The Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) just became the first major sport to return to holding live events since the COVID-19 stay-at-home shutdowns. In doing so, the UFC bucked the precedent set by other sports determined to put safety first. The story behind the UFC’s decision to resume fighting reveals a lot about the various social pressures sporting organizations and authorities are struggling with and against in trying to return to action.

In one interpretation, Saturday’s fight is the story of a barn-burner, an event where the crowd remains standing, echoing every punch, cheering every submission and stands as a template or model for what we might expect from other athletic events in coming weeks and months. Yet UFC 249’s numerous back-and-forth exchanges and jaw-dropping finishes occurred before an empty arena, something unprecedented in the history of prizefighting, as UFC President Dana White announced at the post-fight press conference. On the other hand, by pushing forth in the midst of a pandemic, then, the UFC might be burning the barn, extinguishing the possibility of sport serving as a model of a safe and responsible return to “normal.”

And whether you care about sports or not, this sports story provides us with a narrative microcosm of the competing actors, interests, and social forces wrought by the pandemic and some of the possible pathways that lie ahead.

Backstory

Back in early March, White told reporters on ESPN’s Sports Center that he had spoken to President Donald Trump and that Trump did not think there was any point panicking about the coronavirus. White reported, “They said be careful, be cautious, but live your life and stop panicking. Instead of panicking, we’re working with health officials and the government.” But mere days later, NBA player Rudy Gobert tested positive for the coronavirus minutes before a game, pulling players directly off the court and suspending the season indefinitely. Within the week, most other major organizations, including the NCAA, NHL, MLB, followed suit in respect of local and state guidelines.

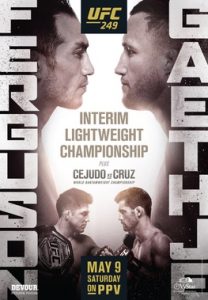

Cooperating with unions, these leagues quickly turned to developing plans to return when it’s a safer environment for everyone. The only outlier? The UFC, a promotional organization that lacks unionization and funds its fighters via lump purses. On March 14th UFC in Brasilia aired on the main ESPN channel, one of the only live sports being shown around the globe. This defiant production was marked by meager fan enthusiasm, scoring the lowest average viewership numbers for UFC on ESPN to date. Nevertheless, White maintained that he would not cancel the lucrative pay-per-view (PPV) of UFC 249, a bout scheduled for April 18th in Brooklyn between reigning champion Khabib Nurmagomedov and number-one contender Tony Ferguson.

As the world witnessed exponential growth of COVID-19 cases, however, White begrudgingly canceled the next five fight cards. During the process, he moved the planned location of the PPV at least two times, including to a tribal casino in California, and a never quite geographically specific “Fight Island.” Finally, he landed on Jacksonville, Florida, a state in which Governor DeSantis declared the WWE and the UFC essential. In the main event, Justin Gaethje had to fill in for Nurmagomedov last month after he was stranded in Russia. Gaethje continually abused Ferguson with 145 significant strikes until the referee mercifully waved a TKO in the fifth-round, and he was awarded the interim lightweight belt.

Texts and Models

In our time without sport there has been much reflection on what we are missing – health, community, escape, purpose, and all that other great and sometimes grandiose stuff. The gap in activity has also created space for critique and reimagining the role of sport in our lives. For some, this time offers a reminder that sport is not the most important thing as politics, the economy, the family, and health all demand attention.

We fall on the other side of things, believing that sport matters a great deal and as such reveals a great deal about the circumstances of the world of which it is part. During times of isolation, division, and uncertainty, sport has a unique ability to tell us stories that help us make sense of our culture. In analyzing the decisions made by the respective sport leagues, the question becomes, what story is being told to and about society. And, in the first months of life with COVID-19, there were a number of high-profile examples. When the entire NBA dramatically shut down on March 11th after a single player tested positive, this told an important story about how serious the situation actually was. For many this was the turning point towards taking the pandemic seriously. In contrast, the reluctance of the International Olympic Committee to officially postpone the 2020 games until numerous countries withdrew offered a tale of greed and exploitation.In arguing for the importance of sport, we take inspiration from the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz. In his classic study of the Balinese cock fight, Geertz describes the life or death competition and the betting that surrounded the technically illegal matches as a prime case of “deep play” to describe the heavy investment people make in games and activities that have seemingly little utilitarian value. For Geertz, the “deep play” of any sport or artform reveals key themes and qualities of society that matter almost precisely because they are not entirely rational. While the reader does not approach sport with the same intentionality as picking up a book, the text nonetheless captures and illustrates key themes in a manner that offers both a model of what society is and a model for what society could be.

The Cultural Stew

So. Back to the fights. From the perspective of sport as serving as a model of society, or in other words, reflecting key themes from society, it is not surprising that the UFC is one of the first sports to return. Dana White has been particularly glib about the threat presented by COVID-19. The culture surrounding the fight game in many senses exaggerates all the right social and sporting ingredients to make the perfect, keep-going-in-the-face-of-a-pandemic stew.

