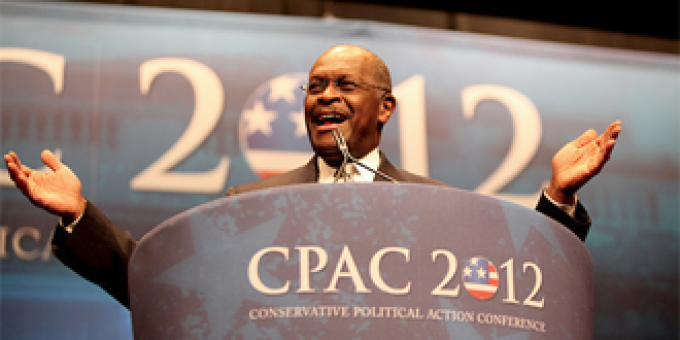

Republican Presidential Candidate Herman Cain and the Utility of Blackness for the Political Right

In November of last year, Herman Cain was the front-runner for the Republican presidential nomination, embroiled in a sexual harassment scandal, and the darling of the Tea Party. There were widespread claims at that time that Cain’s candidacy “proved” the far right was not racist. Like the 2007-2008 arguments that Barack Obama’s ascent “proved” that the U.S. was now a “colorblind” nation, this claim was false and misleading.

In my 2011 book, “At This Defining Moment”: Barack Obama’s Presidential Candidacy and the New Politics of Race, I focused on contemporary racial politics among those on the left of the political spectrum. The Cain phenomenon, however, allows for an exploration of the emergent dimensions of the racial politics of the right—in particular, the political utility of blackness for conservatives in the present age.

To contextualize the issues raised by Cain’s campaign, it is useful to first consider how race played out for Obama in 2007-2008. I argue that Obama did not run a “raceless” presidential campaign, he did not “transcend” race, and he was elected not in spite of his race, but in significant measure because of it.In fact, race was used as a sort of oppositional frame. Obama was highly praised for the degree to which he was not a “traditional” black public figure, like Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, or other blacks with whom the wider (white) public had grown increasingly impatient. The candidate also won major points among for his willingness to repudiate the supposed lifestyles and choices of the black poor. Consider his repeated calls for “Cousin Ray Ray,” “Uncle Pookie,” and other mythical poor black men to “get up off the couch,” “pull up their pants,” and take “personal responsibility” for their own lives.

As a post-racial black candidate, Obama was believed through his magical blackness to be able to reconcile Americans of all colors and creeds, grant whites absolution for the racial sins of the past, and redeem the nation by demonstrating the U.S. to be again a place of open opportunity and tolerance. Obama was affable, charismatic, non-confrontational, and highly articulate. In him, the pundits claimed, there was a man who would take the country beyond the “stale and tired” racial politics of the past. Firmly “rooted” in the black community, Obama was nevertheless not “limited to it” or “defined by it.” Thus, we heard again and again, his ascent heralded the dawn of a “new politics of race.”

In the 2012 presidential race, we are faced with a new set of questions raised by the candidacy of Herman Cain. In his run, race played out in some ways quite differently than it did for Obama, but there were striking parallels as well. What explains Cain’s popularity on the right, and how was it tied to his race? When, and in what ways, did Cain seek to use race to his advantage (say, by reminding supporters of his blackness or claiming to be a victim of liberal racism), and when did he seek to deemphasize it? What did Cain’s staunch support among Tea Party-types tell us about the racial politics of the most conservative Americans?

As we watched the campaign unfold, the answers to these questions were never entirely clear—in part because Herman Cain had been on the national radar for a relatively short time, and in part because his campaign underwent a number of surprising twists and turns in its brief existence.

The first of these was how Cain rocketed to the front of the GOP presidential pack, seemingly out of nowhere. We first heard of Herman Cain in the weeks following the Iowa straw poll, when many assumed that the field of serious contenders for the Republican presidential nomination had been largely established. But the former Godfather’s Pizza CEO soon eclipsed the presumptive nominee, former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, and remained at the top of the polls for weeks.

