Cross-posted at BlogHer and The Huffington Post.

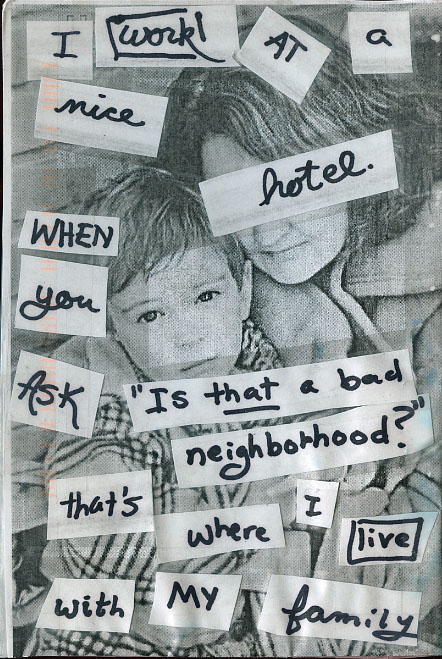

This PostSecret confession breaks my heart:

Most hospitality workers — especially those at high end hotels — routinely interact with people with significantly more economic resources than they. This is an interesting point of contact analyzed exquisitely by Rachel Sherman in her book, Class Acts: Service and Inequality in Luxury Hotels (review here).

Sherman observes that workers and guests often minimized the class differences between them, even as enacting relationships strongly structured by their relative privilege. Instead of obsessing about the wealth and privilege of the guests or ranting about the injustice of class inequality, though, they “normalized” it such that it was mostly invisible:

Unequal entitlements and responsibilities were not obscured, because they were perfectly obvious and well-known to interactive workers. Nor were they explicitly legitimated, since workers rarely talked about them as such. Rather, they simply became a feature of the everyday landscape of the hotel. Conflicts over unequal entitlement were couched in individual rather than collective terms and in the language of complaint rather than critique (p. 17).

Interestingly, this confession bucks the trend, which makes me wonder: if normalizing becomes habitual, what upsets it? What knocks class consciousness back into full view? In this case, it might have been the personal nature of the question. When the guest expresses worry about the safety of the worker’s own neighborhood, questioning whether “someone like her” should go “somewhere like that,” perhaps it is to direct of a contrast to ignore.

Also inspired by Class Acts, see Employee “Empowerment” and Corporate Culture.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 34

Rachel Melendes — April 16, 2013

I only have one thing, www.hyatthurts.org

Tusconian — April 16, 2013

I have to wonder, having heard similar comments working in the service industry (though much less often, as it wasn't a terribly high-end place, but it did attract a lot of quite wealthy people looking for an "authentic experience") do these people think that those in the service industry are paid so much that they must be on the same socioeconomic plane as them? Do they not even see members of the service industry as human beings with paychecks and families and houses to go to that may not be in lavish neighborhood? Or do they dehumanize "those people" in "those neighborhoods" so thoroughly that they can't even wrap their minds around the idea that they might interact with them in any sense, even as the person who serves them coffee or cleans their room for minimum wage or less? Like "the person at the desk seems so civilized and clean, and I know THAT neighborhood is only populated with dirty layabouts who spend all of their time mugging decent people."

Andrew — April 17, 2013

Of all of the examples of class-related insensitivity and ignorance that service workers encounter on an hourly basis (and not just in high-end places), this example seems about as benign as it gets.

First off, how on earth is a customer supposed to know what neighborhood you live in? It's not as though I've ever been given a nametag that says "Andrew de la Ghetto."

And even at that, I have lived in some neighborhoods that I would certainly describe as "bad," especially to an outsider who doesn't know the way around. Part of being working-class is that you often have to live where you can afford, and where you can get to work from easily, not necessarily where you think is a nice place to raise your family. Hearing a wealthier person deriding your hood is a bit like hearing someone outside your family insulting your least favorite relative; you're like, "sure, technically you're right, but f*** you!"

But if it breaks your heart, then I'm afraid you're not cut out for the hospitality business.

