Dispatcher: Which entrance is that that he’s heading towards?

Zimmerman: The back entrance… fucking punks.

Dispatcher: Are you following him?

Zimmerman: Yeah.

Dispatcher: Okay, don’t do that.

Zimmerman: Okay.

If you followed the Zimmerman/Martin killing at all, you probably recognized that this is not what the dispatcher said. The correct transcript is:

Dispatcher: Okay, we don’t need you to do that.

Nowadays, we don’t tell people what to do and what not to do. We don’t tell them what they should or should not do or what they ought or ought not to do. Instead, we talk about needs – our needs and their needs. “Clean up your room” has become “I need you to clean up your room.”

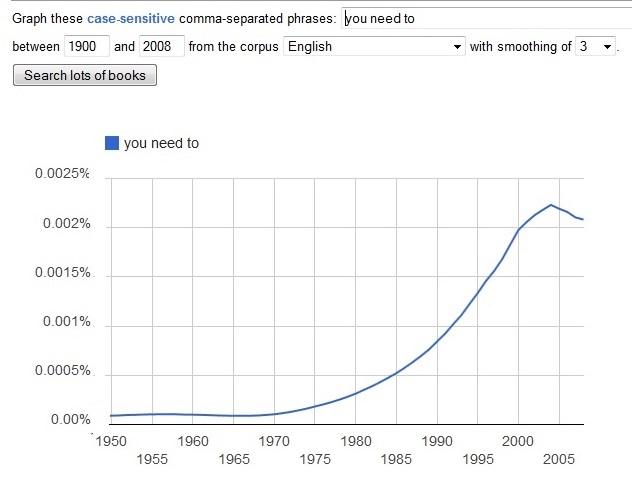

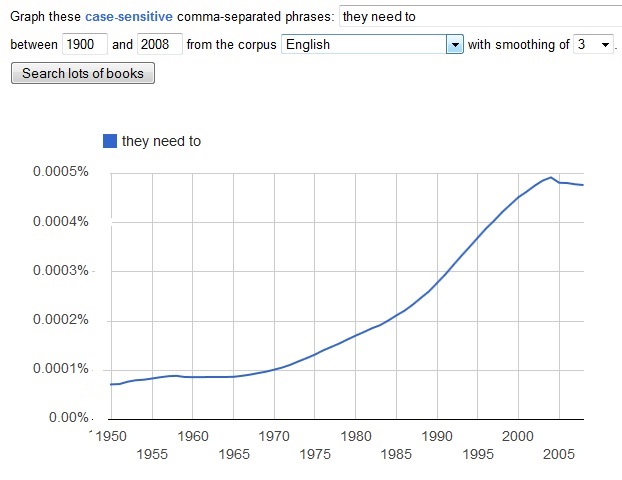

The age of “there are no shoulds,” the age of needs, began in the 1970s and accelerated until very recently. Here are Google n-grams for “you need to” and “they need to.”

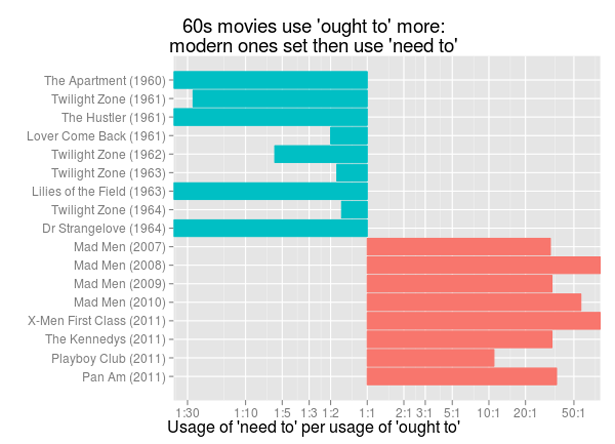

We don’t say, “The writers on ‘Mad Men’ ought to watch out for anachronistic language.” We say that they “need to” watch out for it. It was Benjamin Schmidt’s Atlantic post (here) about “Mad Men” that alerted me to this ought/need change. Schmidt created a chart showing the relative use of “ought to” and “need to.”

