Cross-posted at Family Inequality and The Atlantic.

The problem of income inequality often gets forgotten in conversations about biological clocks.

The dilemma that couples face as they consider having children at older ages is worth dwelling on, and I wouldn’t take that away from Judith Shulevitz’s essay in the New Republic, “How Older Parenthood Will Upend American Society,” which has sparked commentary from Katie Roiphe, Hanna Rosin, Ross Douthat, and Parade, among many others.

The story is an old one — about the health risks of older parenting and the implications of falling fertility rates for an aging population — even though some of the facts are new. But two points need more attention. First, the overall consequences of the trend toward older parenting are on balance positive, both for women’s equality and for children’s health. And second, social-class inequality is a pressing — and growing — problem in children’s health, and one that is too easily lost in the biological-clock debate.

Older mothers

First, we need to distinguish between the average age of birth parents on the one hand versus the number born at advanced parental ages on the other. As Shulevitz notes, the average age of a first-time mother in the U.S. is now 25. Health-wise, assuming she births the rest of her (small) brood before about age 35, that’s perfect.

Consider two measures of child well-being according to their mothers’ age at birth. First, infant mortality:

Health prospects for children improve as women (and their partners) increase their education and incomes, and improve their health behaviors, into their 30s. Beyond that, the health risks start accumulating, weighing against the socioeconomic factors, and the danger increases.

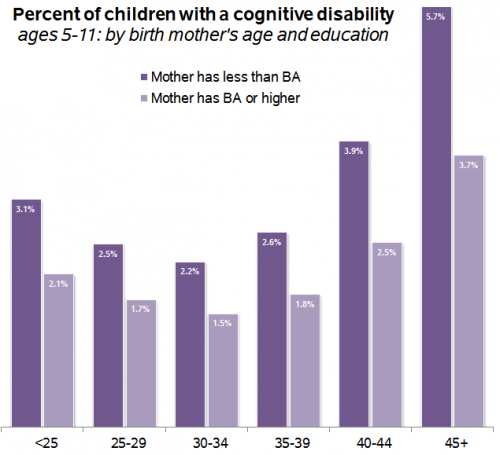

Second, here is the rate of cognitive disability among children according to the age of their mothers at birth, showing a very similar pattern:

Again, the lowest risks are to those born when their parents are in their early 30s, a pattern that holds when I control for education, income, race/ethnicity, gender, and child’s age.

When mothers older than age 40 give birth, which accounted for 3 percent of births in 2011, the risks clearly are increased, and Shulevitz’s story is highly relevant. But, at least in terms of mortality and cognitive disability, an average parental age in the late 20s and early 30s is not only not a problem, it’s ideal.

Unequal health

But the second figure above hints at another problem — inequality in the health of parents and children. On that purple chart, a college graduate in her early 40s has the same risk as a non-graduate in her late 20s. And the social-class gap increases with age. Why is the rate of cognitive disabilities so much higher for the children of older mothers who did not finish college? It’s not because of their biological clocks or genetic mutations, but because of the health of the women giving birth.

For healthy, wealthy older women, the issue of aging eggs and genetic mutations from fathers’ run-down sperm factories are more pressing than it is for the majority of parents, who have not graduated college.

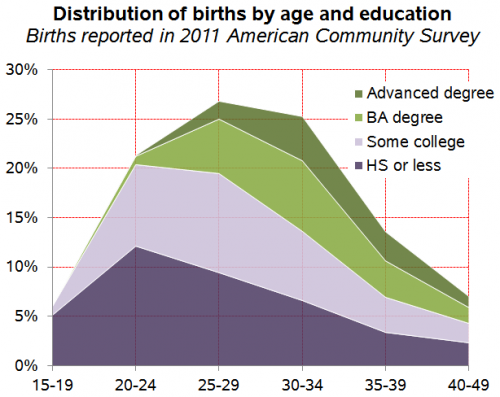

If you look at the distribution of women having babies by age and education, it’s clear that the older-parent phenomenon is disproportionately about more-educated women. (I calculated these from the American Community Survey, because age-by-education is not available in the CDC numbers, so they are a little different.)

