Companies donate to political campaigns in order to gain some leverage over policy making processes. This fun interactive graphic (via) allows you to see which companies donate primarily to Republican and Democratic campaigns, and which straddle the political fence. These are the companies with the largest total contribution:

The most Republican leaning:

The most Democratic leaning:

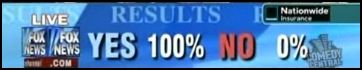

You can also search by type of company. For example, media and entertainment:

Transportation:

Pharmaceuticals:

UPDATE: Comments on this thread have been closed.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.