We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

A recent RadioLab podcast, titled The Bitter End, identified an interesting paradox. When you ask people how they’d like to die, most will say that they want to die quickly, painlessly, and peacefully… preferably in their sleep.

But, if you ask them whether they would want various types of interventions, were they on the cusp of death and already living a low-quality of life, they typically say “yes,” “yes,” and “can I have some more please.” Blood transfusions, feeding tubes, invasive testing, chemotherapy, dialysis, ventilation, and chest pumping CPR. Most people say “yes.”

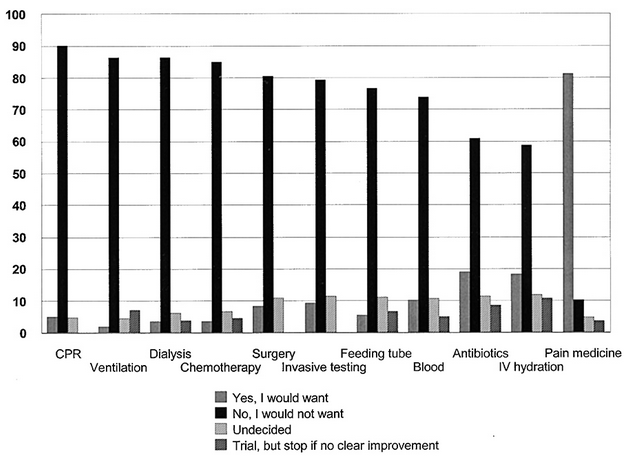

But not physicians. Doctors, it turns out, overwhelmingly say “no.” The graph below shows the answers that physicians give when asked if they would want various interventions at the bitter end. The only intervention that doctors overwhelmingly want is pain medication. In no other case do even 20% of the physicians say “yes.”

What explains the difference between physician and non-physician responses to these types of questions. USC professor and family medicine doctor Ken Murray gives us a couple clues.

First, few non-physicians actually understand how terrible undergoing these interventions can be. He discusses ventilation. When a patient is put on a breathing machine, he explains, their own breathing rhythm will clash with the forced rhythm of the machine, creating the feeling that they can’t breath. So they will uncontrollably fight the machine. The only way to keep someone on a ventilator is to paralyze them. Literally. They are fully conscious, but cannot move or communicate. This is the kind of torture, Murray suggests, that we wouldn’t impose on a terrorist. But that’s what it means to be put on a ventilator.

A second reason why physicians and non-physicians may offer such different answers has to do with the perceived effectiveness of these interventions. Murray cites a study of medical dramas from the 1990s (E.R., Chicago Hope, etc.) that showed that 75% of the time, when CPR was initiated, it worked. It’d be reasonable for the TV watching public to think that CPR brought people back from death to healthy lives a majority of the time.

In fact, CPR doesn’t work 75% of the time. It works 8% of the time. That’s the percentage of people who are subjected to CPR and are revived and live at least one month. And those 8% don’t necessarily go back to healthy lives: 3% have good outcomes, 3% return but are in a near-vegetative state, and the other 2% are somewhere in between. With those kinds of odds, you can see why physicians, who don’t have to rely on medical dramas for their information, might say “no.”

The paradox, then — the fact that people want to be actively saved if they are near or at the moment of death, but also want to die peacefully — seems to be rooted in a pretty profound medical illiteracy. Ignorance is bliss, it seems, at least until the moment of truth. Physicians, not at all ignorant to the fraught nature of intervention, know that a peaceful death is often a willing one.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard, The Huffington Post, and BlogHer.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 62

Nicole Dunham — June 24, 2013

This should probably come with a caveat that CPR, when administered RIGHT AWAY, still increases your odds more than just being like "aw well s/he'll probably be a goner anyway." I grew up watching my mom certify folks in CPR. She was an EMT for 20 years and, yeah, a lot of times she lost her patients after CPR. Most of the time, some of their ribs were broken in the process. But it seemed to be worth it to her for the people she was able to save... and it was also worth it for them, seeing as that they're alive and all.

Kylee Peterson — June 24, 2013

I think it's important to note that this is a particular kind of "bitter end" -- the graph is specifically "given a scenario of irreversible brain injury without terminal illness." It would be interesting to directly compare the results for doctors and laypeople for this exact question; I'm not so sure they'd be dramatically different.

