Every spring, my daughter receives an invitation to participate in a local Girls on the Run (GOTR) program. Every spring, I hesitate saying, “yes.”

Girls on the Run (GOTR) is a non-profit organization with about 200 councils across the U.S. and Canada. Over 10 to 12 weeks, councils help organize teams of girls in 3rd through 8th grades to train for and complete a 5K run.

Volunteer coaches lead their team through the program’s pre-packaged curriculum, consisting of lessons that “encourage positive emotional, social, mental and physical development.” Among other things they discuss self-esteem, confidence, team work, healthy relationships, and “challenges girls face.” Boys are not allowed to participate in the program. The 5K is described by GOTR as the ending “moment in time that beautifully reflects the very essence of the program goals.”

The starting line has the atmosphere of a party. Music is played over loud speakers, pumping teen pop (with lyrics laden with sexual innuendo and “crushes” on boys) and oldies that carry an affirmative “you can do it” message like Gaynor’s, “I Will Survive.”

Vendors (local businesses and organizations) bring tables to engage the girls and their parents in products/services they have available. This is not the only form of capitalistic opportunism affiliated with GOTR. The international organization’s official sponsors include Lego Friends – a line of Legos that emphasize single-sexed socialization (not building!) and Secret’s campaign “Mean Stinks” (featuring another pop glam star, Demi Lovato) that emphasizes painting fingernails blue, among other frivolous things, to address girl-on-girl bullying.

The run is an odd scene. Though boys have been banned from participation, older male relatives, friends, and teachers are encouraged to run with girls as their sponsors. It has become a unique trademark of GOTR that these men, and many of the women and girls, dress “hyper-feminine” (e.g., in skirts, tutus, big bows, bold patterned knee-high socks, tiaras, etc.), apply make-up or face paint, and spray color their hair. The idea is to “girl it up.”

Over the years, I’ve become increasingly uncomfortable with this event for a couple of reasons.

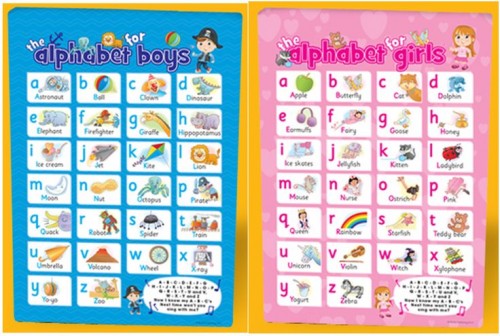

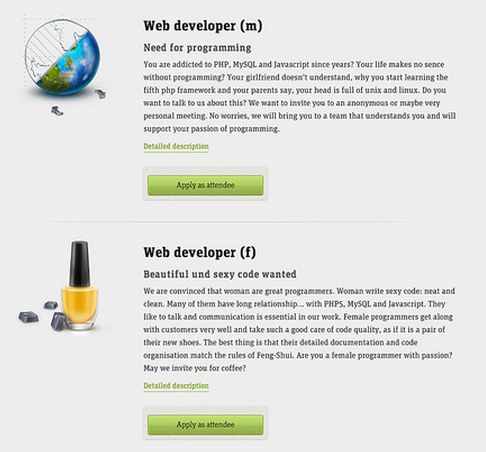

First, encouraging girls to “girl it up”—or I prefer, “glam it up,” so that we don’t appropriate these behaviors just for girls—can be fun, an opportunity to step out and beyond what is practiced in everyday life. But there’s no corresponding encouragement to “butch it up” if they desire, or do some combination of both. In the end, then, this simply serves to reproduce gender stereotypes and the old-fashioned and false notion that gender is binary.

Second, by bombarding girls with “positive” messages about themselves meant to counteract negative ones, the program implicitly gives credence to the idea that girls aren’t considered equal to boys. What messages are girls really getting when special programs are aimed at trying to make them feel good about themselves as girls?

Although I have always given in to my daughter’s requests, at some point I am going to say “no.” Instead of reinforcing the box she’s put into, and decorating it with a pretty bow, we’ll have to start unpacking mainstream girl culture together.

Scott Richardson is an assistant professor of educational foundations and affiliate of women’s studies at Millersville University of Pennsylvania. You can follow him on Twitter.