Let’s face it: after the mid-term elections, many of us are just exhausted by divisive rhetoric—especially on the gun issue. With Michael Bloomberg and the National Rifle Association pouring untold amounts of money into state-level races, the gun debate has been overtaken by the cheap jab, tired cliché, and trite emotional appeal.

But that’s not the kind of debate we have to keep having about guns. There’s an emergent critical mass of sociologists—Harel Shapira, David Yamane, Terressa Benz, and others—who are jump-starting different kinds of conversation. In a recent NYTimes op-ed, Shapira broke ground by unpacking an interesting observation regarding concealed pistol licenses (CPLs): African Americans are disproportionately denied CPLs. But by what mechanism?

To answer that, we have to think about racism in America today. Racism isn’t just about prejudicial attitudes or beliefs. It is also seen in the ways in which laws and social institutions are organized. What appears to be race-neutral—the enforcement of drug laws, test standardization, mortgage applications—still produces racial disparities in criminal justice, education and housing. This isn’t about racist people in these institutions: it’s about how these institutions are set up in the first place.

Gun laws are no different.

First, by federal law, concealed pistol licensing rewards those with a squeaky-clean criminal record. Obviously, this excludes those convicted of violent crimes. But it also excludes people who have been convicted of non-violent crimes—such as drug offenses, for which minorities are disproportionately prosecuted and convicted. We already know from the work of sociologists like Devah Pager that criminal records unduly “mark” African Americans for discrimination, preventing them from rebuilding their lives post-incarceration, through blocked access to housing, education, and job opportunities. Add CPLs to this list.

Perhaps, many will argue, this racial disparity is a small price to pay to keep guns out of convicted criminals’ hands. But it’s not just those with criminal convictions who are barred from obtaining CPLs.

I’ve been attending gun board meetings in a shall-issue state, and I’ve been surprised at what I’ve found

A quick primer: gun board meetings are reserved for CPL applicants who have been denied a CPL or CPL holders with a suspended license. Disproportionately, it is African American men who are called to gun board meetings, but their “crimes” are oftentimes pitifully petty: unpaid parking tickets, tickets for driving with a suspended driver’s license, even decades-old arrests that were never pursued further for one reason or another. In one of the gun boards I am studying, applicants and licensees are called to appear before the board for any police contact. We know from the work of scholars like Chuck Epp, co-author of Pulled Over: How Police Stops Define Race and Citizenship, and extensive New York Times coverage on stop and frisk that African American men experience far more police contact than white men due to investigatory policing, which contributes to their over-representation in the criminal justice system.

The CPL is a context where the racial politics of investigatory policing are compounded: one of the cases I observed involved an African American man in his late 60s or early 70s. He had already had a CPL, but his renewal application was denied. Why? His file was “updated” by out-of-state records, which revealed that he had two arrests from the 1960s from Birmingham, AL, but no convictions. He claimed that the grounds for one of the arrests—drunk driving—was invented by the officer on the scene and he had no recollection of the other arrest. He was ordered to obtain paperwork to prove his claims to the gun board. Unfortunately, the applicant and his wife had already been to Alabama to track down his record, but they couldn’t find the necessary documents. The police claimed they didn’t keep records that far back.This story reveals another way in which the CPL application process disadvantages African Americans: it relies on databases already known to disproportionately feature racial minorities because of their contact with the criminal justice system, as new research from sociologist Sarah Brayne shows. As records are enhanced and cross-tabulated, African Americans are much more likely to “show up in the system” because of a cascade of institutionalized practices that disproportionately target them for surveillance and policing.

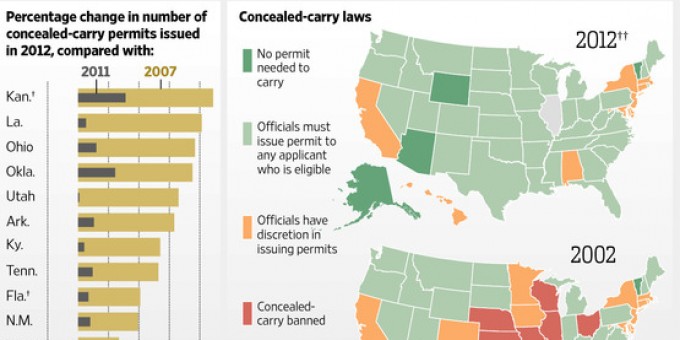

Embracing a Civil Rights discourse, some gun rights advocates have supported the new shall issue concealed pistol licensing system as a way to fix the old, “racist” may issue system put in place in the Southern U.S. during Jim Crow (for one group particularly vocal on this issue, see the Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership at http://jpfo.org). That older, and now generally defunct, system allowed boards a great deal of discretion in determining who was worthy or unworthy of having a firearm.

Just as the may issue system was inflected with the overt, open-faced racial politics of its day, the shall issue system reflects a context of more subtle, institutionalized racism. Today’s system may seem race-neutral, but it reinforces and amplifies racial disparities already endemic to the criminal justice system. The lack of standardization across and within states seems to only exacerbate the problems. There is no federal oversight for CPL issuance, and certainly no organization—neither the NRA, which bills itself as the country’s “oldest Civil Rights organization” nor Michael Bloomberg’s organizations, which advocate “common sense” gun laws—that seems concerned with these disparities.

Comments