This May marks the 25th anniversary of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. The United States looks much different than it did 25 years ago, as does its Asian American population.

Asian Americans are now the fastest growing racial group in the country, with immigrants from South Asia fueling much of that growth. Indeed, Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, and Indians have nearly doubled their share of the Asian American population, from 14 percent in 1990 to 26 percent today. Just as important, South Asians have been prominently featured in news coverage of Asian immigrants, from success stories like the rise of Indian American CEOs like Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, to heartbreaking stories of hate crimes and murders in the post-9/11 era.

In 1992, news headlines of Asian Americans focused on Korean grocers being robbed in poor, inner-city neighborhoods like Harlem, West Philadelphia, and East Los Angeles. These have been replaced with headlines of Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims being shot, beaten, and killed across the country. Between November 2015 and November 2016, the nonprofit group South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT) documented 140 acts of hate violence, matching levels found in the year following the September 11, 2001 attacks.

More recently, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, a 33 year-old Indian engineer, was shot and killed in Kansas City by a white man who yelled at Kuchibhotla to “Get out of my country!” In February 2015, Sureshbhai Patel, a 57-year-old Indian grandfather in Alabama, was beaten so severely by two police officers that he needed spinal fusion surgery to repair damage to his back.

As we celebrate APAHM, we ask whether these fundamental shifts in the Asian American experience are reflected in our understanding of who is Asian American. As scholars of immigration and race, our reading of the selective outrage by Asian American groups over the killings of South Asians suggests that this is not the case.

For example, while South Asian organizations have been vocal in their denunciation of these incidents and calls for greater accountability, pan-Asian voices seem to be far less muted today than they were in 1983 after the murder of Vincent Chin, or in 1992 after the Los Angeles uprising. Perhaps just as damning, The New York Times invited readers in November 2016 to participate in a video project on discrimination against Asian Americans, but failed to include any South Asian voices among nearly two dozen perspectives.

There is plenty of suggestive evidence, then, that South Asians in the United States are marginalized in the common public understanding of who counts as Asian American. In the 2016 National Asian American Survey, we sought a more systematic way to answer this question. In the survey, we randomly read a list of different groups (Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Indian, Filipino, Pakistani, and Arabs or Middle Eastern people), and asked our respondents: “Tell me if you think the group is very likely to be Asian or Asian American, somewhat likely, or not likely to be Asian or Asian American.”

