It seems certain that the political economy textbooks of the future will include a chapter on the experience of Greece in 2015.

It seems certain that the political economy textbooks of the future will include a chapter on the experience of Greece in 2015.

On July 5, 2015, the people of Greece overwhelmingly voted “NO” to the austerity ultimatum demanded by what is colloquially being called the Troika, the three institutions that have the power to shape Greece’s future: the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank.

The people of Greece have stood up for the rights of working people everywhere.

Background

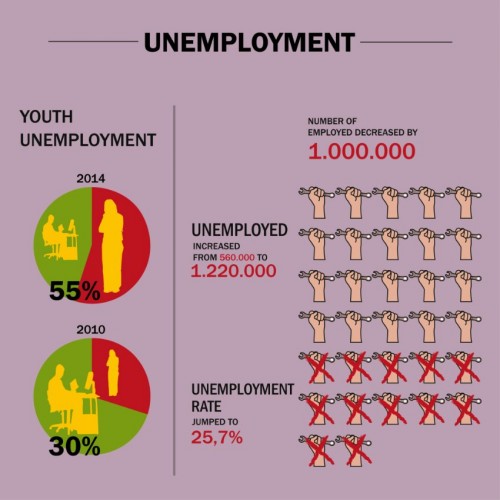

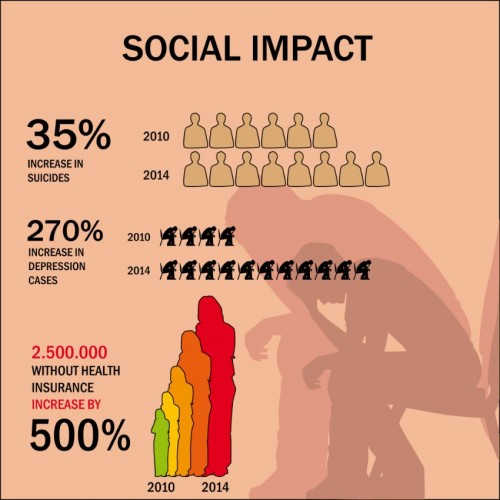

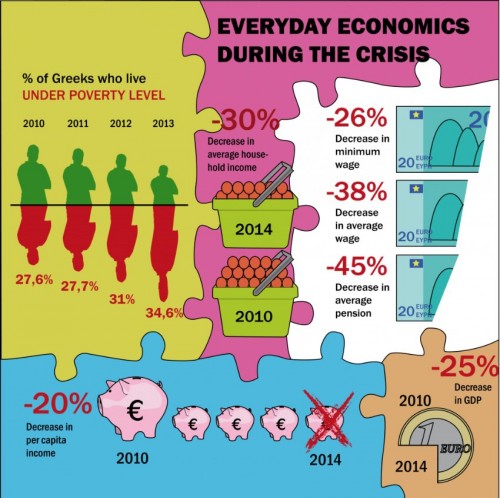

Greece has experienced six consecutive years of recession and the social costs have been enormous. The following charts provide only the barest glimpse into the human suffering:

While the Troika has been eager to blame this outcome on the bungling and dishonesty of successive Greek governments and even the Greek people, the fact is that it is Troika policies that are primarily responsible. In broad brush, Greece grew rapidly over the 2000s in large part thanks to government borrowing, especially from French and German banks. When the global financial crisis hit in late 2008, Greece was quickly thrown into recession and the Greek government found its revenue in steep decline and its ability to borrow sharply limited. By 2010, without its own national currency, it faced bankruptcy.

Enter the Troika. In 2010, they penned the first bailout agreement with the Greek government. The Greek government received new loans in exchange for its acceptance of austerity policies and monitoring by the IMF. Most of the new money went back out of the country, largely to its bank creditors. And the massive cuts in public spending deepened the country’s recession.

By 2011 it had become clear that the Troika’s policies were self-defeating. The deeper recession further reduced tax revenues, making it harder for the Greek government to pay its debts. Thus in 2012 the Troika again extended loans to the Greek government as part of a second bailout which included . . . wait for it . . . yet new austerity measures.

Not surprisingly, the outcome was more of the same. By then, French and German banks were off the hook. It was now the European governments and the International Monetary Fund that worried about repayment. And the Greek economy continued its downward ascent.

Significantly, in 2012, IMF staff acknowledged that the its support for austerity in 2010 was a mistake. Simply put, if you ask a government to cut spending during a period of recession you will only worsen the recession. And a country in recession will not be able to pay its debts. It was a pretty clear and obvious conclusion.

But, significantly, this acknowledgement did little to change Troika policies toward Greece.

