It hasn’t been hard to find media coverage of the role that religion played in the 2016 presidential election. If you have been following the news at all, you know that evangelicals voted for Trump in record numbers, helping to push him to an Electoral College victory.

Except they didn’t.

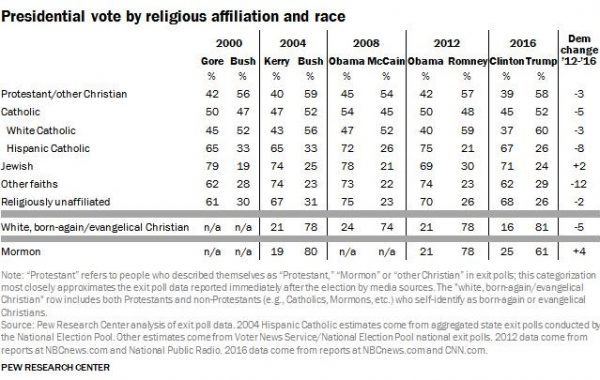

White evangelicals voted for Trump – and at a higher percentage than for any presidential candidate in recent memory. The graphic below is from Pew Research’s post-election report, “How the Faithful Voted.”

About 75% of Blacks are Black Protestant, and Black Protestant churches often embrace evangelical religious beliefs. Due to the way Pew conducted its post-election voting analyses, it’s difficult to find the percentage of Black evangelicals who voted for Trump, but a different Pew report reveals that 88% of Blacks who voted supported Clinton, and only 8% supported Trump.

Putting the information from the two reports together, it is very clear that being evangelical did not lead voters to support Trump. Race was a far more important driver than religious belief in this election, a pattern also evident in the racial divide among Catholics, with 60% of White Catholics voting for Trump and only 26% of Latino Catholics doing so.The key to understanding the coalition that swept Trump to power involves understanding that White evangelicals voted for him because of the particular way in which their racial interests and religious beliefs intersected. It also involves understanding that, for many other White Americans, the White evangelical rhetoric about morality struck a responsive chord, uniting a large plurality of voters anxious about the preservation of a White, Christian cultural heritage. Part of that cultural heritage involves a preference for traditional gender roles and a mistrust of a particular kind of White liberal feminism; Mike Pence’s reference to a “strong, broad-shouldered” leadership in the VP debate was no accident. Trump ran as a strong, White, male, Christian-friendly leader – and that was enough to win.

The media did not completely miss the race story. The Atlantic had an excellent long-form article on how the 2016 election revealed racial “fractures” within conservative Christianity, and several stories featured the modifier “White” before the word “evangelical” in the sub-headline, if not the lead. But Time was not alone in burying the racial story, in an article that conflated the general term “evangelicals” with the racially-specific “white born-again voters.” The New York Times did the same thing. Laurie Goodstein, in her election report, wrote about how Ralph Reed and the Religious Right mobilized support for Trump, then mentioned, in passing, that the 26% of the electorate she earlier termed “evangelical” is really comprised of White evangelicals. Goodstein even briefly noted the racial divide within the Catholic vote, before switching back to a discussion of a generic Christian vote driven by religiously based moral concerns.

Coverage like this implies – and sometimes states directly – that White evangelicals voted for Trump primarily because their religious beliefs about abortion influenced them to place potential Supreme Court nominations over other considerations in their vote. The implication is that, while other parts of Trump’s coalition may have voted based on racism, xenophobia, or economic interests, “the evangelical vote” was a moral one.

Most sociologists of religion, too, have approached the study of religion primarily as the study of belief. In this, they reproduce insider understandings of religion taken from reformed Protestantism. Protestants fight over doctrine – beliefs matter, and religious persons are understood first and foremost as believers – and individuals are seen as making morally accountable decisions to rationally affirm or reject particular doctrinal statements. As I’ve written previously, in an article reviewing social scientific research on religion, this way of thinking is helpful for understanding evangelicals, but distorts the role that religion plays in the lives of people from other religious traditions.Americans, in general, respect religion. They take its influence on civic and political life seriously, in large part because they understand religious people as disinterested. That is, Americans see religion as being about morality and ethics, which they think of as separate from – or even opposed to – economic and political interests. Whether it is voting or leading a march, Americans tend to assume that religious persons are acting not out of self-interest, but in an apolitical adherence to the larger public good, as Rhys Williams and N.J. Demerath III showed in their analysis of religious political activism in Springfield, MA. Actions based on religious belief are understood as moral by definition – rooted in values that transcend particular economic or political concerns, and operating outside of identity politics.

One of Trump’s most popular campaign trail tactics was railing against “identity politics,” a term widely understood by his supporters as a code, and evoking resentment toward groups that many White Americans believe have benefited disproportionately from establishment politics and long-standing support of the Democratic party – Blacks and Latinos, immigrants and feminists, queers and especially same-sex couples. If, as Steven Lukes argued, one of the most fundamental bases for social privilege is cultural (specifically, the power to define oneself and others as social and political actors), American White evangelicals have had the privilege to culturally code their own identity as anchored in universal moral concerns and others’ identities as “merely” political. Sociologists of religion have often cooperated; the most influential study to date, by Christian Smith, uses the generic label “evangelical” to talk about White evangelicals, and calls the group a “bellweather” that represents America as a whole, uncritically reproducing an insider identity claim.

