Cross-posted at Asian-Nation and Racialicious.

As an undergraduate majoring in linguistics, I was fascinated with the concept of endangered languages. Colonization, genocide, globalization, and nation-building projects have killed off untold numbers of languages. As linguist K. David Harrison (my undergrad advisor) tells NPR, speakers of stigmatized or otherwise less-favored languages are pressured to abandon their native tongue for the dominant language of the nation and the market (emphasis mine):

The decision to give up one language or to abandon a language is not usually a free decision. It’s often coerced by politics, by market forces, by the educational system in a country, by a larger, more dominant group telling them that their language is backwards and obsolete and worthless.

These same pressures are at work in immigrant-receiving countries like the United States, where young immigrants and children of immigrants are quickly abandoning their parents’ language in favor of English.

Immigrant languages in the United States generally do not survive beyond the second generation. In his study of European immigrants, Fishman (1965) found that the first generation uses the heritage language fluently and in all domains, while the second generation only speaks it with the first generation at home and in limited outside contexts. As English is now the language with which they are most comfortable, members of the second generation tend to speak English to their children, and their children have extremely limited abilities in their heritage language, if any. Later studies (López 1996 and Portes and Schauffler 1996 among them) have shown this three-generation trend in children of Latin American and Asian immigrants, as well.

The languages that most immigrants to the U.S. speak are hardly endangered. A second-generation Korean American might not speak Korean well, and will not be speaking that language to her children, but Korean is not going to disappear anytime soon — there are 66.3 million speakers (Ethnologue)! Compare that with the Chulym language of Siberia, which has less than 25.

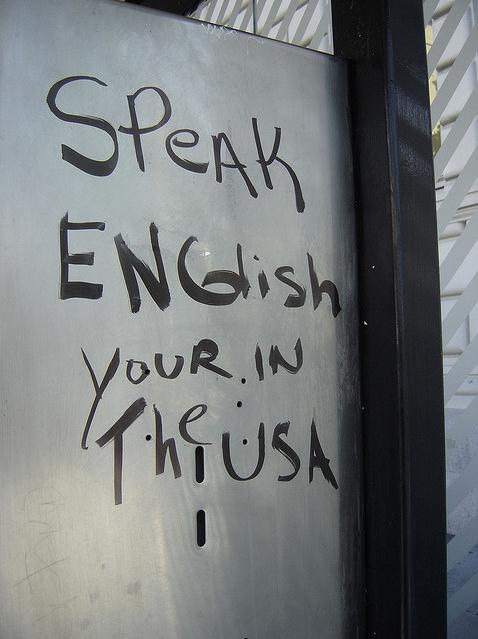

Even if they’re not endangered per se, I would argue that they are in danger. While attitudes towards non-English languages in the U.S. seem to be improving, at least among wealthier and better educated people in some more diverse cities and suburbs, the stigma of speaking a non-English language still exists.

How many of you have:

- been embarrassed to speak your heritage language in front of English speakers?

- been reprimanded for speaking your heritage language in school?

- been told to “go back to [country X]” when someone overhears you speak your heritage language?

I’ve heard innumerable stories about parents refusing to speak their native language to their children. Usually, the purported rationale is that they do not want the child to have language or learning difficulties, a claim that has been debunked over and over again by psychologists, linguists, and education scholars.

I’m sure that these parents truly believe that speaking only English to their children will give them an edge, though the reverse is true. What I wonder is how much this decision had to do with an unfounded belief about cognition and child development, and how much it had to do with avoiding the stigma of speaking a language that marks you as foreign, and as “backwards and obsolete and worthless”?

Calvin N. Ho is a graduate student in sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles studying immigration, race/ethnicity/nationalism, and Asian diasporas. You can follow him at The Plaid Bag Connection and on Twitter.

Comments 22

Anna — April 3, 2013

In general, here you view the reluctance of parents to pass on their language to their children as stemming from (false) worries about cognitive development and also from experiencing prejudice when speaking one's native language. While these are certainly a part of it - and are likely highly significant factors for many people - there are many more intricate issues involved, which really complicate the matter of how easy and beneficial it is for individuals and society to both encourage and support bi/multi-lingualism of immigrant groups.

Not saying I don't personally support retaining one's native language as an immigrant - I absolutely do - but this is not enabled by merely dispelling prejudice towards non-hegemonic language and myths about child development. There is a lot more for both individuals and collective society to navigate. The article below provides a good overview of the ethics and rights surrounding this subject. Of particular interest as case studies would be multilingual countries, which the article says provide "many examples of clashes between individual and collective language rights."

http://www.policyinnovations.org/ideas/commentary/data/000162

Anecdotally, my answer to each of your three questions is no. Nor have I been ever made to feel that my native language was "backwards and obsolete and worthless." This is speaking as a longtime expatriate though, which markedly diverges from the immigrant experience with regard to language aqcuisition.

