It’s a little known fact that the swastika, famously appropriated and perverted by the Nazis, is (or was) a symbol of good luck. Dating back to the Neolithic period, the symbol was frequently included in greetings and used as decoration. A 1917 ad for swastika jewelry, for example, called the symbol the “oldest cross” and explained it like this: “To the wearer of swastika will come from the four winds of heaven good luck, long life and prosperity.”

It’s a little known fact that the swastika, famously appropriated and perverted by the Nazis, is (or was) a symbol of good luck. Dating back to the Neolithic period, the symbol was frequently included in greetings and used as decoration. A 1917 ad for swastika jewelry, for example, called the symbol the “oldest cross” and explained it like this: “To the wearer of swastika will come from the four winds of heaven good luck, long life and prosperity.”

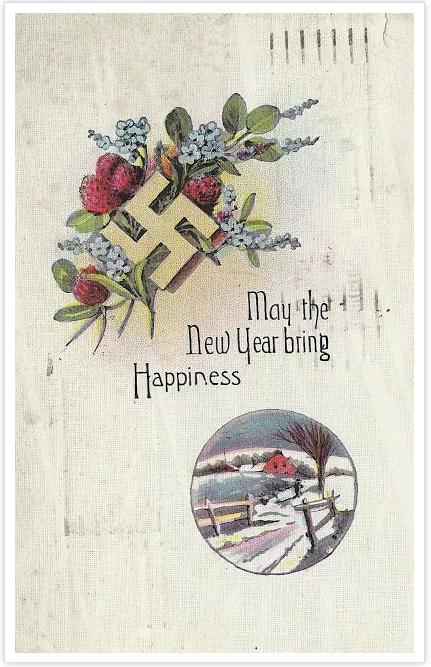

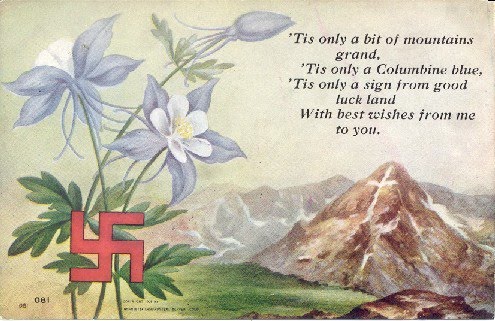

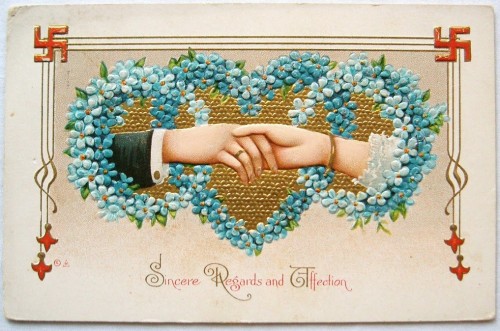

Here are some additional examples of the swastika being used to send hopeful messages to loved ones, found by Tom Megginson at The Ethical Adman along with the one above:

Happy New Year, everyone.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 12

Tom Megginson — January 1, 2013

Thanks for sharing, Lisa. I've had that first postcard in my collection for a number of years, but didn't share it until that old blogpost (which I recently recycled on Retronaut). Even though the symbol is not a bad thing in itself, in older use, I'm always worried about triggering friends with personal connections to the holocaust. Fortunately, nobody was upset.

Sam — January 1, 2013

I used to live in a town called Swastika in Ontario. During WWII, the government attempted to rename it Winston (as part of a similar campaign in the previous war, Berlin, Ontario, became Kitchener, Ontario). The townspeople fought the change, going so far as to take down the new signs, and issued their own campaign through signs like this: https://gs1.wac.edgecastcdn.net/8019B6/data.tumblr.com/IxbHdO34Daqe7a12RqKfCHg1_400.jpg

Norman Lewis — January 1, 2013

The Nazis didn't strictly pervert it. Because they considered it a symbol used by the people indigenous to indo-europe, they appropriated it to symbolise the 'ethnic groups' that they wanted to champion in that region. It was the supremecist and genocidal behaviour that then resulted in the symbol being associated with deranged and abusive fascistic behaviour. The way they used the symbol itself was not strictly what perverted it, it was the way they behaved whilst using the symbol.

Missmaia — January 1, 2013

The swastika is still used in Japan as a Buddhist symbol. It's a little alarming when you see a map covered with swastikas to mark the temples ("Nazis! Nazis everywhere!") but you get used to it.

Hbakker — January 2, 2013

The term "swa-stika" is Sanskrit. Every visitor to Bali will see many swastika symbols at the entrances to family compounds and homes. In a program on Adolph Hitler on public TV I saw the Celtic swastika that was at the altar at the Roman Catholic Church that young Adolph attended. He sang in the choir and was very impressed by the religious ceremonies. Charles Sanders Peirce wrote that every sign is arbitrary and contextual. What the sign stands for is a matter of context. The horrors of WWII have made us view the swastika as a horrible thing because to many of us it represents the worst cruelties of the Nazi regime, especially the atrocious death camps and concentration-work camps. But anything can be perverted. Sociologists must always be willing to take the larger view. That is why I believe a comparative-historical sociological imagination is very valuable. For me it has been especially important to see the world religions from a contextual and historical perspective. We tend to see a specific religion only on the basis of our own immediate phenomenological reality in our own lifeworld. But all the world religions have very complex histories.

Entaro — January 2, 2013

As other commenters have pointed out, iconographic knowledge regarding this ancient eastern symbol is not uncommon in the rest of the world. Perhaps it is telling that Dr Wade's first sentence begins with 'it's a little known fact' when it instead it should start 'in contemporary US culture'. An unusual omission and unconscious display of bias in this otherwise excellent blog, one I find puzzling given the lens sociology lends to one's imagination.

xurinye — January 2, 2013

One of our symbols here in the Basque country is a curvaceous kind of swastika. We actually predate the indo-european, but I guess we adopted it at some point (even before the Roman invasion).

It is called "lauburu", meaning four heads, and it has become one of our national symbols:

https://www.google.es/search?q=lauburu&hl=eu&tbo=u&tbm=isch&source=univ&sa=X&ei=YavkUL6VEoyShgf20oCYBg&ved=0CD8QsAQ&biw=1920&bih=979

pkin — January 2, 2013

I believe Lindbergh had a swastica (hey iOS autocorrects with a "c" and won't suggest a "k") on the onside of his propeller cap when he flew across the Atlantic.

(And I fixed my disqus issues)

brigidkeely — January 3, 2013

There was a very short period of time in the USA where swastikas were popular building decoration choices. This ended abruptly with the Nazi's use of the swastika. A lot of buildings that already had swastikas replaced them, covered them over, or painted them so suddenly they were rows of small boxes. There is a former synagogue near us decorated with swastikas. The remaining buildings with swastikas are stunning little time capsules, reminders of a brief moment when the swastika was becoming very popular and then suddenly became a symbol of horror.