As media gasp at the enormous viewership of the most recent Invisible Children video and the public engages in a heated debate over the organization’s financial practices and the apparent breakdown of one of its founders, one group has been seemingly overlooked: Ugandans. Amy Finnegan, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota-Rochester, however, wrote her dissertation on social movements and activism, with a particular focus on the interaction—or lack thereof —between Invisible Children and indigenous activist groups in northern Uganda. The Society Pages reached out to Finnegan to learn more about how this movement is framed, the reaction of Ugandan activists, and how this model of involvement might actually be detrimental to the young people who join the campaign. To listen to the entirety of this conversation, check out the podcast over on Office Hours or, for teaching ideas, check out Teaching TSP.

Shannon Golden: Dr. Finnegan, we’re so pleased to speak with you. Could you please tell us how you came to be involved with Uganda?

Amy Finnegan: Well, I have been going to Uganda since 2000. I started out in a volunteer capacity when I finished university, and over the years I came to focus on northern Uganda and Gulu, specifically. I’ve worked for a local human rights organization there, I’ve worked for a large, international HIV/AIDS project, and I’ve conducted research and taught at the University in Gulu. In 2000, I was really struck with the gravity of what war and what violence does to people’s lives. That compelled me to go home and learn more about conflict and violence, and it compelled me to continue to find ways to return to Uganda.

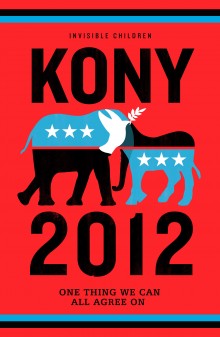

SG: So, you’ve had a dozen now of engagement with the people who have experienced this war and who are now rebuilding their lives in Uganda. What was your initial reaction to the KONY2012 campaign by Invisible Children?

AF:I’ve been studying Invisible Children more seriously for about three years, but I had been aware of them and their existence since their very first video in 2005. And I think my reaction to KONY2012 was probably similar to my reaction to the very first video I saw—honestly, it’s a real mix of ambivalence. I remember how, at first, I was inspired and psyched and moved by what other young people were trying to do to galvanize attention, to raise awareness, raise consciousness about a really serious and grave situation that, until about 2003, had gotten really minimal international attention. But I also remember feeling a sense of dissonance right away with the way the story was being told and what I had personally experienced, seen, and read about through my own experience in Uganda.

My dissertation, “Beyond Victimhood: Narratives of Social Change from and for Northern Uganda,” was really born from that dissonance. It’s a qualitative piece, based on ethnography, interviews, and focus groups I conducted both in northern Uganda and in the United States. I focused on Invisible Children as an activist group in the United States and also followed Ugandan indigenous activist groups involved in peace and human rights. I took a kind of participatory-action stance in my work, and I did a lot of reflection on my own journey from a model of activism that I think was probably in line with what Invisible Children is about to a more critical model which is, hopefully, much more in the values of solidarity.

So, with that participatory-research-action stance, what I did was ask Ugandans to reflect on Invisible Children, watch some of the films together, and discuss things like, “What does this say?” and “How do you feel about what it says?” and “How does it reflect on your reality and what you think is necessary at this point?” With the young Americans, I also tried to start a conversation about how they relate to Ugandan activists and how they could, perhaps, be more in dialog with them. So, one of my central arguments is that a lot of the Invisible Children rhetoric is very much continuing a neocolonial story around Africa as a place primarily of victims that sort of implores Western intervention. It’s obviously much more than that; in fact, that victimhood, I think, is very patronizing and ineffective in terms of how it addresses the issues in northern Uganda.

In one chapter, I talk particularly about framing. Invisible Children has a sort of “poor victims” frame, while the indigenous activism (or the Uganda-originated activism) frame was more “victims preventing the next generation of victims.” So it’s not that I don’t think the Ugandans also use the language of victimhood, because I think that they do, but there’s much more of a sense of agency in the way that they talk about being victims. I think that points to some of the work that Francesca Poletta and others have done about how who does the naming of victimhood really matters. If you’re calling yourself a victim and using that as kind of a base for action, empowerment, agency, decision making, and a platform for further action, I think that’s a very different thing than having others name a large group of people “victims”—particularly others coming from, you know, a very powerful country, others that are primarily white naming a largely black, poor population as victims. The way that naming process happens is pretty different and really changes the power of that word “victim.”

SG: This touches on something that’s very key to sociological understanding: names become important when you consider the power differentials and dynamics behind them.