Still, expats speaking their native language in a foreign setting can't be that much of a phenomenologically different experience. Or am I overlooking some significant difference?

Strangely, the only negative remarks I've encountered speaking my native language is in...my native country, when I make slight colloquial and other kinds of linguistic mistakes, due to growing up abroad. (I speak it well enough not to be mistaken for a foreigner, so the possibility of racism in these negative experiences is not a factor.) That's a totally different thing from what you're asking, although perhaps it is somewhat connected? To be criticised by your ethnic peers for not having retained your language perfectly? In any case, it shows how much of a power dynamic and ideology the mere act of speaking a language well (or not well enough) conveys, which immigrants could probably relate to.

P. Claus — April 3, 2013

My rather thick accent (Dutch/Flemish) is often mistaken for German. Over the years, I have grown weary of the replies in touristy German and/or silly questions it tends to generate. I should be carrying a whip in my purse, so I can validate that stupid stereotype that, yes, baby, I must be a dominatrix. That being said, since I am the only one speaking it, my husband being a native Californian, I gave up trying to teach it to my children when they started to correct me in English around the age of four or five.

Anonymous — April 3, 2013

I find it quite amusing that the author of this lovely graffiti, has yet to master the English language hirself. If we fail to automatically correct the atrocious grammar, the message is incoherent.

Danni — April 4, 2013

Pft, I would trade my ability to speak 3 languages at near native level for the ability to speak in "standart American" instead of my non-area specific foreign accent in English. It's possible that the very possibility of passing your accent to your kids (even if it IS very small) can prevent people from using their own language at home. And yes, this is because the States as a culture either hates or generally excludes people it sees as foreigners, all of the rosy "nation of the imigrants" propaganda notwithstanding. I understand WHY I do not generaly use my other languages and that one language is not better then the other, but understanding and hating the situation itself can't free you from all of the negativity (or clueless "we are so liberal" attempts you get from people trying to be culturally sensitive you get.

And I still feel like I should finish with "sorry for my English"... Oh well...

Lunad — April 4, 2013

The continuation of this, of course, is that later generations lament a lost cultural resource and attempt to recreate it. Sometimes, like Yiddish or Gaelic, it is difficult to even find native speakers to learn from. Other times, it's just the problem of trying to learn a language as an adult.

Albert — April 5, 2013

This is not only an American pattern. I speak a minority language native to the northern part of the Netherlands/Germany (Frisian), but I mostly just speak it to my parents and a few friends as I live in a city outside of the Frisian area. Still, if people hear me speak it, I get comments of how Frisians are so antisocial, speaking their own language to each other at parties. It is seen as a backward non-language, which in turn gives Frisians a feeling that they have to protect it proudly and at any cost.

As I'm mostly speaking Dutch in my daily university life, I have gradually lost my thick Frisian accent. When my family hears me talk Dutch, they often comment on my 'posh' accent.

I find it frustrating that language signals cultural belonging to such an extent that people will judge you on it, no matter what.

amar Duggal — April 9, 2013

"I’m sure that these parents truly believe that speaking only English to their children will give them an edge, though the reverse is true."

NO, it is untrue, even in nations not with English as main language are preparing for the next generation's language, which is English. Moreover take an example of Indian languages , most of them are broken form of one another. 21st century human is comfortable blending in, than standing out. That is no indication of any slavery. It is style of living that has been changing very fast specially with then internet becoming the next name of the game as far system is concerned, So if the system requires or encourages English being the main language, than that's what is going to happen. More over, why do we want humans to be identified with just a language, more focus needs to be on style of living. And that is being dictated with the internet as well. So let the dust fall where it falls. Focus on style and consequences of the style adopted. ( just to update you India is more western than Europe !!!)

The Stigma Of Immigrant Languages — April 17, 2013

[...] By Guest Contributor Calvin N. Ho; originally published at Sociological Images [...]

doop hoop — April 29, 2013

as much as i think other languages are cool interesting i think the world would prosper with a universal language.

Are you Illiterate in Your Native Tongue? A Look at Cultural Stigmatisation and Language | Listen & Learn AUS Blog — April 6, 2015

[…] a result of these factors, studies have shown in the US that immigrant languages typically don’t get passed on beyond the second […]

Is Spanish Hard To Learn? — July 17, 2020

[…] countries experience less violence or stigma towards bilingual […]