All the films and TV shows in the chart are set in the 1960s. But the scripts that were actually written in the 60s are more likely to use “ought”; the 60s scripts written in the 21st century use “need.”

Real imperatives (“Stop that right now”) claim moral authority. So do ought and should. But need is not about general principles of right and wrong. In the language of need, the speaker claims no moral authority over the person being spoken to. It’s up to the listener to weigh his own needs against those of the speaker and then make his own decision.

No wonder Zimmerman felt free to ignore the implications of the dispatcher’s statement. It was not a command (“Don’t do that”), it did not assert authority or the rightness of an action (“You should not do that”). It did not even state what the police department needed or wanted. It merely said that Zimmerman’s pursuit of Martin was not necessary. Not wrong, not ill-advised, just unnecessary.

If the dispatcher had spoken in the language of the 1960s and told Zimmerman that he should not pursue Martin, would Trayvon Martin be alive? We cannot possibly know. But it’s reasonable to think it would have increased that probability.

Philip Cohen, for what it’s worth, tells me that a TV commentator said that dispatchers have a protocol of not giving direct orders. If such an instruction led to a bad outcome, the department might be held accountable. So police departments’ efforts to avoid lawsuits may also have contributed to Martin’s death or, at least, the not-guilty verdict for Zimmerman.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Comments 15

Brutus — July 19, 2013

Are we really seeing a decline in 'ought to' in favor of 'should'?

A brief check shows an increase in both 'you need to' and 'you should' starting in the 1970's.

Try including "should" in addition to "ought to" when comparing movie scripts.

Another idiocy that killed Trayvon Martin | Homo Ludditus — July 19, 2013

[...] Language and Trayvon Martin’s Life: [...]

Julian — July 19, 2013

This seems relevant:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GjJCdCXFslY

How We Use Language and Trayvon Martin's Life — July 19, 2013

[...] post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner [...]

Elliott Hoey — July 19, 2013

This doesn't seem quite right to me, and in fact rather simplistic. It's a perfectly reasonable interpretation of these same n-gram data to say that 'need to' has come to replace 'ought to' as the preferred modal verb of obligation, which is to say, the illocutionary force is functionally identical. Under this view, there is no story here: 'need to' and 'ought to' accomplish the same work, and this analysis (and reporting) is rendered toothless.

Indeed, if the dispatcher had used 'ought to', this may have come off as too formal and reserved to GZ – a construction which could be disregarded as formulaic and non-binding. The words people use are usually the words they intend to use for the desired effect. They may choose to reformulate those words later on or correct a misunderstanding after the fact, but we can expect (and in practice _do_ expect) to produce the sufficient wording to accomplish what they intend to do.

Finally, imperatives and directives may be modulated according to moral authority, as the characterization in this article states, but I think the operative dimension is better stated as _epistemic_ authority, which is to say, the right/obligation to say/do something regarding some matter. In this view, the dispatcher did what was appropriate: they used the first person plural pronoun and spoke as the institutional authority "we", and made their agenda clear with "need" (as opposed to "ought", which implies a lesser obligation).

(also posted at Pacific Standard)

Ozy111 — July 20, 2013

Regardless of all that, this line doesn't read like an order at all. It isn't even imperative. If the dispatcher wanted to give an order, they should have given an order! "Maintain your position." "Do not pursue." Something like that.

That is how we operate in the Navy, at least. I would assume that police also have communication standards. I don't think dispatchers actually have command authority over anybody who calls them, so Zimmerman may not have been obligated to obey even if they did give an order. But this transcript shows no intention to command whatsoever. It's something you would say in a casual conversation, not in a combatant chain-of-command.

Of course, as pointed out by the last paragraph, this is probably deliberate. I can easily see it argued both ways if action were brought against the police department. If they fail to obey the "implied" command and meet a bad end, the police can say they advised appropriately but were ignored. If they obey it and meet a bad end that way, they can say that they didn't actually order them to do anything.

Village Idiot — July 20, 2013

A 911 dispatcher has no legal authority to order anyone to do anything so this discussion is irrelevant. Speculation about how the outcome may have been altered one way or the other if this or that had been done can go on forever (and in this case probably will). So while the Martin/Zimmerman case is topically relevant in some arcane sense, it's a very weak segue (at best) into a discussion of the use of imperative language in society in general.