Most of the less-educated mothers are giving birth in their 20s, and a bigger share of the high-age births are to women who’ve graduated college — most of them married and financially better off. But women without college degrees still make up more than half of those having babies after age 35, and the risks their children face have more to do with high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and other health conditions than with genetic or epigenetic mutations. Preterm births, low birth-weight, and birth complications are major causes of developmental disabilities, and they occur most often among mothers with their own health problems.

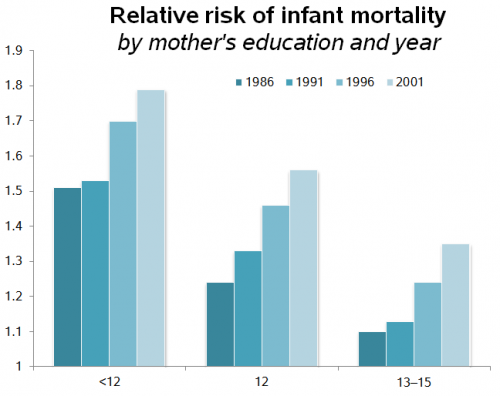

Most distressing, the effects of educational (and income) inequality on children’s health have been increasing. Here are the relative odds of infant mortality by maternal education, from 1986 to 2001, from a study in Pediatrics. (This compares the odds to college graduates within each year, so anything over 1.0 means the group has a higher risk than college graduates.)

This inequality is absent from Shulevitz’s essay and most of the commentary about it. She writes, of the social pressure mothers like her feel as they age, “Once again, technology has given us the chance to lead our lives in the proper sequence: education, then work, then financial stability, then children” — with no consideration of the 66 percent of people who have reached their early 30s with less than a four-year college degree. For the vast majority of that group, the sequence Shulevitz describes is not relevant.

In fact, if Shulevitz had considered economic inequality, she might not have been quite as worried about advancing parental age. When she worries that a 35-year-old mother has a life expectancy of just 46 more years — years to be a mother to her child — the table she consulted applies to the whole population. She should breathe a little bit easier: Among 40-year-old white college graduates women are expected to live an average extra five years compared with those who have a high school education only.

When it comes to parents’ age versus social class, the challenges are not either/or. We should be concerned about both. But addressing the health problems of parents — especially mothers — with less than a college degree and below-average incomes is the more pressing issue — both for potential lives saved or improved and for social equality.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Comments 21

Anna — January 3, 2013

"Why is the rate of cognitive disabilities so much higher for the

children of older mothers who did not finish college? It’s not because

of their biological clocks or genetic mutations, but because of the

health of the women giving birth."

Educated women are also more likely to be able to afford getting screening for cognitive (and other) disabilities in fetuses, and may elect (and can afford) to terminate their pregnancy after a diagnosis of disability. This influences these numbers.

"If you look at the distribution of women having babies by age and

education, it’s clear that the older-parent phenomenon is

disproportionately about more-educated women."

Isn't it important to bring up here that older women having babies are mostly the ones who can afford expensive fertility treatments? That technological intervention plays a significant role here? I don't know the relevant statistics about older parents, but if it weren't for fertility treatments (and surrogate motherhood, and egg-freezing which we will see more the results of more in the next decade or so), by and large we wouldn't even have an older-MOTHER phenomenon.

Older mothers are not exactly rare; we all know of women who naturally conceived up to their late 40's (although these women usually had their first child(ren) at a more biologically regular age, as it is far harder to concieve naturally for the first time at this age). But without technological intervention, there probably still wouldn't be enough older mothers for it to register as a phenomenon.