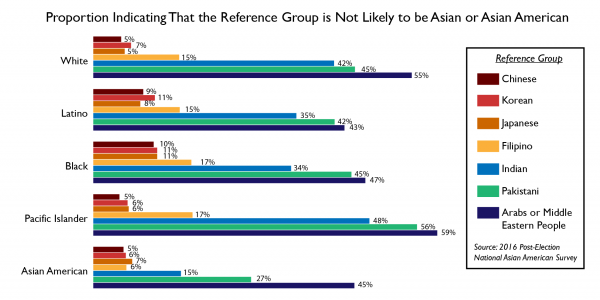

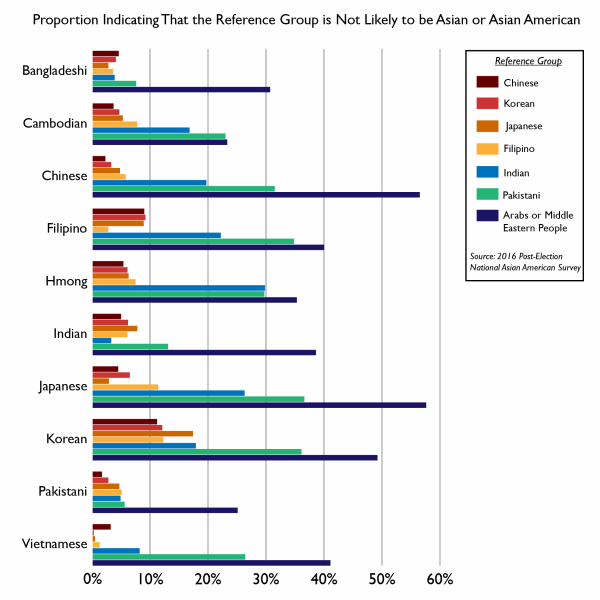

Some of the survey results were unsurprising. Most Whites, Blacks, and Latinos agreed that Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans are Asian or Asian American. Only about 5% of Whites reported that Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans are not likely to be Asian or Asian American, and among Blacks and Latinos, the figure was about 10 percent. The Asian ethnic groups in our survey—Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, Vietnamese, Koreans, Japanese, Cambodian, Laotian, Hmong, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders—felt similarly: only a small proportion thought that Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans are not likely to be Asian or Asian American.

Stark differences emerged, however, when we asked about Indians and Pakistanis. Among Whites, 41% reported that Indians are not likely to be Asian, and for Pakistanis, the figure is even higher at 45 percent. While Blacks and Latinos were more likely to see Indians as Asian (35%), they were just as likely as Whites to see Pakistanis as not Asian. Most jarring is that other Asian Americans were just as likely to perceive Indians and Pakistanis as not Asian, despite the fact that Indians and Pakistanis see themselves as Asian. Perceptions about Filipinos fall in between, and they, too, see themselves as Asian.

What our survey data reveal is that Americans—including Asian Americans—draw a sharp boundary between Asian and non-Asian that separates East Asians (Chinese, Korean, and Japanese) from South Asians (Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis) and, to a lesser extent, Southeast Asians like Filipinos.

What our survey data reveal is that Americans—including Asian Americans—draw a sharp boundary between Asian and non-Asian that separates East Asians (Chinese, Korean, and Japanese) from South Asians (Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis) and, to a lesser extent, Southeast Asians like Filipinos.

Hence, there is a cultural lag between the demographic realities of today’s Asian American population, and the cultural perception of who counts as Asian American. Moreover, rather than expanding the boundary around the category to include newer South Asian groups, Americans—including many Asian Americans—exclude them from the fold.

Why is this important? When we perceive only some ethnic groups as Asian American and exclude others, we see and hear only selective narratives. This selectivity affects our understanding of anti-Asian prejudice and discrimination. Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, Filipinos, and Indians may all be targets of racist and nativist assumptions, including questions about where are you really from, remarks about our unaccented English, and taunts to “Go back to your country!” Both of us can attest to this.

But one of us is much more likely to be stopped for random security checks at airports, detained as we re-enter the country, perceived as a terrorist, and be the victim of hate crimes. These forms of anti-Asian discrimination have become more numerous after 9/11, and more acute after Trump’s proposed Muslim ban.

Yes, we are different genders, but that is less significant than our perceived racial differences. To fail to see Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis as Asian—especially when they see themselves as such—is to silence their voices. It also risks promoting an incomplete portrait of Asian Americans that ignores more threatening, dangerous, and even deadly forms of anti-Asian discrimination.

When Srinivas Kuchibhotla was murdered and Sureshbhai Patel was beaten by two police officers, not all Asian Americans identified with them. Rather than drawing internal boundaries, we should embrace our diversity and redouble our commitment to racial justice.

Recommended Readings

Richard Alba. 2005. “Bright vs. Blurred Boundaries: Second-generation Assimilation and Exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28: 20-49.

Michèle Lamont and Virág Molnár. 2002. “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167-195.

Dina G. Okamoto. 2014. Redefining Race: Asian American Panethnicity and Shifting Ethnic Boundaries. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Michael Omi and Howard Winant. 1994. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge.

Lavina Dhingra Shankar and Rajini Srikanth, Eds. 1998. A Part, Yet Apart. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Andreas Wimmer. 2008. “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 113: 970–1022.

This article was adapted from “In the Outrage Over Discrimination, How Do We Define ‘Asian American’?” by Jennifer Lee and Karthick Ramakrishnan, NBC News, May 16, 2017.