MMA is a space where toughness and overcoming adversity are celebrated above all else. Here the “warrior spirit” even supersedes winning as fighters are praised by fan, commentator, and peer for persevering and absorbing significant damage even if in a losing effort. In MMA gyms, practitioners work to harden the body to make it a more effective tool to inflict damage and withstand attack, all while exchanging tales reinforcing the importance of confidence in the ability to overcome all obstacles. In taking on this challenge, professional, amateur, and hobbyist fighters not only accept the inherent risks of a practice where two competitors seek to render the other unable to fight through a mix of strikes, grappling control, and submission, but also seek out the risk and all it brings with it. In a sense, these are the exact bodies that we do not need to worry about because they are always at risk and always overcoming. And, considering how OK we are watching Tony Ferguson continue to push forward on unsteady legs with a fractured orbital bone, a badly cut face, and a certainly swelling brain during the headlining bout at UFC 249, does a fighter getting COVID-19 really horrify us?

The emphasis on toughness goes hand-in-hand with the overt emphasis on (re)claiming independence and a more traditional brand of masculinity. Which in turn, for a disproportionate number in the MMA gym, goes along with a libertarian or self-described apolitical political orientation. Simultaneously, perhaps due to the meaning-seeking history of martial arts and the demographics of many MMA gyms in the United States and the MMA fan base—often white and often male— conspiracy stories and distrust of the mainstream narrative are common on the mats. If one were seeking out the sport fan-base and athlete pool most likely to have doubts about epidemiological concerns on COVID-19, this would not be a bad place to start.

Guidance, of a sort.

Looking at sport and this event as a model for society is perhaps even more telling. In the case of UFC 249, the most dominant theme, which seemed to underlie all others, was that the sport simply must go on. As our introduction highlighted, even as other sports chose to shutter the doors and wait the storm out, the UFC raced ahead holding an event (sans audience) in Brazil and then setting sails for tribal lands and the mysterious “Fight Island.”

As the UFC continued to push for a live event, it became increasingly more difficult to not see this as a story of company and profit mattering more than the workers who generated the revenue. The UFC began to receive critiques for yet again prioritizing the corporation over fighters who lack financial security, collective bargaining powers, and the ability to turn down fights without fear of future repercussion (see the current lawsuit). This was only made more evident as fighters began to drop off upcoming fight cards due to family responsibilities, mental health concerns, and the inability to train properly with gyms still closed. In addition, before competing, fighters are required to sign away their right to critique the UFCs handling of the event, even in the case of gross negligence.The decisions made during this time have also made it abundantly clear that the rules matter until they don’t. While previously Dana White had voiced frustration with his inability to overturn decisions made by state athletic commissions and directed fan anger towards the government agencies, suddenly the rules no longer applied. If drug testing could not occur in the normal manner, so be it. And, in the most extreme moments of rule skirting, this took the form of proposing that fighters would be taken to the fights without ever knowing the location so that they would be unable to leak the information to regulating bodies.

Finally, Dana White’s historically contentious relationship with the media took on an even more adversarial quality with him questioning their loyalty, their toughness, and their appreciation of the sport. For those seeing a bit of resemblance to the tactics of his friend President Trump, it should come as no surprise that Dana White also followed the very same playbook of simply dismissing criticism as not being true, stating “truths” that defy the evidence at hand, and claiming to be taking health and safety seriously while all the same time failing to deliver with the proper optics.

Other Possible Stories and Lessons

What do we learn from taking this approach to understanding the journey to UFC 249? We conclude with a two final points.

First, the UFC’s recent actions capture the essential qualities of the organization and the larger MMA (if not other major sporting organizations), for better or worse. Some argued that the UFCs efforts to move forward would be a black mark on the sport. However, we suggest that this is the exact move one would expect based on the culture surrounding the sport and the inherent paradoxes that come with the UFCs rapid move from fringe or niche combat sport to mainstream ESPN and Disney subsidiary. The Fight Island proposal bearing more in common with Enter the Dragon or The Running Man than the NFL, and UFC 249 following World Wrestling Entertainment to Florida are not exceptions to MMA’s character but rather reveal the practice’s roots.Second, we hope this essay highlights another key value of sport and key aspect that we are missing during this time. Our critique of the UFC is not that we do not need sport now or that it is a trivial distraction. We both are actually quite sympathetic to claims that we do need sport. However, it is not simply, in this case, the punching and choking that are missed, but rather the text that is provided.

One can imagine an almost identical UFC 249 in terms of fights and production that offered quite a different model. Here emphasis from the very beginning might have been placed on the steps being taken to work with and alongside state commissioners, epidemiologists, and a number of representatives of fighters. Here Dana White would emphasize transparency of decision making, of safety measures, and of process if a fighter does test positive. Here, even if a driving motivation was indeed money to be made and ESPN television contract to fulfill, UFC brass would emphasize the safety of the fighters as the population that matters the most.

From this perspective, the UFCs failure is in offering a story that is simply not the one we need. While the UFC certainly put forth an exciting event, and impressed all watching with their resilience as the rest of the sports world shut down, viewers like ourselves were left to wonder if it would have been better for everyone, much like in the case Tony Ferguson, if they simply threw in the towel.