Saturday night, I went to the 7:30 showing of “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl.” The movie had just opened, so I went early. I didn’t want the local teens to grab the all the good seats – you know, that thing where maybe four people from the group are in the theater but they’ve put coats, backpacks, and other place markers over two dozen seats for their friends, who eventually come in five minutes after they feature has started.

That didn’t happen. The theater (the AMC on Broadway at 68th St.) was two-thirds empty (one-third full if you’re an optimist), and there were no teenagers. Fox Searchlight, I thought, is going to have to do a lot of searching to find a big enough audience to cover the $6 million they paid for the film at Sundance. The box office for the first weekend was $196,000 which put it behind 19 other movies.

But don’t write off “Me and Earl” as a bad investment. Not yet. According to a story in Variety, Searchlight is looking that “Me and Earl” will be to the summer of 2015 what “Napoleon Dynamite” was to the summer of 2004. Like “Napoleon Dynamite,” “Me and Earl” was a festival hit but with no established stars and debt director (though Gomez-Rejon has done television – several “Glees” and “American Horror Storys”). “Napoleon” grossed only $210,000 its first week, but its popularity kept growing – slowly at first, then more rapidly as word spread – eventually becoming cult classic. Searchlight is hoping that “Me and Earl” follows a similar path.

The other important similarity between “Napoleon” and “Earl” is that both were released in the same week as a Very Big Movie – “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” in 2004, “Jurassic World” last weekend. That too plays a part in how a film catches on (or doesn’t).

In an earlier post I graphed the growth in cumulative box office receipts for two movies – “My Big Fat Greek Wedding” and “Twilight.” The shapes of the curves illustrated two different models of the diffusion of ideas. In one (“Greek Wedding”), the influence came from within the audience of potential moviegoers, spreading by word of mouth. In the other (“Twilight”), impetus came from outside – highly publicized news of the film’s release hitting everyone at the same time. I was working from a description of these models in sociologist Gabriel Rossman’s Climbing the Charts.

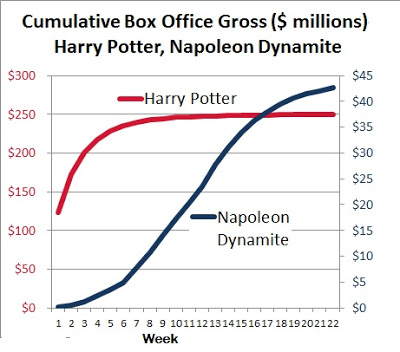

You can see these patterns again in the box office charts for the two movies from the summer of 2004 – “Harry Potter/Azkaban” and “Napoleon Dynamite.” (I had to use separate Y-axes in order to get David and Goliath on the same chart; data from BoxOfficeMojo.)

“Harry Potter” starts huge, but after the fifth week the increase in total box office tapers off quickly. “Napoleon Dynamite” starts slowly. But in its fifth or sixth week, its box office numbers are still growing, and they continue to increase for another two months before finally dissipating. The convex curve for “Harry Potter” is typical where the forces of influence are “exogenous.” The more S-shaped curve of “Napoleon Dynamite” usually indicates that an idea is spreading within the system.

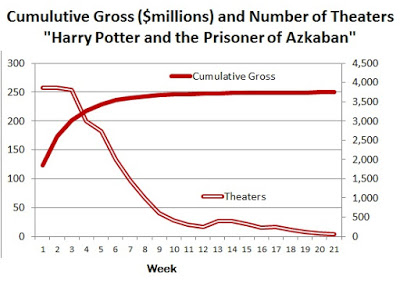

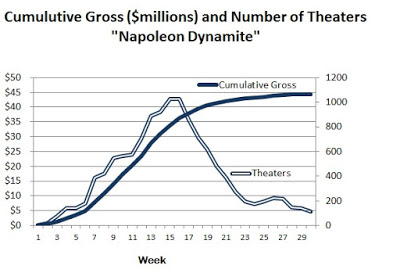

But the Napoleon curve is not purely the work of the internal dynamics of word-of-mouth diffusion. The movie distributor plays an important part in its decisions about how to market the film – especially when and where to release the film. The same is true of “Harry Potter.”

The Warner Bros. strategy for “Harry Potter” was to open big – in theaters all over the country. In some places, two or more of the screens at the multi-plex would be running the film. After three weeks, the movie began to disappear from theaters, going from 3,855 screens in week #3 to 605 screens in week #9.

“Napoleon Dynamite” opened in only a small number of theaters – six to be exact. But that number increased steadily until by week #17, it was showing in more than 1,000 theaters.

It’s hard to separate the exogenous forces of the movie business from the endogenous word-of-mouth – the biz from the buzz. Were the distributor and theater owners responding to an increased interest in the movie generated from person to person? Or were they, through their strategic timing of advertising and distribution, helping to create the film’s popularity? We can’t know for sure, but probably both kinds of influence were happening. It might be clearer when the economic desires of the business side and the preferences of the audience don’t match up, for example, when a distributor tries to nudge a small film along, getting it into more theaters and spending more money on advertising, but nobody’s going to see it. This discrepancy would clearly show the influence of word-of-mouth; it’s just that the word would be, “don’t bother.”

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Comments 18

Bill R — June 17, 2015

My hat is off to movie marketers, who I consider some of the best in the business and who appear to have been making a science of it for decades.

But quality rules in the end...

The highest grossing films of all time (adjusted for inflation)?

