Contemporary pollsters often ask us if we trust our government or if we trust people in general. The word trust for many centuries appeared mainly in religious discussions, but as scholars attempted to understand society, trust eventually came to be seen as essential to all levels and sectors of society.

About 125 years ago, Emile Durkheim, principal architect of sociology, helped us understand that modern society hangs together by interdependencies, which he called the collective conscience. Without using the word “trust,” he described how solidarity holds society together with agreements, obligations, laws, moral codes and understandings.

A few years later Durkheim’s nephew, Marcel Mauss, also a noted French sociologist, published The Gift. Drawing upon anthropological studies of gift exchange, he showed how gifts in an almost magical way build social bonds of trust between the giver and receiver. Mauss argued that gift exchange produces solidarity as the identities of the giver and receiver are wrapped up in the object of exchange, which then becomes a symbol of mutual trust.The first sociologist to extensively use the word trust, was Georg Simmel, a German sociologist. He argued that “Without the general trust that people have in each other, society itself would disintegrate.” This claim that society and solidarity depended upon trust first appeared in his 1900 book, ironically titled The Philosophy of Money. Viewed from a sociological perspective, money is a promise or trust that the exchange will be honored.

Since Simmel’s time, thousands of sociological studies have examined the various ways that trust intersects our lives. Most current research related to trust can be readily classified as addressing one of three types of trust: particularized, generalized, or institutional. Particularized trust references small group settings or trust of other persons you can name. Generalized trust refers to trusting people in general. And institutional trust is directed toward specific social institutions, especially one’s government.

Particularized Trust

Particularized trust is reserved for interpersonal relations, especially with those you can name; however, some researchers broaden the term to encompass trust for groups like “close neighbors.” The World Values Study (WVS), which conducts in-person interviews in 51 countries, recently included questions to measure particularized trust. Respondents were asked whether they trust “people they know personally” and whether they trust “their neighbors.” Using these data, researchers found that those with a lot of particularized trust were much more likely to have good physical health as well as other kinds of well-being. Not surprisingly, particularized trust appears to be more powerful than generalized trust in shaping individual behavior.

Generalized Trust

Generalized trust refers to impersonal trust relationships. Many large-scale surveys include one or more questions relating to generalized trust. The most common question is phrased simply as “Do you agree that most people can be trusted?” Variations include “To what extent do you think most people can be trusted?”

Two very large and respected studies in the United States asked about generalized trust in most years between about 1972 and 2018, and both found that Americans lost trust toward “most people” between the early 1970s and the late 2010s. One study was the General Social Survey (GSS) which samples all US adults. And the other study was Monitoring the Future (MTF) of 12th grade students, which is conducted by the University of Michigan. Both the MTF study and the GSS found that generalized trust steadily dropped about 15 points over a 40-year period. It appears very plausible that this drop in generalized trust in the United States was due at least in part to rising wealth inequality. Increasing inequality in wealth leads to inequities in education and health as well as racial disparities.Studies in the US have found that health, happiness and a number of other social factors are linked to generalized trust. International studies have found that trust tends to be higher in countries with high GDP but lower in post-communist ones as well as countries with greater inequality and social and political polarization. In general, the research confirms that trust and quality of life go hand in hand. Each tends to reinforce the other.

Institutional Trust

Institutionalized trust is measured by asking either about trust in institutions or by specific questions like this one from Gallup: “How much confidence do you have in each of the following institutions, a great deal, quite a lot, some or very little?” Gallup reports degrees of confidence for each of nearly 20 different institutions in American society for each year from 1972 to 2019, which you can find here. In 2019 only 4% responded “a great deal” for congress but 45% for the military, the lowest and highest rated institutions respectively.

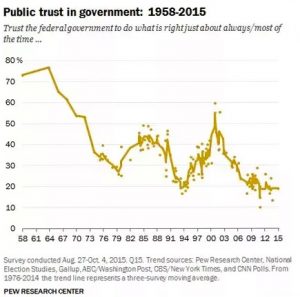

Pew Research harmonized their data with Gallup’s, the National Election Study, and several polling organizations to produce the following chart showing public trust in the Federal Government from 1958 to 2015. This trendline of public trust for the US Government, dropped from 75% to about 20% over a 60-year period, giving a startling portrait of the public’s loss of trust in its national government. It is noteworthy that two of the three periods of decline in public trust in the federal government coincided with the Vietnam War and the Iraq War. Pew Research Center’s brief Beyond Distrust discusses these findings further.