By the end of 2014, the Greek people were fed up. Their government had done most of what was demanded of it and yet the economy continued to worsen and the country was deeper in debt than it had been at the start of the bailouts. And, once again, the Greek government was unable to make its debt payments without access to new loans. So, in January 2015 they elected a left wing, radical party known as Syriza because of the party’s commitment to negotiate a new understanding with the Troika, one that would enable the country to return to growth, which meant an end to austerity and debt relief.

Syriza entered the negotiations hopeful that the lessons of the past had been learned. But no, the Troika refused all additional financial support unless Greece agreed to implement yet another round of austerity. What started out as negotiations quickly turned into a one way scolding. The Troika continued to demand significant cuts in public spending to boost Greek government revenue for debt repayment. Greece eventually won a compromise that limited the size of the primary surplus required, but when they proposed achieving it by tax increases on corporations and the wealthy rather than spending cuts, they were rebuffed, principally by the IMF.

The Troika demanded cuts in pensions, again to reduce government spending. When Greece countered with an offer to boost contributions rather than slash the benefits going to those at the bottom of the income distribution, they were again rebuffed. On and on it went. Even the previous head of the IMF penned an intervention warning that the IMF was in danger of repeating its past mistakes, but to no avail.

Finally on June 25, the Troika made its final offer. It would provide additional funds to Greece, enough to enable it to make its debt payments over the next five months in exchange for more austerity. However, as the Greek government recognized, this would just be “kicking the can down the road.” In five months the country would again be forced to ask for more money and accept more austerity. No wonder the Greek Prime Minister announced he was done, that he would take this offer to the Greek people with a recommendation of a “NO” vote.

The Referendum

Almost immediately after the Greek government announced its plans for a referendum, the leaders of the Troika intervened in the Greek debate. For example, as the New York Times reported:

By long-established diplomatic tradition, leaders and international institutions do not meddle in the domestic politics of other countries. But under cover of a referendum in which the rest of Europe has a clear stake, European leaders who have found [Greece Prime Minister] Tsipras difficult to deal with have been clear about the outcome they prefer.

Many are openly opposing him on the referendum, which could very possibly make way for a new government and a new approach to finding a compromise. The situation in Greece, analysts said, is not the first time that European politics have crossed borders, but it is the most open instance and the one with the greatest potential effect so far on European unity…

Martin Schulz, a German who is president of the European Parliament, offered at one point to travel to Greece to campaign for the “yes” forces, those in favor of taking a deal along the lines offered by the

creditors.

On Thursday, Mr. Schulz was on television making clear that he had little regard for Mr. Tsipras and his government. “We will help the Greek people but most certainly not the government,” he said.

European leaders actively worked to distort the terms of the referendum. Greeks were voting on whether to accept or reject Troika austerity policies yet the Troika leaders falsely claimed the vote was on whether Greece should remain in the Eurozone. In fact, there is no mechanism for kicking a country out of the Eurozone and the Greek government was always clear that it was not seeking to leave the zone.

Having whipped up popular fears of an end to the euro, some Greeks began talking their money out of the banks. On June 28, the European Central Bank then took the aggressive step of limiting its support to the Greek financial system.

This was a very significant and highly political step. Eurozone governments do not print their own money or control their own monetary systems. The European Central Bank is in charge of regional monetary policy and is duty bound to support the stability of the region’s financial system. By limiting its support for Greek banks it forced the Greek government to limit withdrawals which only worsened economic conditions and heightened fears about an economic collapse. This was, as reported by the New York Times, a clear attempt to influence the vote, one might even say an act of economic terrorism:

Some experts say the timing of the European Central Bank action in capping emergency funding to Greek banks this week appeared to be part of a campaign to influence voters.

“I don’t see how anybody can believe that the timing of this was coincidence,” said Mark Weisbrot, an economist and a co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington. “When you restrict the flow of cash enough to close the banks during the week of a referendum, this is a very deliberate move to scare people.”

Then on July 2, three days before the referendum, an IMF staff report on Greece was made public. Echos of 2010, the report made clear that Troika austerity demands were counterproductive. Greece needed massive new loans and debt forgiveness. The Bruegel Institute, a European think tank, offered a summary and analysis of the report, concluding that “the creditors negotiated with Greece in bad faith” and used “indefensible economic logic.”

The leaders of the Troika were insisting on policies that the IMF’s own staff viewed as misguided. Moreover, as noted above, European leaders desperately but unsuccessfully tried to kill the report. Only one conclusion is possible: the negotiations were a sham.

The Troika’s goals were political: they wanted to destroy the leftist, radical Syriza because it represented a threat to a status quo in which working people suffer to generate profits for the region’s leading corporations. It apparently didn’t matter to them that what they were demanding was disastrous for the people of Greece. In fact, quite the opposite was likely true: punishing Greece was part of their plan to ensure that voters would reject insurgent movements in other countries, especially Spain.