Larry Charles Wilson — June 24, 2013

Having seen more than a few family and friends die, there is no doubt in my mind that I don't want any special efforts made to keep me alive. Give me the pain medication if needed and say "good-bye"

Unlike You, Most Physicians Don’t Want Emergency Treatment — June 24, 2013

[...] source quoted at The Society Pages suggests one reason for these trends has to do with the way physicians hold more realistic expectations of emergency treatments and [...]

Lisa — June 24, 2013

We've all said we want DNR tattood on our foreheads

Unlike You, Most Physicians Don’t Want Emergency Treatment | nWhy — June 24, 2013

[...] source quoted at The Society Pages suggests one reason for these trends has to do with the way physicians hold more realistic expectations of emergency treatments and [...]

Unlike You, Most Physicians Don’t Want Emergency Treatment - eNet VieweNet View — June 24, 2013

[...] source quoted at the Society Pages suggests one cause of these developments has to do with the way physicians hang extra life like expectations of emergency therapies and [...]

Doc Propofol — June 24, 2013

Being an anesthesiologist with a long experience in ICU, I can't help but react to this excerpt :

"First, few non-physicians actually understand how terrible

undergoing these interventions can be. He discusses ventilation. When a

patient is put on a breathing machine, he explains, their own breathing

rhythm will clash with the forced rhythm of the machine, creating the

feeling that they can’t breath. So they will uncontrollably fight the

machine. The only way to keep someone on a ventilator is to paralyze

them. Literally. They are fully conscious, but cannot move or

communicate. This is the kind of torture, Murray suggests, that we

wouldn’t impose on a terrorist. But that’s what it means to be put on a

ventilator."

People in this setting, when they require neuromuscular blockade (NMB) (ie muscular paralysis) in order to adapt to ventilator settings also receive sedation (ie general anesthesia) so that THEY ARE NOT CONSCIOUS.

This is basic ethics in ICU, so that patients don't fell trapped inside their own bodies.

Should the condition improve, then NMB is discontinued, later when it has worn off, sedation is also stopped and weaning from mechanical ventilation is considered, with patient no longer paralysed and partially able to communicate.

BC78 — June 24, 2013

The paradox, then — the fact that people want to be actively saved if they are near or at the moment of death, but also want to die peacefully — seems to be rooted in a pretty profound medical illiteracy. Ignorance is bliss, it seems, at least until the moment of truth. Physicians, not at all ignorant to the fraught nature of intervention, know that a peaceful death is often a willing one.

"Medical illiteracy" seems like a loaded term; it's not like actual illiteracy, or innumeracy, where someone lacks a basic skill that helps them get along in day-to-day life (reading street signs, avoiding crushing debt, etc.). "Medical illiteracy" seems more like, say, "automobile illiteracy"--not having expertise in a particular area where laymen usually defer to specialists. Of course non-doctors who have neither medical training nor experience with end-of-life care are going to make assumptions and hold opinions that trained physicians wouldn't.

This raises the question of whether "ignorance is bliss" better describes the attitudes of patients and families who ignore medical realities, or the attitudes of doctors who fail to fully inform patients and families for whatever reason.

Should we be focusing on the general public's "medical illiteracy," or on the apparent failure of the medical community to convey information that's common knowledge among doctors? If a poll of mechanics found that they'd junk a car in 90 percent of cases where the average customer would spend thousands on repairs, I think we'd be talking less about the "illiteracy" of the customers and more about the sinister motives or incompetence of the experts.

It's hard to get a feel for what's really going on here without more information. For example:

1. What exactly are doctors telling patients and their families? Are they telling them everything the doctors know, and allowing them to make their own decisions? Or are they soft-pedaling realities that they themselves find so horrifying that they'd choose to limit end-of-life care?

2. When it gets down to it, do doctors and their families forego end-of-life care at much greater rates than the general population? If not, it may be less a question of "illiteracy" and more an issue of human nature--we can say, rationally, that we'd rather die peacefully than struggle on in pain, but in the end it's just in our nature to resist death at almost any cost.

Bobby Kenis — June 24, 2013

I still have a hard time understanding the strong disapproval of "blood."

It must be because I just don't know the whole process. I just think about donating plasma (with a large gauge needle) which is completely painless to me and I imagine receiving blood uses a similar needle (?) So I just have difficulty comprehending why one wouldn't want the singular remedy "blood" if that is what was needed for life saving.