Trust, Happiness and Social Well-being

Unless trust is misplaced, those who feel greater trust in others would be expected to be less fearful and perhaps even feel happier. The 2020 World Happiness Report (WHR) resoundingly confirms that trust leads to happiness or subjective well-being. The 2020 Report utilizes over a million interviews from the Gallup World Poll in over 200 countries. The study also utilized data from the European Social Survey data from 35 countries with almost 400,000 interviews.

The 2020 World Happiness Report (WHR) used several measures of trust: generalized trust; trust in institutions; particularized trust (frequent meetings with friends and relatives or “friends I can count on”); trust in police; and relative absence of corruption, which their report called system trust. Particularized trust statistically increased happiness in every country. The researchers referred to this as a “social environment of trust.” They found trust to be an especially strong predictor of happiness within the happiest 20 countries, which included all the Nordic countries. In reviewing the WHR 2020, the NYTimes examined Finland, the top-ranked country, and concluded that a culture of trust and caring relationships were the secrets of happiness or subjective well-being.

Trust and the Pandemic

In the Spring of 2020, many cities and states began to think about returning to pre-pandemic business as usual. A NY Times reporter gave a report about the confusion and chaos in European countries as restrictions began to loosen. Similar disorganization is evident across the United States because of differences by locale in timing and distancing rules for moving “back to normal.” Opening up shops, travel and schools tends to involve weighing matters of trust even if the word trust is not used. Decision makers tend to ask questions like: Do employees in general trust their employers to keep workspaces safe? Will business owners trust their customers to practice distancing and wear masks? Whereas early-on, informed customers could be trusted, in some places a movement arose to open up the economy early and protesters defied orders to wear masks and maintain social distancing. While polls found a majority of citizens in the US and Europe supported the practice of safe distancing, business owners could no longer trust all of their customers to do so. This erosion of trust from social polarization over safe practices during the pandemic has slowed the return to normalcy.

In Europe, most countries in the northwestern region are “high trust” in that most of the people not only trust one another but trust their government. In contrast, countries in the southeastern regions tend to be “low trust.” Because of the culture of trust in Sweden and Holland, their governments did not impose strict closing rules on businesses during the pandemic, but asked people to practice safe distancing. For three months the spread of the coronavirus in Sweden and Holland was moderate, but in the last week of May, Sweden’s COVID-19 per capita death rate spiked to the highest in the world. Sweden’s government had hoped that the country would reach herd immunity rapidly, but their mistake was not to press hard for “herd distancing” and “herd mask-wearing.” Otherwise, their approach might have worked. In Sweden now, it is too late for trust-based policies because the public has lost faith in their government.Countries in the southeast like Austria and Hungary are “low trust” but their strict and early lockdowns have led to low rates of infection and deaths. The Economist described trust in the European context as a “double-edged sword,” because while trust can be a powerful social force, public policies and science-based practices are necessary as well. The pandemic is not over, so we can continue to observe the role that trust plays in shaping public policies during the pandemic.

The Bigger Picture

In the social sciences today, trust is discussed as an integral part of social cohesion, solidarity, social capital and other forms of social interconnectedness. Yet most of our leaders do not seem to be aware of the power of trust. A century ago Durkheim and Simmel wisely pointed us toward the concepts of solidarity and trust for understanding how society works. Recent decades of social research have given us a much greater understanding of the types of trust and how they each make a difference. We have learned that wealth inequalities, racial disparities and other types of social divisiveness threaten solidarity and trust. Ironically, sociology cannot study trust, or anything else that requires asking people questions, without respondents trusting the researchers.

As the pandemic continues to disrupt society, we will see more clearly how the social forces of trust and solidarity influence peoples’ beliefs, attitudes and social relationships. Probably we will see even more clearly how the erosion and absence of trust leaves us fewer and fewer options. Despite the growth in size and complexity of societies today, trust resides at the center of our understanding of social life. No wonder the notion of trust helps us understand life during the pandemic.

Ron Anderson

June 4, 2020