The Vote

And despite, or perhaps because of all of the interventions and threats highlighted above, the Greek people stood firm. As the headlines of a Bloomberg news story proclaimed: “Varoufakis: Greeks Said ‘No’ to Five Years of Hypocrisy.”

The Greek vote was a huge victory for working people everywhere.

Now, we need to learn the lessons of this experience. Among the most important are: those who speak for dominant capitalist interests are not to be trusted. Our strength is in organization and collective action. Our efforts can shape alternatives.

Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.

Comments 19

peter campbell — July 7, 2015

People before profits is a worthwhile quest. It's pointless asking downtrodden victims to repay loans that they are ever likely to repay without tremendous self-wounding.

Bill R — July 8, 2015

The EU experiment needs to play out over time in respect to Greece with all fully engaged. The tired wing-nut, Soviet-era rhetoric in posts like this doesn't educate or help move the ball toward the goal.

John George — July 8, 2015

There is plenty of blame to go around. The timing of the austerity demands has wrong, but Greece's profligate spending was a root cause. Critically, so was the willingness of the northern banks to lend into such unsustainable spending. The 2010 plan did nothing but move the unsustainable Greek debt from the banks to the tax payers, mostly German tax payers. Now that the northern politicians who foisted this scam on the electorate are about the be exposed, they are panicking. A complete mess.

As the Euro was being introduced, most European economists understood it was probable that is was economically unsustainable and ill advised. Yet it proceeded anyway based on the belief that the just the act of attempting further economic integration would produce a more politically unified Europe. The grand experiment appears to be on verge of failing as both an economic and political devise. Most may be better off, starting with the Greeks, who have by most estimations the most self-contained economy in the EU.

fork — July 8, 2015

Thank you for this post. The ugly and mean narrative of lazy, entitled and corrupt Greeks sickens me.

The referendum in Greece and the reflexes of social scientists | Connectors Study — July 10, 2015

[…] Images blog, Martin Hart-Landsberg takes the opportunity of the referendum to discuss the corrupt economics behind Greece’s trouble, (and, to make the point that it seems certain that the political economy textbooks of the future […]

Christopher Powell — July 16, 2015

The data in these charts is helpful for visualizing the human costs of austerity.

At the same time, I feel that the heightened rhetoric used to frame these data distracts from the point being made. The Troika's policies are harmful to many people, but in what sense are they 'corrupt', precisely? Corruption involves the dereliction of one's institutional role to achieve a personal benefit. This article throws the word corruption around but doesn't show that any has taken place.

I also feel that as sociologists we should not be surprised when people and institutions act in their perceived self-interest. Of course the Troika would campaign vigorously against a "no" vote.

I'm very happy that Sociological Images takes a leftist position on social conflicts, but I'd rather see a clinical and intellectually rigorous left-wing analysis than yet another iteration of left-wing moralizing.

HarleyBray99 — December 1, 2020

Greece is a historical country in which many historical events took place. The Greek crisis is also a historical event that will also go down in history. But Greece had many moments long before that and the article https://passportsymphony.com/best-historical-sites-in-greece/ will cover each of these episodes in history. Learn and read about different countries and learn something new.

HarleyBray99 — December 1, 2020

Greece is a historical country in which many historical events took place. The Greek crisis is also a historical event that will also go down in history. But Greece had many moments long before that and the article https://passportsymphony.com/best-historical-sites-in-greece/ will cover each of these episodes in history. Learn and read about different countries and learn something new.

alarmingscab — March 12, 2024

Such stereotypes lead to the fact that women more and more often choose new trends in social behavior. Only those who are completely free can build their own destiny without restrictions. moto x3m

Lealia — May 29, 2024

Objective of crossy road is to cross a series of roads, rivers, and other obstacles without getting hit or falling off the screen.

Rosie Wilson — June 3, 2024

These kinds of prejudices are the root cause of the fact that women are increasingly opting to follow the latest trends in social connections game conduct.

Jonah — April 10, 2025

What were the implications of the IMF staff report on Greece released just before the referendum, and how did it reflect the conflicting interests between the Troika and the Greek government, particularly in relation to the political motivations behind the austerity measures io games?

Lisa Landis — April 11, 2025

The political economy textbooks of tomorrow will feature Greece’s 2015 crisis prominently. On July 5, 2015, Greeks decisively rejected austerity measures imposed by the Troika—the European Commission, IMF, and ECB—marking a bold stand for workers' rights. Amid six years of crushing recession, the social toll was immense. Like guessing wordle unlimited, analyzing Greece’s struggle unveils many hidden layers of resilience.