AF: The way that things in Uganda are being framed does a couple things. It really does a disservice to young Americans who are at a critical point in their lives where they’re learning about the world and becoming mobilized to see themselves as agents. Invisible Children’s kind of short-sighted version of what Africa is, in

terms of being largely comprised of victims, really teaches Americans in a narrow way. It teaches them a narrow understanding of Africa, but it also teaches them a narrow way about their possible platforms for engaging in or working for social change. Invisible Children emphasizes fundraising, in the beginning, as one of the only things, one of the only actions that these young people can take. And so I think it really narrows how young Americans understand Africa and their role in engaging Africa’s problems. In Uganda, I find Invisible Children’s impact is sort of marginal, so I think that disservice around victimhood probably does a greater disservice to the young Americans. I do make an argument in my dissertation that, ultimately, there wasn’t a huge backlash of Ugandans against Invisible Children, and I was really surprised by that, because, coming from sort of a post-colonial perspective, I remember watching the films and being outraged! Like, “How can you tell a story about Africa in such a narrow way and not really take into account the complexity of the situation?” I think ultimately, it’s because they don’t matter that much either way in Ugandans’ lives. They do some good things, they do some bad things, but their impact is quite small in northern Uganda. I think in Uganda it’s like, life’s going on and, “Oh, you want to do something on our behalf? Okay… You know, it won’t make things worse for us. That’s okay.”

SG: So, you expected Ugandans to be more outraged by the way that the story was presented by Invisible Children—do you think it’s because people in northern Uganda aren’t hearing that story, that narrative, that they’re putting out?

AF: I think that’s part of it, for sure. When I was showing the films, many Ugandans hadn’t seen them before. But that’s where I go back to this real dissonance. Life goes on in Uganda, and, particularly goes on in terms of moving forward thanks to the work of Ugandan activists and Ugandan groups that do the best they can to try to address the situation of war and human rights. And so, it’s not like people are waiting around for Invisible Children to come and like fix their situation, which is the story I think that’s being told in America. And so I think young Americans, then, really come away with a sort of self-indulgent, self-absorbed kind of perspective on what their role is in northern Uganda. And while I think it’s good to mobilize young people, I don’t think that it’s appropriate to tell them they’re playing a more important role than they actually are.

SG: That sense of individual agency among young people in the U.S. can be inspiring, right, and can be important—you want people to feel empowered—but at the same time, it can’t discount the people who already are working on these issues and have been for a long time.

AF: Right, exactly. Invisible Children’s activism can really drown out indigenous voices in a way that I think actually can have a really significant impact on the ground. Because, arguably, those local voices and initiatives are grounded in much more context and much more breadth of history and understanding of the actors—they’ve lived it themselves for the last 20-plus years. So, if we’re drowning out those voices because we’re listening to a flashy social media campaign put out by westerners, I think we’re all worse off for it.

SG: Invisible Children’s entire campaign is framed as “now or never”—basically, that this year has some key, pivotal role to play in ending this conflict. Do you see it that way?

AF:That’s a great question! I think most people involved in the debate want the same thing, which is for the war to end as quickly as possible with as few casualties as possible, while addressing some of the underlying issues. I don’t necessarily think that 2012 is a “special moment,” But

I think Invisible Children needs to continue to create media and a sense of urgency about what they’re trying to do—I mean, all activists try to do that. We can’t say, “Oh, you know, this could happen any time.” You need to put some pressure on it, and I think Invisible Children’s done that very well by saying this expires on December 31st, 2012. But in terms of sort of in the broader historical context, no, I don’t necessarily think that there’s any particularly salient moment that 2012 offers in this conflict.

In the end, I feel a lot of ambivalence around this, and I’ve been struck by the volume of critique about Invisible Children. It’s been sort of heartening to see people critically thinking through this situation and the appropriate ways to engage—by both Ugandans and outsiders. So that’s been exciting. But we academics can offer more beyond just critiquing KONY2012. We really need to focus on thinking about engaging these millions of people who have now seen the YouTube video and are fired up and disturbed that there is a situation such as there is with Joseph Kony and there are kids and adults who have been affected by war in other parts of the world that they didn’t even know about… how do we engage them and shift their orientation from this sort of “rescue” mentality to one that’s really based in social justice and based in solidarity?

It’s possible, but it’s a difficult task. Teachers have an important role to play in our classrooms in trying to engage people so that they can feel that fire of mobilization but in a way that involves strategic critical thinking. A lot of people have written things like, “Oh, but these people have good intentions!” And I actually do believe that they have good intentions—that Invisible Children is not just this selfish, misinformed, neocolonialist group—but I don’t think that’s enough. Just because we have good intentions and we want to do something isn’t enough. I mean, if we really want to be effective social movement activists, it’s going to require a lot more than intentions: it’s going to require preparations, research, learning, thinking through strategies and mobilization, evaluation… So I don’t think we should just dismiss Invisible Children and other groups as misinformed, social media, celebrity-following people, but think of them as people who could play a role in social justice.

Comments