Dr. Everyman — June 24, 2013

I am a physician board certified in anesthesiology and I find these statistics ludicrous. I see no references given in the article. Where do these data come from?

I know thousands of physicians, and while they may not wish to have rescussitation efforts continued in "hopeless" situations, MOST situations in which the above interventions are started are not "hopeless."

Example: The graph says 80% of physicians would not undergo "Surgery" to save their lives. REALLY? Appendicitis is a surgical emerergency. Without it an overwhelming majority of patients will die. With an appendectomy almost no patients will die. Less than 3 per 1000 patients will die with surgery. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1421275/)

All physicians know this. Do they hate life so much that they would say "Oh well, don't do surgery. I'm most certainly going to die without it, and I would most likely live with it, but let me die anyway. No surgery for me."

That's just stupid.

Looking at the other interventions in the list is equally disturbing to me: They are all meant to be short term interventions intended on preserving the patient's life in a crisis. Short term pain. Long term gain. Really? These people who have undergone the pain and trials of difficult colleges, medical school, grueling residency and difficult practice will now just say, "Oh, I give up, don't give me IV fluids"? This article is ridiculous, and that is underscored by the lack of any reference to the statistics they quote.

People, ALWAYS ask "On what evidence do you base that conclusion."

Those words will protect you against charlatans, politicians, and various other deceivers you will encounter on an ever increasing basis in our world.

Cum vă moară medicii și non-medicii | TOTB.ro - Think Outside the Box — June 25, 2013

[...] Sursa: Sociological Images [...]

Cum vor să moară medicii și non-medicii | TOTB.ro - Think Outside the Box — June 25, 2013

[...] Sursa: Sociological Images [...]

[links] Link salad suddenly explodes | jlake.com — June 25, 2013

[...] How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? — This has been a serious topic of discussion hereabouts lately. [...]

Dianne Porter — June 25, 2013

I used to work as a registered nurse. I believe a humane death where death is accepted as the end of life is a human right. I am strongly for every effort to be made to manage pain at that stage of life.

psittacid — June 25, 2013

Fighting for health is very worthwhile. Fighting against death is futile. The two are easily mistaken. The trick is not to resist death when that's all that is left.

June 25: O The Humanities! Edition | New Religion and Culture Daily — June 25, 2013

[...] How to die like a doctor (and could this simple idea reform health care, I [...]

Doug Arenberg — June 25, 2013

Dr. Ken Murray is obviously not an intensivist. We rarely, if ever, "paralyze" patients for ventilaition. We do use sedation, which we regularly stop in order to assess someones synchrony with the ventilator as well as their comfort level. when we do (on rare occasion) paralyze patients, it is absolutely standard to use deep sedation.

That said, I completely agree with the gist of this article which is that American's don't "die well", not because we force unnecessary death prolonging treatment upon them, but because they choosse not to "die well".

Enturian — June 25, 2013

Dr. Everyman:

You must have missed this caveat: "But, if you ask them whether they would want various types of interventions, were they on the cusp of death and already living a low-quality of life, they typically say “yes,” “yes,” and “can I have some more please.” Blood transfusions, feeding tubes, invasive testing, chemotherapy, dialysis, ventilation, and chest pumping CPR. Most people say “yes.”

But not physicians."

Many of the healthcare professionals and scientifically trained people that I know can look at the situation, read the research and draw a line. Most other patients are ill prepared to do so and lack a knowledgeable patient advocate that can navigate the science and the system. They get drawn in by incrementalism, lack of understanding of the clinical options and a misunderstanding of statistics.

Were I to have a tumor, I'd want to know if it were operable and whether or not surgery would significantly improve my quality and quantity of life. If it seemed likely, I'd do it. However, if radical surgery were only likely to "double" my long term survival from 0.5% to 1%, or if if it were to "triple" my survival from 1 month to three months, I'd spend what time I had left getting my affairs in order and connecting with friends and family while I still could. Same for chemo, transfusions, vents, dialysis, feeding tubes, and even antibiotics. Why spend a hundred grand to be more miserable for another month or two?

Most patients do not understand the difference between relative and absolute risks. Many physicians with whom I interact, don't have a mastery of the concepts either. Physicians are trained to extend life, but it is the patient that has to decide if it is worth it.