The second major development in Cain’s story was the emergence of reports of a series of unwelcome sexual advances the candidate allegedly made toward female employees as head of the National Restaurant Association. As with the first arc of his candidacy, the sexual assault scandal took on highly racialized dimensions: those on the right claimed that Cain had either been subject to a “high-tech lynching” by the liberal media or that the “democrat machine” was trying to take him down. There was also the glaring, but largely unremarked upon fact that all of the women who claimed Cain had sexually harassed them were white—blond, at that.

Cain managed to survive the scandal for several weeks. He vigorously denied the charges levied against him in unequivocal statements such as “No, there was no kind of settlement ever,” “I have never met that woman in my life,” and “I have never done anything inappropriate to anyone, ever, period!” As information contradicting Cain’s statements began to materialize, the candidate lost both credibility and viability in the eyes of many political observers. But Cain’s hard-core supporters rose to his defense, pouring money into his campaign coffers and booing moderators who raised questions about the harassment charges at the GOP presidential debate in Michigan.

You may remember that Cain eventually bowed out of the race, after an Atlanta woman named Ginger White came forward alleging that the two of them had had a 13-year affair. Though Cain vigorously denied it, his brief, wacky, and somewhat farcical run for the White House was over. Still, it merits serious consideration, as related to the issues of race, blackness, and conservative electoral politics.

In an interview I did with a local television news station in October of last year, I was asked whether I thought Cain could win a significant proportion of the black vote. (Cain had claimed that at least a third of all black voters would turn out for him). This question struck me as odd; it was clear then that Cain wasn’t even seriously trying to court black voters. Many of the statements Cain made about blacks were insulting and belittling. He described African Americans as “brainwashed” by the Democratic party, living on the “democratic plantation.” He implied that black voters lacked political intelligence and were unable to think for themselves. In one televised speech, Cain even said that since he had fully achieved the American dream, there was nothing (for African Americans) “to complain about!”Other non-whites and non-Christians were dismissed as quickly. Candidate Cain stated in March of last year that, if he were to become president, he would not appoint a Muslim to his cabinet or to a federal judgeship. As he told the magazine Christianity Today, “[B]ased upon the little knowledge that I have of the Muslim religion, you know, they have an objective to convert all infidels or kill them.” In October 2011, riding high in the polls, he called for an electrified, 20-foot fence along the U.S. border with Mexico, surrounded by signs declaring in English and in Spanish “It will kill you.” The same month, in an interview with a conservative talk radio station, Cain said many blacks on the left were more racist than the white conservatives they complained about—a claim that strongly echoes the frequent complaints of “reverse racism” we hear from the right.

Overall, therefore, it appears Herman Cain’s chief utility for the right was to attack or further delegitimize the collective interests of blacks and other nonwhites in the 21st century. In a way, Cain’s candidacy was a kind of preparatory response to the coming demographic tidal wave. By the year 2050, whites will slip to less than half of the population for the first time in the nation’s history, and the U.S. will become a “majority-minority” nation. But Cain’s candidacy represented a very partial and cynical response to this change. Rather than representing an honest attempt to make conservativism a more diverse and inclusive political movement, it came across as a pushback; part of a larger, Tea Party-led attempt to keep power, wealth, and national identity in the control of whites, even as they lose grasp of the reins.

I concede that black conservativism is potentially a legitimate strain of black political thought. But the face of black conservatism we see most often today is not about or for black people, but about and for whites (consider for example Larry Elder, Alan Keyes, Allan West, Michael Steele, Walter Williams, Juan Williams, and Artur Davis, to name a few) I suggest that much of Herman Cain’s appeal stemmed from the fact that he was willing to speak the kinds of “truths” about race that whites on the far right are clamoring to hear in an age in which they feel imperiled. It also explains polemical right-winger Ann Coulter’s declaration “our blacks are better than theirs.”