It seems that anyone who can come up with a link between the Martin/Zimmerman case and their particular cause du jour (however tenuous) is not hesitating to do so, probably as an easy way to increase traffic. Maybe this tragedy wasn't about racism or profiling, it was about changes in the use of imperative language. No, it was about economics... No, it was the inevitably-tragic result of bad legislation... No, it was about [fill in the blank].

So far it looks like my original take on the case when it first broke was more or less correct: It's a Rorschach "culture-blot" that we're projecting our preconceived notions onto, whatever they may be. The "facts" of the case are just barely ambiguous enough to allow supporters of virtually any political agenda to point to them as proof they're right, and sure enough that seems to be what's happening and no one is budging on any "side" because the "facts" prove that each side is right and all the others are wrong simultaneously (it's a difficult rhetorical trick to pull off and doing it as successfully as it's being done in this case would make any Minister of Propaganda proud).

This case was a Perfect Storm of an ambiguous clusterfuck of facts and so was probably one of the worst examples for the media to focus on if they truly wanted to open up a constructive public dialogue about issues involving race, profiling, firearm laws, and all the other issues that are being tacked on to it to see if they'll stick. A "constructive" dialogue involves rational discussion and there's not much of that going on among the general public.

But it was the ideal example for the media to focus on (to the exclusion of most other incidents of a similar nature but less-ambiguous circumstances) if the goal was to set back race relations and inflame anger and resentment of a type that only serves to further divide people. An unconstructive "dialogue" would manifest as a series of preaching-to-the-choir monologues interspersed with a lot of yelling and fist-shaking, and sure enough I see more yelling and reactionary fist shaking than rational discussion going on and until that changes nothing else will.

Since "divide and conquer" is among the most reliably-effective and time-tested means of maintaining the status quo (which is always the ultimate goal of whoever happens to be benefitting the most from it at the time) then it could be that we're ALL being emotionally manipulated here by those who don't have society's overall best interests at heart (just their own).

black rabbit — July 20, 2013

Lots of good comments here covering flaws in this article. The only thing to add is that all the evidence, which was accepted by the jury in reaching their decision, shows that GZ did indeed follow the recommendation to stop following TM, and that it was TM who turned around and doubled back to confront and assault GZ instead of simply continuing to his destination.

Gül — July 21, 2013

As that dispatcher had no legal authority to order him to do something, this discussion is real "unnecessary". If you want your article to have some value, you should take away all this missinforming part.

fork — July 21, 2013

This discussion over the meaning of the dispatcher's words reminds me of this post about rape and saying no and how we communicate:

http://yesmeansyesblog.wordpress.com/2011/03/21/mythcommunication-its-not-that-they-dont-understand-they-just-dont-like-the-answer/

" People issue rejections in softened language, and people hear rejections in softened language, and the notion that anything but a clear “no” can’t be understood is just nonsense."

"Drawing on the conversation analytic literature, and on our own data, we claim that both men and women have a sophisticated ability to convey and to comprehend refusals, including refusals which do not include the word ‘no’, and we suggest that male claims not to have ‘understood’ refusals which conform to culturally normative patterns can only be heard as self-interested justifications for coercive behaviour."

I think that Zimmerman fully understood that the dispatcher was telling him not to pursue Martin, but, like a rapist, he didn't like what he heard and pretended not to hear.

chipgorman — July 22, 2013

Perhaps the dispatcher should have said "OK, we need you to remain in your vehicle until the police arrive." Not a direct order, unlikely to lead to a lawsuit-inducing "bad outcome"--a sad euphemism indeed in this case.

Smile! You’re on Candid Camera. | Sean McCarron — August 5, 2013

[...] I’m finally taking the plunge. I’ve been meaning to blog for quite a while. I’ve been told in no uncertain terms from people both personally and professionally, that I “really needed to start blogging” – an interesting choice of words considering this shift in diction. [...]

Links 1 – 10/8/13 | Alastair's Adversaria — August 9, 2013

[...] 26. Language and Trayvon Martin’s Life [...]