One friend of mine finally overcame breast cancer in her third bout with it. After the disfiguring surgery, horrible chemo, the radiologists finally cured it. Unfortunately they also "cooked" her and caused her to die of the deep painful burns resulting from the treatment. On the whole, she would have (and expressed that she would have) preferred to go more gently into that good night 6-12 months earlier without all of the open wounds, internal burns, pain and suffering for her and her family.

Another friend, during his second bout with melanoma, was entered into an interfereon trial. He lost 50 pounds and and his mind to the side effects of that particular treatment regimen. With no progress on the melanoma, he asked to quit the program.

All the docs encouraged him to stay in it, despite having destroyed any semblance of quality of life, so that they could get the data from his remaining time as a lab rat in the study. He complied for a while and died with great suffering for him and his friends and family. Too bad for the docs, that they killed him before the trial period was over. So, they didn't even get some of the data results for which they were willing to kill him.

If I had an SCA, I'd want CPR and defibrillation, pull out the stops! If, however, it becomes hopeless that I will be able to return to a relatively functional and useful life...well, then pull out the tubes.

Don't Mind Me — June 25, 2013

See even doctors like to be high! Its human nature. If I had a choice to be "high" or normal when I die... I'd pick HIGH!!!

AlanThinks — June 26, 2013

30% of Medicare expenditures are made on people in the last year of the life, primarily for hospital services. Only around 1% of Medicare is spent on hospice with admissions on average less than a week before death. The problem with the long term financing of Medicare, which is at the center of the federal deficit political deadlock in Washington, is a problem of how we die in this country.

How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? | pootimes — June 26, 2013

[...] How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? [...]

Unlike You, Most Physicians Don’t Want Emergency Treatment | HNO — June 28, 2013

[...] source quoted at The Society Pages suggests one reason for these trends has to do with the way physicians hold more realistic expectations of emergency treatments and [...]

Why Is the Way Physicians Want to Die So Different From the Rest of Us? - — July 1, 2013

[...] post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner [...]

ER doc in San Francisco — July 3, 2013

Some of my medical colleagues very legitimately point out the vagueness of some of these questions (e.g. would you want surgery) as well as the author's clear unfamiliarity with the use of paralytics in ventilated patients (for non-medical readers, please rest assured, we always sedate-- heavily).

Nevertheless, I commend the researcher's analysis of the public's perception of the effectiveness of CPR. As the guy that usually has to have "the talk" with patient's families, I can't agree more with the suggestion that we docs just aren't very good at communicating futility. The average person who watched "ER" regularly when it was on TV probably thinks that grandpa will be smiling at home in a few days if someone just yells "Clear!" and put those zappy things on his chest. The reality of CPR is a lot more brutal, and a lot less successful.

Stayin Alive « Snippets of random — July 5, 2013

[...] In fact, CPR doesn’t work 75% of the time. It works 8% of the time. That’s the percentage of people who are subjected to CPR and are revived and live at least one month. And those 8% don’t necessarily go back to healthy lives: 3% have good outcomes, 3% return but are in a near-vegetative state, and the other 2% are somewhere in between. With those kinds of odds, you can see why physicians, who don’t have to rely on medical dramas for their information, might say “no.” [link] [...]

Linkspam mit Geek-Girls*, Wettbewerben, Disney und Quantenphysik — July 5, 2013

[...] Wie möchten Mediziner und Nicht-Mediziner sterben? Lisa Whade berichtet von erstaunlichen Erkenntnissen (Englisch). [...]

How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? | Conscious Life News — July 5, 2013

[...] Wade | TheSocietyPages | Jun 24 [...]

Doctors and Dying — July 6, 2013

[...] Source: [...]

Fanon — July 6, 2013

"This is the kind of torture, Murray suggests, that we wouldn’t impose on a terrorist."

Hımm. So there are some other kinds of tortures that you would impose on a terrorist, but not this one, eh? For me, this clearly shows the extent to which torture was normalised and graded in the minds of some people.

The 'we' has the authority to impose some tortures as the master of the globe, but, thanks god, 'we' also has some mercy left in his heart so that they will save the terrorists from the worst of tortures. Ah democrats, I always fear them.

Shame on Murray.

Becky — July 9, 2013

I was on a ventilator for a week and it saved my life. It was certainly not pleasant, but I was not conscious for 5 of the days. I don't remember fighting the rhythm of the machine the 2 days I was conscious before they pulled the tube out. I will have lung problems for the rest of my life, but they are manageable and don't affect the quality of my life. The doctors gave me a 30% chance of making it, so I wouldn't make a decision for a loved one based on that kind of estimate either. I guess I am in the "Trial, but stop if no clear improvement" camp.