It is crucial to point out, however, that Barack Obama performed the same function for white Democrats in 2007-2008. During his campaign, candidate Obama spoke the “truths” about race that white liberals most wanted to hear: that they were good and noble people, that they were absolved of the sins of the past, that racism in the U.S. was largely vanquished, and that Jackson, Sharpton, and poor blacks as a whole were in fact highly problematic people.

Some of the racial “truths,” then, that Cain spoke during his run were quite similar to those spoken by Obama, just put more bluntly. Cain, too, stood against “quota style” affirmative action, called for black personal responsibility (“What’s there to complain about?” “If you don’t have a job, it’s your fault,” etc.), and, with his “brainwashed” statement, questioned the common sense, judgment, and worldview of most black Americans. This rhetorical tie is no mere coincidence. As I argue in my book, the convergence between conservative and liberal stances on racial matters is an indication of the degree to which American racial politics as a whole have shifted to the right in the last several decades. As a number of scholars of race have written, where affirmative action, welfare rights, school desegregation, and the enforcement of anti-discrimination law were once cornerstones of liberalism, such initiatives are now only meekly defended, if at all.

It is also important to consider Cain’s “performance of blackness.” I claim in my book that Obama’s bounded, depoliticized performances of blackness (affectionate fist-bumps with Michelle, demonstrated serious basketball habit, ability to slip in and out of “black” forms of speech, and occasional references to elements of hip-hop culture) were highly appealing to many whites, as it seemed that they might serve as the basis for a revitalized, newly authentic American national identity.

Cain’s “performances” of blackness, however, were somewhat different. He said that if he were the “flavor of the month” he must be “black walnut,” joked that his Secret Service code name should be “Cornbread,” and began the speech in which he officially declared his candidacy in front of a nearly all-white, majority Tea Party audience by saying, “Aww, shucky ducky now.” A number of writers have characterized this as a kind of “minstrelsy,” describing Cain in these episodes as self-deprecating, bowing and stooping before whites. The most wellknown example came from the journalist Touré, who literally referred to Cain as a minstrel in an article in Time magazine, then later on MSNBC.

While I think there is something to this reading, the idea that he merely made himself a racial “act” doesn’t seem fully logical to me. Cain is extraordinarily self-confident, often bordering on arrogant (after all, he refers to himself in the third person). His Tea-Party base was looking to him not as a sidekick but as the leader of the nation. Instead, Cain seemed to be saying that it is not necessary to take black people or blackness itself seriously. He demonstrated that it was okay, or even humorous, for conservatives to articulate age-old stereotypes about blacks or even to make references to slavery (e.g., “the democratic political plantation”) to defend their points of view against those of prominent blacks and liberals in general.Defending Herman Cain was, in part, a means of crying “reverse racism” out loud. It was also an attempt to forcefully deny that the conservative movement remains a white, old boys’ club in which people (i.e., men) of color might occasionally function as charming adornments. Cain’s staunchest supporters were found among those who sought to “take America back”—back from Barack Obama, back from “socialism,” back from secular liberalism, gays and lesbians, the Occupy Wall Street movement, and outspoken, progressive leaders of color—in short, back to the good old days when white hegemony was absolute, since today it is in inevitable decline.

Comments 2

Nikki — October 14, 2012

I enjoyed this. Herman Cain received a lot of attention and seems to be a remarkable figure worth analyzing but I have been seen little in depth discussion of his significance.

I do wish there was further explanation of the section where Professor Logan states that "There was also the glaring, but largely unremarked upon fact that all of the women who claimed Cain had sexually harassed them were white—blonde, at that". What are we supposed to make of this? It does fit racial stereotypes and the accusations have historical precedence. Does that mean we dismiss the charges or what?

I am also curious what Professor Logan would make of Cain's post-candidacy friendship with Stephen Colbert (appearing at rallies and embracing his Pokemon fame) and not being allowed to speak at the republican convention?

Alfred Duckett — February 12, 2017

Great article - insightful indeed. Many of the same factoids surround the Trump campaign and canada you, yet the results, as we all know, was vastly different. Racism is strong and getting stronger!