Ted_Howard — April 17, 2013

I understand why someone would ask that question. What guests are really asking is whether that neighborhood is a high-crime area. If I'm at an unfamiliar location I usually just look up the crime statistics of a neighborhood. In foreign countries where the data often isn't easily searchable (or if I don't speak the native language), I will kindly ask a hotel worker. I usually phrase the question a bit more delicately though. I usually say something to the effect that I'm unfamiliar with the neighborhoods around here and, like everywhere, criminals try to take advantage of tourists - what areas of this city should I avoid?

But I want to touch on something else. You wonder why workers don't rant about the "injustice of class inequality." It's because the overwhelming majority of Americans do not want a classless, egalitarian society. The only classless societies that have ever existed are where everyone is equally poor. The incentive for high-ability people to innovate is largely, but not exclusively, about those individuals receiving high-payoffs and most people understand this. The public debate is how we balance that incentive provision, which will inevitably lead to a class society, with alternative goals of providing public goods, defense, aid for less well-off etc.

Most people only get angry when they perceive wealth inequities as a result of unfair privilege. This includes, broadly speaking: crony capitalists, wealthy heirs, patent trolls, industries with large, uncompensated externalities etc. This is why protests happened in front of Wall Street firms rather than something like Apple. People perceive Steve Jobs and his fellow investors as hard-workers who contributed to the well-being of others and hence their wealth is deserved. Whereas Wall Street bankers largely high-jacked the system to get implicit bailout guarantees and no subsequent risk regulation (bailout guarantees + no risk regulation is a recipe for disaster) and hence their wealth is viewed as undeserved.

cinnamon50 — May 26, 2013

as it is told, when Alexander Berkman assasinated Frick, Berkmann was astonished that the workers were not approving of his act

in other words, isn't this like stuff known since like the dawn of time ?

Underground Demography: Race, Class, and the Subway Systems of Large U.S. Cities - — June 10, 2013

[...] Despite the social class segregation in housing, in cities like New York and Chicago, people of vastly different economic circumstances are likely to share the same subway car, at least for a few stops. Yet I don’t get a sense of strong resentment or even envy among the have-nots (though I wish I had systematic data on this). This is similar to the findings of Rachel Sherman, who studied how workers at high-end hotels thought of their guests. [...]

Janelle — September 1, 2019

I have to disagree with Ted Howard about why us workers don't rant about the injustice of class inequality. It's not that we like it or agree with it, it's more like class discrimination is so common in everyday life that we get used to it. Sometimes we don't even consciously realize it. I suppose it still causes stress even if you don't notice it. Sad but true.

We're pretty much expected to put up with it, especially in customer service. Also, what would be the point of freaking out over every little thing. It wouldn't change anything you'd just be angry all the time.

Janelle — September 1, 2019

Another point I disagree with Ted Howard on is just because we have to deal with class discrimination in order to keep our jobs or get by in life doesn't mean that's it not hurtful or should be allowed to continue.

I disagree that people don't want a more equal society. There will probably always be some kind of social classes. But I think many people are getting fed up with the huge gap. The interest in politicians like AOC, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren proves that.

HaroldTd — July 12, 2023

In hotels you often come across different classes of foreigners, and this is wonderful. Especially interesting are the meetings with the Arabs and the British. Their differences in culture and language create a bridge for mutual exchange of experience. But thanks to the translator, we find a common language and learn from each other. This experience expands my global perspective and shows how the interaction of different cultures can lead to mutual understanding and friendship.

Ravi kapoor — February 16, 2025

Goa is a traveler’s paradise, offering stunning beaches, vibrant culture, and a perfect blend of adventure and relaxation. Among its many beautiful destinations, Colva Beach in South Goa stands out for its pristine white sands, swaying palm trees, and peaceful ambiance. If you're planning a trip and searching for Resorts Near Colva Beach Goa look no further than Soul Vacation—a boutique wellness resort that promises tranquility, comfort, and rejuvenation.

Mattis Guzel — August 16, 2025

Guests seeking a luxurious getaway often investigate Mirbeau Inn and Spa Rhinebeck customer service before booking their stay. Visitors comment on the spa experience, room quality, and staff attentiveness. While many highlight relaxing treatments and beautiful surroundings, some reviews mention challenges with reservation scheduling or billing issues. Overall, it helps travelers gauge whether the inn matches their expectations for a high-end retreat.