With the 2026 Winter Olympics in Italy halfway completed, I thought I’d take a few moments to reflect on my thoughts heading into the Games and on what has happened so far. And my focus, to be clear, is not the competitions themselves. Compelling as the drama of victories and defeats may be, my angle is, as always, the social and political issues surrounding the Games.

*****

Heading into the 2026 Winter Olympic Games in Milano Cortina, two main things were on my mind. One was that I was pretty sure American athletes would not be well received by the spectators and journalists who converged upon Italy. Expressions of negativity and hectoring seemed likely because of the outrage provoked by recent American actions on the international stage. This animosity, driven by US threats to take over Greenland by force, lukewarm support for Ukraine in its ongoing war against Russian invasion, and general disregard for NATO and its allies, is particularly pronounced among Europeans, who tend to dominate the Winter Games.

The second matter of my concern was for Olympians from Minnesota, where I live and work. I feared that these athletes—a disproportionately large contingent of American Winter Olympians, something Minnesotans are justifiably proud of—would be asked about the massive immigrant deportation campaign that Immigration and Customs Enforcement has waged in Minnesota, an operation that has not only been deeply unpopular in the state but whose tactics had killed two Minneapolis residents. It seemed almost inevitable to me that Olympians from Minnesota would be asked to comment on ICE activities and the resistance that has been waged in cities and communities across the state. Such interviews and commentaries had the makings of an unenviable, possibly no-win situation for the Olympians—having to choose between their country and their home state, or their principles.

*****

The negative reception from European audiences that I anticipated was unleashed almost immediately during the opening ceremonies. Interestingly, perhaps thankfully, this negativity wasn’t directed against the US delegation but rather against American Vice President J.D. Vance, who was in attendance. Despite IOC directives about decorum, the crowd booed Vance loudly when he appeared on the big screen. Coverage of this reaction was largely edited out of NBC’s original telecast in the United States. But once the news filtered out, American Olympic fans were reminded, especially those who hadn’t been aware otherwise, of the negative standing our country and its leadership now occupy in the international community.

ICE actions quickly came under fire as well, but not in the way I expected. As the Games began, American Olympians spoke, cautiously but courageously, about their concerns about their government and the principles for which they believe it needs to stand.

Jessie Diggins, a cross-country skier from Afton, Minnesota (and among the most decorated Winter Olympians in US history), was one of the first: “I’m racing for an American people who stand for love, for acceptance, for compassion, honesty, and respect for others.” In the early days of the Olympiad, other American athletes made similar statements: speedskater Connor McDermott-Mostowy, freestyle skiers Hunter Hess and Chris Littis, figure skater Amber Glenn, and alpine skier Mikaela Shiffrin. As Minnesota curler Rich Ruohonen, who works as a personal injury lawyer in the Twin Cities, put it: “What’s happening in Minnesota is wrong. There’s no gray area.”

Such statements, predictably, angered American conservatives, and some athletes found themselves the subject of harsh online attacks (including threats to physical safety). Vance himself led the charge: “You’re not there to pop off about politics.” But Olympians such as Chloe Kim spoke up for teammates who were attacked and for the most part the sentiments have been received as principled and restrained—resonant with the messages of peace, tolerance, and human rights conveyed during the Opening Ceremonies.

*****

Less well-received, at least by Olympic authorities, was Ukrainian skeleton racer Vladyslav Heraskevych’s helmet featuring images of fellow Ukrainian athletes who had been killed in Russia’s invasion of his home nation. After a reported eight-hour hearing, the International Olympic Committee ruled that Heraskevych would not be allowed to compete on the grounds that his helmet violated the athlete expression guidelines as defined under “Rule 50” of the Olympic Charter.

It is a fundamental principle that sport at the Olympic Games is neutral and must be separate from political, religious and any other type of interference. The focus … must remain on athletes’ performance, sport and the harmony that the Games seek to advance.