The facts are relatively simple. Evangelicals of all races are more likely to say that abortion is morally wrong, and to favor restrictions on access, than are other Americans; these effects are larger for Hispanic Americans than for the population as a whole, while Blacks are at the general population mean on these measures. But only White evangelicals supported Trump in the presidential election. To attribute their support to religious beliefs and views on abortion is to mischaracterize how their religion shapes political mobilization. Religion is not a matter of disembodied belief, separate from other aspects of identity. As we have shown in our work on the American Mosaic Project here at the University of Minnesota, race, gender, education, age, and other aspects of a person’s identity and social location shape the effects that religious beliefs have on their social and political attitudes. This is especially true when it comes to racial attitudes, as I’ve argued in new work published with Jacqui Frost.

White evangelicals may have core beliefs that are expressed in racially neutral terms, as Michael Emerson and Christian Smith have argued. But as we have shown through the American Mosaic Project, White evangelical culture serves as a cultural code that helps White Americans form symbolic boundaries that exclude non-White racial minorities. It helps foster a tacit, symbolic racism that labels non-Whites as morally problematic, just as it serves as a cultural code that fosters exclusion of atheists, Muslims, and others who challenge the primacy of a particularly Christian cultural heritage.Beyond this, however, there is a broad “cultural preference” for Christianity in the United States that extends far beyond the 25% of those who identify as evangelical Protestant. In our Boundaries in the American Mosaic Project survey (2014), 51% of Americans told us that being Christian is either “very” or “somewhat” important for being a good American, and 55% either said that America is a Christian nation and that’s a good thing or that it’s not a Christian nation and that’s a bad thing.

A cultural preference for Christianity shapes attitudes toward racial and religious out-groups, and it allows members of the Christian majority to draw symbolic boundaries that exclude racial and religious minorities as morally problematic. It also influences many who have little use for religious institutions per se but who are nostalgic and resentful of the loss of White Christian cultural dominance. Importantly for the 2016 election cycle, this cultural preference for Christianity spans lines of social class and includes many of the economically marginalized voters whom Trump targeted in the Midwest.

Reporters, sociologists, and others who want to understand the role that evangelicalism played in fostering support for Trump must ask why racial groups who share religious beliefs diverged in their voting behavior. In the case of the 2016 presidential election, it seems clear that White evangelicals voted for Trump based on their racial interests – just as Blacks and Hispanics voted for Clinton based on theirs. Where we talk only about White evangelicals’ religious convictions, paying no attention to racial motivations, we perpetuate a culture of White privilege that systematically denies that Whites, too, have racial identities and interests.

To see the White in Christian America, we must look past religious belief, and focus on socially embedded and intersecting racial, religious, and gender-based identities. Moral concerns are inherently political when they have to do with the preservation of a valued way of life, when they encode racial and other forms of privilege, when they appeal to a higher authority to justify patriarchal views no longer shared by the majority, and when they tie xenophobic concerns to religious rhetoric about Christian nationhood. Trump may not know that it’s spoken as “second Corinthians” and not “two Corinthians,” but details like that mattered little to the White evangelicals and White Catholics who so deeply hoped that Mr. Trump would make good on his promise to restore that which has been lost.Recommended Readings

Penny Edgell. 2012. “A Cultural Sociology of Religion – New Directions.” Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 38:247-65.

Penny Edgell, Douglas Hartmann, Evan Stewart, Joseph Gerteis. 2016. “Atheists and Other Cultural Outsiders: Moral Boundaries and the Non-religious in the United States.” Social Forces 95(2) 607–638.

Penny Edgell and Eric Tranby. 2010. “Shared Visions? Diversity and Cultural Membership in American Life.” Social Problems 57(2):175-204.

Michael O. Emerson and Christian Smith. 2000. Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Arthur Farnsley II. 2012. Flea Market Jesus. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books.

Jacqui Frost and Penny Edgell. Forthcoming. “Distinctiveness Reconsidered: Religiosity, Structural Location, and Understandings of Racial Inequality.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (accepted, in press).

Robert P. Jones. 2016. The End of White, Christian America. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Steven Lukes. 2005. Power: A Radical View. 2nd Edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Christian Smith. 1998. American Evangelicalism: Embattled and Thriving. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eric Tranby and Douglas Hartmann. 2008. “Critical Whiteness Theories and the Evangelical ‘Race Problem’: Extending Emerson and Smith’s Divided by Faith.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47(3):341-59.

Rhys Williams and N.J. Demerath III. 1991. “Religion and Political Process in an American City. American Sociological Review 56(4):417-31.

Comments