For class July 15th | monkeypuzzletree22 — July 11, 2013

[...] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2013/06/24/how-do-physicians-and-non-physicians-want-to-die/ [...]

mograph — December 31, 2013

My 82-year-old father died of what was suspected as ALS (we eschewed the confirming autopsy) after about two days in hospital. I find it difficult to forget the image of him, weakly pulling at the ventilation tube, trying to pull it and the feeding tubes out. He was not paralyzed.

He was all there, still sharp, but couldn't talk because of the tube, and could barely muster the strength to gesture by opening and closing his eyes.

It was clear he wanted to go.

If I had the legal power, I would have let him go.

That was not life.

How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? | Ethics, Politics & Culture in Medical History — December 31, 2013

[…] How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die?. […]

Jason Surratt — January 1, 2014

Interesting but how do they actually behave.

Sunday Morning Medicine | Nursing Clio — January 5, 2014

[…] A comparison of how physicians and non-physicians want to die. […]

GVB — February 22, 2014

I hate my life. I married a woman who is totally incompetent and

unwilling to undergo fertility treatment even though she knew how

important kids were to me. She can't do anything because she gets panic

attacks. The irony is that she gets panic attacks because she is so

stupid that she can't do anything. Not drive, take public

transportation, stand in line at a grocery store, cook, even cross the

damn street sometimes, she breaks down trying to figure out a washing

machine. I feel so stupid for marrying her. I wouldn't now dare bring

children into this world with her. If I am late coming home from work

one day, I have no doubt the child would be dead one day from being left

out in the cold, being fed something spoiled or completely dehydrated.

I can't bring myself to leave her because she is so pathetic, and I am

admired so much by her family and mine. I am a professional making over $240k and do nothing but work. And no,

taking vacations with her is not an option because she is too afraid to

fly, of course. So all I have to do for the rest of my life is work like a slave

and come home to stupidity. I get that I am really the stupid one who put

myself in this situation. No disagreement there. I admit it's all my fault. I just realized this too late. Her whole

family even implicitly understands how pathetic she is and I can tell they

feel sorry for me yet hope that I can continue so she is no longer a burden to them. And so, I am thinking

very seriously about ending my life. I'm just doing some research on how

to best accomplish that. I would preferably do it where no one would find my body (at sea, deep in the woods, etc.) so I don't burden anyone with that pain and memory, yet I realize that having a dead body is important for estate planning purposes (yes, I will leave the wife plenty of money, but also to my beloved niece and nephew) So, is there a way I can medically induce death without making it obvious that it is suicide? I heard overdosing on insulin can accomplish this, and coroners very rarely test for insulin overdose. Thank you reading this. No lectures, please.

Medical interventions: physicians don’t want them. | Tom's News and Views — February 26, 2014

[…] an article you may want to read. It’s titled, How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die?. The article reports the results of a survey in which physicians gave very different answers than […]

How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? | ΡΟ Π ΤΡ Ο Ν — March 17, 2014

[…] How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die?. […]

How Do Physicians and Non-Physicians Want to Die? – Nadia McLaren | — April 21, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2013/12/31/how-do-physicians-and-non-physicians-want-to-die/ [Extract] What explains the difference between physician and non-physician responses to these types of questions. USC professor and family medicine doctor Ken Murray gives us a couple clues. First, few non-physicians actually understand how terrible undergoing these interventions can be. He discusses ventilation. When a patient is put on a breathing machine, he explains, their own breathing rhythm will clash with the forced rhythm of the machine, creating the feeling that they can’t breath. So they will uncontrollably fight the machine. The only way to keep someone on a ventilator is to paralyze them. Literally. They are fully conscious, but cannot move or communicate. This is the kind of torture, Murray suggests, that we wouldn’t impose on a terrorist. But that’s what it means to be put on a ventilator. A second reason why physicians and non-physicians may offer such different answers has to do with the perceived effectiveness of these interventions. […]

Would You Rather Be Born Disabled or Become Disabled? (Part Two) | Painting On Scars — September 28, 2014

[…] most dear. And his other arguments about the drawbacks to longevity are as thought-provoking as physicians’ personal opinions on life-saving interventions. But his decision to openly denounce dependence and weakness as […]