The verdict, delivered in person by a tearful IOC President Kirsty Coventry, was troubling on multiple grounds. One is that the IOC itself has not allowed an official Russian delegation to participate in the Games and barred Russian athletes from competing under their national flag. Even so, some Russian athletes allowed to compete as “neutrals” made no secret of their support for Putin and the military invasion, and there are reports that Italian snowboarder Roland Fischnaller displayed a Russian flag on his helmet.

*****

All this highlights the powerful, if often misunderstood, social and political significance of the Olympics—impacts that result directly from the global scope of the Games and their reliance on nationalism as a mode of organizing (and thus heightening the emotional intensity of) the ceremonies and competitions.

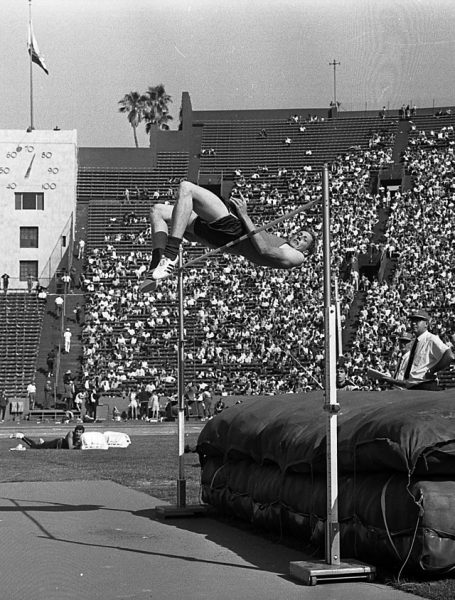

Let me conclude by talking about an Olympian’s story from the 1968 Games that I think is relevant and resonant again. For a change, this story is not about Tommie Smith and John Carlos and their iconic clenched fist salute on the victory stand. It is, rather, about Dick Fosbury, the American who won gold in Mexico City (and revolutionized the high jump) by leaping over the bar backwards—the now universal technique known as the “Fosbury Flop.”

The story comes from an interview with Fosbury conducted by the American Olympic anthropologist John MacAloon over a decade after Fosbury’s victory. When MacAloon asked about how Fosbury felt receiving his medal, the high jumper recalled feeling patriotic, but also that he “didn’t need the victory ceremony at all,” had not appreciated being “put on a pedestal,” and didn’t want to be a “role model” or “hero.”

Being a college student at the time, I was against everything the government was doing as far as Viet Nam and as far as resisting any kind of protest the people were doing legitimately. So I was really against the United States government and so I really felt kind of anti-patriotic.

However, Fosbury then went on to describe the “overwhelming feelings” he got caught up in on the victory stand itself. Fosbury recalled it as “pretty confusing.” “I couldn’t believe what was happening. I guess it didn’t make sense to me.”

Years later, Fosbury was still struggling to account for the powerful and conflicting emotions he experienced on the victory stand. “Maybe I did feel proud to be an American and to be from Oregon and proud to be representing my friends and different people from my hometown, but at the same time I didn’t respect the government.”

Such are the tensions or even contradictions of the collective identities and social issues played out on the Olympic stage. What does it mean to compete for your nation when you don’t agree with the actions of its government? Or, to participate in a movement that purports to stand for peace, but also wants to stay neutral even in the face of ongoing violence, including the killing of Olympians?

The Olympics don’t directly impact politics or bring about direct social change. But they can and often do—if we are watching seriously—call attention to what is happening in the world. And this attention, this platform, can be used to underscore and amplify causes as well.

On this point, I daresay that the Olympic ban handed to Heraskevych has given more prominence to the ongoing war and terrors in Ukraine in the United States and around the world than it likely would have gotten otherwise. That victory may be worth more than any medal Heraskevych might have won had he been allowed to compete.

As the final week of competition plays out, I will be watching to see if other Olympians—especially Americans, and perhaps even those from Minnesota—feel compelled to speak out on social issues and how such messages will be received.