Cross-posted at the Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, and BlogHer.

In an Op-Ed article on hookup culture in college, Bob Laird links binge drinking and casual sex to sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancies, confusion, low self-esteem, unhappiness, vomiting, ethical retardation, low grades and emotional inadequacy. “How nice of The Times to include this leftover piece from 1957 today,” snarked a reader in the online comments.

Fair enough, but Laird is more than out of touch. He also fundamentally misunderstands hookup culture, the relationships that form within it and the real source of the problems arising from some sexual relationships.

Laird makes the common mistake of assuming that casual sex is rampant on college campuses. It’s true that more than 90% of students say that their campus is characterized by a hookup culture. But in fact, no more than 20% of students hook up very often; one-third of them abstain from hooking up altogether, and the remainder are occasional participators.

If you do the math, this is what you get: The median number of college hookups for a graduating senior is seven. This includes instances in which there was intercourse, but also times when two people just made out with their clothes on. The typical student acquires only two new sexual partners during college. Half of all hookups are with someone the person has hooked up with before. A quarter of students will be virgins when they graduate.

In other words, there’s no bacchanalian orgy on college campuses, so we can stop wringing our hands about that.

Laird argues that students aren’t interested in and won’t form relationships if “they are simply focused on the next hookup.” Wrong. The majority of students — 70% of women and 73% of men —report that they’d like to have a committed relationship, and 95% of women and 77% of men prefer dating to hooking up. In fact, about three-quarters of students will enter a long-term monogamous relationship while in college.

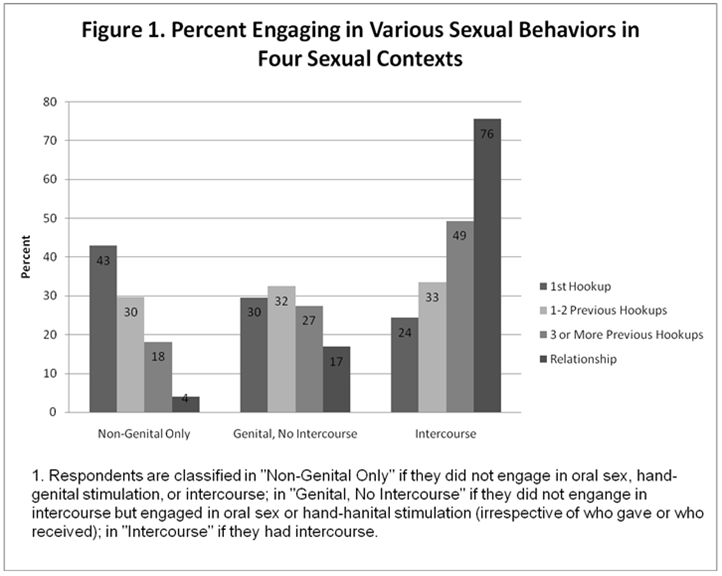

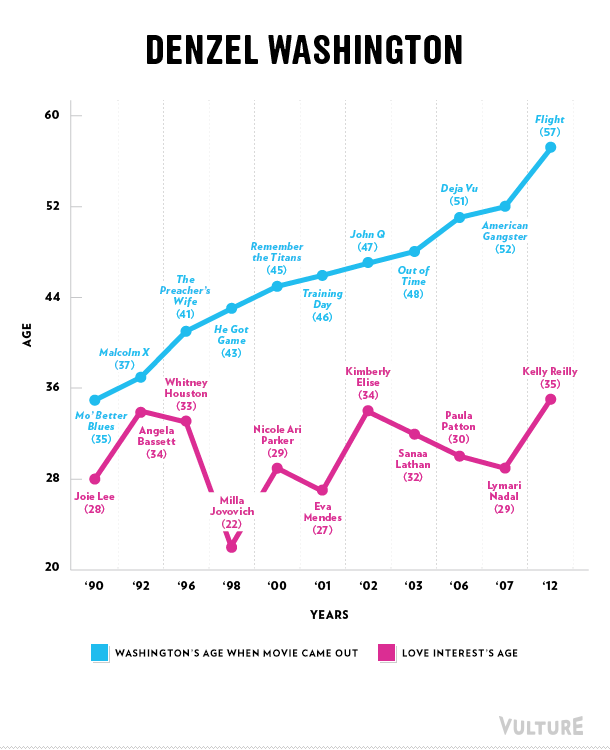

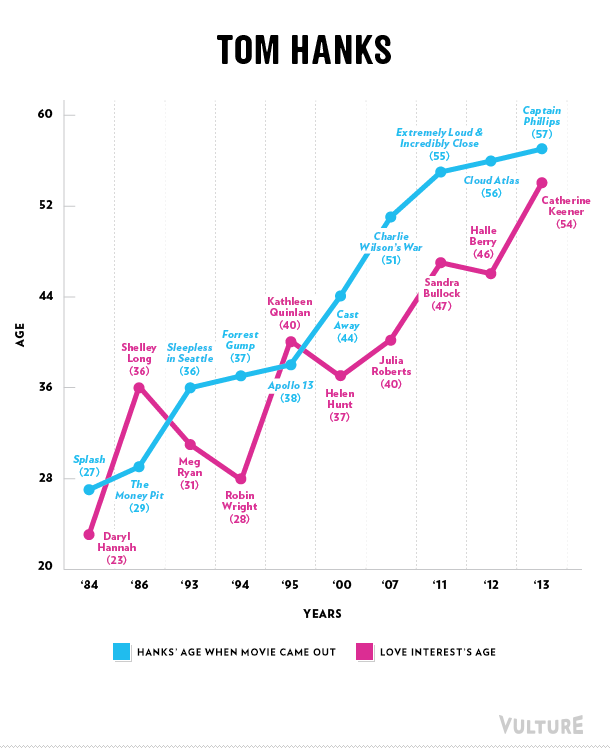

And it’s by hooking up that many students form these monogamous relationships. Roughly, they go from a first hookup, to a “regular hookup,” to perhaps something that my students call “exclusive” — which means monogamous but not in a relationship — and then, finally, they have “the talk” and form a relationship. As they get more serious, they become more sexually involved (source):

Come to think of it, this is how most relationships are formed — through a period of increasing intimacy that, at some point, ends in a conversation about commitment. Those crazy kids.

So, students are forming relationships in hookup culture; they’re just doing it in ways that Laird probably doesn’t like or recognize.

Finally, Laird assumes that relationships are emotionally safer than casual sex, especially for women. Not necessarily. Hookup culture certainly exposes women to high rates of emotional trauma and physical assault, but relationships do not protect women from these things. Recall that relationships are the context for domestic violence, rape and spousal murder.

It’s not hooking up that makes women vulnerable, it’s patriarchy. Accordingly, studies of college students have found that, in many ways, hookups are safer than relationships. A bad hookup can be acutely bad; a bad relationship can mean entering a cycle of abuse that takes months to end, bringing with it wrecked friendships, depression, restraining orders, stalking, controlling behavior, physical and emotional abuse, jealousy and exhausting efforts to end or save the relationship.

Laird’s views seem to be driven by a hookup culture bogeyman. It might scare him at night, but it’s not real. Actual research on hookup culture tells a very different story, one that makes college life look much more mundane.