before she gave birth. I stayed with her and my maternal grandmother until I was four instead of being put up for adoption immediately after my birth. I like to think that during this time she tried as best as she could to raise me herself and make it work. However, I can only conclude that, due to her precarious economic situation and the stigma and hardship single mothers in Korea face, she eventually gave me up for adoption. A Korean social worker noted on my adoption papers:

He is a quite pleasant and active child who is very friendly with others. He shows vivacity in playing with other children and can express himself verbally very well and is a quite thoughtful and generous child who can be hardly seen among children about his age. And he is a very easy child to deal with who is bright and clever and he likes to help his maternal grandmother in their daily lives. He is very fond of his maternal grandmother and mother’s sisters and he is loved by them. He likes to play with his bicycle [something I enjoy today] and rides it quite well and can manage his daily activities, such as going to the toilet and eating meals [tasks that I still feel pretty confident about!]. He likes to learn simple songs and also sings quite well [currently, I can’t and do not sing at all] and enjoys drawing things with crayons and pencils.

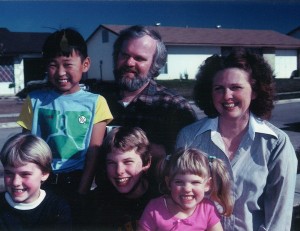

That little boy being described sounds like a complete stranger. Eventually, I was adopted by a white Minnesotan family and instantly had two siblings (an older brother and an older sister) and eventually a younger sister who is one of my parents’ three biological children. At that time, adopting interracially seemed to be an inconvenient by-product of adopting from Korea that my parents were wholly unprepared and unequipped to handle. They rarely, if ever, acknowledged or spoke about race generally or my Korean background specifically. The only conversation I can recall about Korean heritage or culture was my now-deceased father mentioning that I tried kimchi once and wasn’t fond of it. (I have made a concerted effort to eat it now, and while it certainly isn’t my favorite Korean cuisine, I’m growing more accustomed to it.) I also recall my adoptive grandmother telling me about surgical procedures to get my eyes “fixed.”

While my adoptive parents provided me with a loving and stable home and more financial security than my birth mother could have likely provided, my wife (who is African American) and I are committed to having a more open dialogue about race and ethnicity with our son. We recognize racial differences and discuss them openly. Even now, he understands that he is Black, and I am something else (he doesn’t totally understand “Asian” yet, and it’s only been recently that he has stopped saying that I am white). We don’t presume that if our son needs or wants to discuss race then he will come to us. We actively facilitate the conversation about race; he’s too young now, but we’ll discuss with him how racial prejudice and discrimination impact African Americans in the United States and how they might impact him. Especially in the wake of Trayvon Martin, we’ll discuss the types of assumptions many people will make about him and the types of precautions that burden young Black men when they venture into public spaces. While these frank conversations about race may be more common now for adoptive families, they were absent in my childhood.This approach to raising my son is in part informed by my experiences with being an Asian American man in the United States. For me, this has meant loathing the film Sixteen Candles, tolerating small penis jokes (I never understood why everyone, including other young boys, were so obsessed with my penis), sighing every time I see Asian women with white men, and ultimately wishing I was white and hating myself and other Asians I knew throughout my adolescence and young adulthood. One of my primary goals as a father is to foster an environment that acknowledges racial differences as a source of pride instead of shame and insecurity. This approach to raising my son also stems from my profession as a sociologist who studies race and inequality (my focus is on crime and punishment). Just about every day, I read about, teach classes on, or conduct research concerning the importance race continues to have in the United States. I understand how a lack of opportunity can diminish an individual’s potential as a human being, and that success in the United States is increasingly unrelated to hard work and desire and instead a product of who our parents happen to be.

In fact, part of why I wanted to adopt a child is because adoption for me is social justice. It’s a way to provide a human being with the opportunity to fulfill his or her potential, whatever that is. On a more personal level, adopting my son felt karmic. It was a way for me to give the universe the same thing the universe gave to me—an opportunity. Of course on top of all this, my wife and I wanted a child and felt ready for one (or as ready as one could feel), but I eventually found out that my son would give me more than I had imagined.

Our social worker told us that black boys are the most difficult foster children to permanently place, which we found saddening but not surprising. In fact, some potential adoptive parents explicitly stated they didn’t want a black child and would wait years to get a non-black one, despite the overwhelming supply of black children in the foster care system who need a home. In June of 2011, our social worker told us that there was a child who she thought would be available for adoption if we were interested: a 2½-year-old African-American boy. He had been with a different foster family for the previous 18 months. His current foster mother didn’t want to adopt him, and the state was already undergoing termination of his birth mother’s parental rights. She was struggling with drug addiction and mental illness and had been in and out of correctional facilities much of her adult life. At that time no one knew who his father was, but we later discovered his father had tragically died shortly after his son’s birth when he was 22 years of age. We’re not sure if my son’s birth father ever knew he had been born. We told our social worker we were very interested and took him into our home and adopted him about seven months later.

In the past two and a half years, my son has grown into a sensitive, sweet, smart, funny little person. He tells me stories about his days at school, and he tells me that he can’t eat small pickles because they are too cute. Every morning he wakes me up by crawling into my bed and lays his head on my chest. He’s an amazing swimmer and loves the Transformers. He is one of the best things that has happened to me. But adopting him has changed my life in ways I hadn’t expected.

As previously mentioned, it is important for me that our family openly recognize, discuss, and celebrate racial differences. I want him to embrace and accept who he is. How could I teach my son to accept and be comfortable with himself if I couldn’t do the same? Shortly after my son’s adoption, I made a concerted effort to explore my Korean heritage. I’ve fully jumped on the hallyu (the exportation of Korean pop culture) bandwagon. I’m taking Korean language classes at a local university. I’m also planning to return to Korea for my first time next summer. (My best friend knows other adopted Korean Americans who have experienced something similar and refers to it as a “Koreisis.”) While getting to know what it means to be Korean, I’ve begun to accept and even take pride in my racial and ethnic background. Adopting my son has helped free me from trying to run away from myself. Some of these changes were slowly happening already. Just getting older and ostensibly wiser has led me to be more comfortable with who I am. Yet adopting my son forced me to face these issues honestly and with purpose.

Comments 5

Diana — December 5, 2013

This was very touching to read.. All the happiness to your family.

Ryan king — December 17, 2013

Thanks for sharing this Darren... it was moving (seriously). And your son is right... just buy some bigger pickles!

Paul — December 25, 2013

Thank you for sharing a great experience... I live in Korea and I was lucky enough to be involved with many Korean adoptees who have come to Korea to teach English. There is an government organization situated in Seoul that supports Korean adoptees. If you are not aware of the organization I would be happy to let you know where they are located and put you in touch with them.

Warm wishes to your son and your family.

Paul — January 28, 2014

Darren, this website should be helpful for you: http://ikaa.org/en/