Gone With The Wind

Avatar

Star Wars

I try to go to the movies at least once a year and usually fail at the goal. But I do shoot for quality, like new James Bond and Star Trek flicks.

Charles Dummer — August 24, 2022

Looking for a way to watch your favorite movies without spending a fortune? Look no further than the Cinema HD app! This app offers users the ability to watch their favorite movies for free. Whether you're in the mood for a classic film or the latest blockbuster, Cinema HD has something for everyone. Download here: https://cinemahdv2.net/.

The app is easy to use and provides a high-quality viewing experience. You can search for your favorite movies and TV shows by title or genre, or browse through the featured selection. New titles are added regularly, so you'll always have something new to watch.

Cinema HD is the perfect solution for movie lovers on a budget. Why pay for expensive movie tickets when you can watch all the films you want for free? Download the app today and start watching your favorite movies!

Elis John — October 6, 2022

If you're looking for where to watch Hellraiser, then you can find it exclusively on Hulu. The series is currently in its first season, and new episodes are released every Friday. So far, the series has been well-received by fans and critics alike, and is definitely worth checking out if you're a fan of the horror genre.

https://www.streamingdigitally.com/watch-hellraiser-hulu-original/

Elis John — October 6, 2022

https://www.streamingdigitally.com/watch-hellraiser-hulu-original/

Doherty Nutrition — September 28, 2023

Because we all adore watching movies, I have something unique for you today. As an avid movie poster collector, I recently stumbled upon a collection of antique vintage movie posters that Www.cvtreasures.com piqued my interest. Because they so beautifully reflect the essence of cinematic history in a way that no modern reconstruction can ever match, these vintage works of art have given my basic movie room a new lease on life.

Markus — December 14, 2023

Many thanks for providing this information. I must inform you that while I agree with many of the things you raise, others may need more consideration.

idplayerdownload13 — March 5, 2024

LDPlayer stands out among Android emulators for its focus on gaming performance. It offers a smooth https://ldplayerdownload.com/ and lag-free experience for running even the most demanding mobile games on a PC. With LDPlayer, users can take advantage of features like keyboard mapping, multi-instance support, and customizable settings to optimize their gaming experience.

idplayerdownload13 — March 5, 2024

LDPlayer stands out among Android emulators for its focus on gaming performance. It offers a smooth and lag-free experience for running even the most demanding mobile games on a PC. With LDPlayer, users can take advantage of features like keyboard mapping, multi-instance support, and customizable settings to optimize their gaming experience.

idplayerdownload13 — March 5, 2024

LDPlayer stands out among Android emulators for its focus on gaming performance. It offers a smooth and https://ldplayerdownload.com/ lag-free experience for running even the most demanding mobile games on a PC. With LDPlayer, users can take advantage of features like keyboard mapping, multi-instance support, and customizable settings to optimize their gaming experience.

idplayerdownload13 — March 5, 2024

LDPlayer stands out among Android emulators for its focus on gaming performance. It offers a smooth and LDPlayer Download on lag-free experience for running even the most demanding mobile games on a PC. With LDPlayer, users can take advantage of features like keyboard mapping, multi-instance support, and customizable settings to optimize their gaming experience.

cartubeapp — March 12, 2024

The latest CarTube App for Apple CarPlay seamlessly integrates with your vehicle's infotainment system, providing instant access to a wealth of automotive content directly from your dashboard. With a simple connection between your iPhone and CarPlay-enabled head unit, you can effortlessly navigate through CarTube's extensive library of videos, reviews, and more without any distractions or interruptions.

cartubeapp — March 12, 2024

The latest CarTube App for Apple CarPlay seamlessly integrates with your vehicle's infotainment system, Latest CarTube App for CarPlay providing instant access to a wealth of automotive content directly from your dashboard. With a simple connection between your iPhone and CarPlay-enabled head unit, you can effortlessly navigate through CarTube's extensive library of videos, reviews, and more without any distractions or interruptions.

henryjak — March 25, 2024

It's always a strategic move to catch the early showing of a new release to avoid the seat-saving chaos that often occurs, especially with popular films like "Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. This phenomenon of claiming seats for friends is like trying to secure a spot in the exclusive Castle Premium Unlock, where everyone wants access but only a few can get in early enough.

aadan — June 6, 2024

Discover the tantalizing array of offerings on the kfc menu in South Africa, where every bite promises flavor-packed satisfaction. From the iconic Original Recipe chicken to the zesty Zinger Burgers and irresistible Wings, there's something to tantalize every taste bud. Don't forget to explore the sides, featuring golden fries, creamy coleslaw, and fluffy biscuits.

Lubanzi — June 8, 2024

Lunchtime is usually considered to be between 12 pm and 1 pm, but this can vary depending on cultural norms and work schedules. In South Africa, lunchtime is another name for the UK49s afternoon lottery draw and its Results History.

T. Calion — April 9, 2025

helo

Louvenia Feest — December 1, 2025

The way you explain the mix of word-of-mouth and strategic distribution really shows how unpredictable movie success can be. It’s similar to how some lesser-known films suddenly trend online when niche communities start sharing them. I see this happen on platforms people use for discovering new content too, like Kisskh APK Latest Version, where smaller titles often gain attention long after their release.

PPCine — December 6, 2025

Amazing how much word-of-mouth can shape a movie’s journey. Tools like PPCine make it even easier for people to discover hidden gems like this.