Jennifer — January 3, 2013

I was suspicious of the Shulevitz article because of her huge error in saying that "The risk that a pregnancy will yield a trisomy rises from 2–3 percent when a woman is in her twenties to 30 percent when a woman is in her forties." Um, no. http://www.fetalultrasound.com/online/text/31-014.htm

She writes a lot about the potential effect of older fathers, too, which is a nice change from the seemingly obsessive focus on mothers one often finds.

Guest — January 3, 2013

Where's the fun in guilting women without BAs or who live in poverty? Much more fun to go after the ones who already feel bad about daring to get older every year.

Yrro Simyarin — January 3, 2013

Can we separate the effects of smoking/drug abuse (correlated with low income) from the effects of insufficient medical care (also correlated with low income) in these graphs? Or is the claim that we should see no difference between the two cases?

Lisa G — January 3, 2013

I'm curious about the source of the data for the chart "Percent of Children with a Cognitive Disability." What counts as a cognitive disability? It says that the ages of the children are 5-11 - does that mean the data come from school records of students in special education? Because if that's the case, then there is a lot more to it than the effects of poverty caused by lower levels of education.

Racial minority students and students who do not speak English at home are diagnosed with cognitive disabilities and behavioral disorders much more frequently than other students. There have been studies done to figure out exactly why this happens; it certainly is related to poverty, but also probably has to do with the cultural expectations of schools not always matching up with the students' home cultures. Students who have not mastered English often get diagnosed with cognitive disabilities because they do poorly on IQ tests and other evaluations that are only administered in English. Students with behavioral problems are sometimes given diagnoses of cognitive disabilities just so that they will be put in a class with a higher teacher to student ratio.

So I would be skeptical of using data from school special education records because it seems like it would be impossible to tease out the root cause. The consequences of the confluence of low-education, poverty, and (racial or linguistic) minority status on children's cognitive abilities and school success is incredibly complex and trying to pin it to just once cause would be over-simplifying.

To find out more on this topic, check out: "Why are So Many Minority Students in Special Education?: Understanding Race and Disability in Schools" by Harry and Klingner. The authors conducted longitudinal case studies of black and hispanic students who received special education services. There is also a companion volume, which includes the results of the individual case studies, entitled, "Case Studies of Minority Student Placement in Special Education."

anon — January 3, 2013

Is it not even worth addressing that part of the correlation between childhood cognitive disability and maternal educational attainment might be explained by the heritability of intelligence?

MH — January 3, 2013

Does that graph from Pediatrics actually show that infant mortality steadily increased from 1986 to 2001??

Elena — January 4, 2013

Is it poverty or is it the lack of access to proper healthcare? It would be interesting to see if any developed country with universal healthcare displays this correlation.

Poverty Poses a Bigger Risk to Pregnancy Than Age » Sociological Images | digitalnews2000 — January 6, 2013

[...] on thesocietypages.org Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in [...]

links for thought, May 2013 — June 21, 2013

[...] “Poverty Poses a Bigger Risk to Pregnancy Than Age,” Sociological Images, Philip N. Cohen [...]

samnems — January 28, 2020

I am in very last stages to movie and produce a film documentary

to elevate cognizance on Female Genital Mutilation, display screen it in 3 East African

nations and work with more activists to paintings closer to ending Female Genital Mutilation in East Africa. Here

is the hyperlink to the marketing campaign page for the

film documentary i mean it doesnt count number what coler we are. Are that subjects is who we're and that we are all created equal.greatpeople.me And permit me inform that the human beings out there which can be racists, you have to be ashamed of yourselves because irrespective of what race or religion, we're all of the same ExpressHR.

Ben Stones — November 13, 2021

Hi, Dreat Article! I appreciate your efforts you did to explore about the poverty poses a bigger risk to pregnancy than age. Well done.

Thank you.

Beatrice Jordan — November 17, 2021

Greetings,

I read your article and found it informative and very helpful. Keep writing such an amazing content.

Regards

AmazingAir

philip watmor — November 17, 2021

According to me a lady's pinnacle conceptive years are between the late teenagers and late 20s. By age 30, richness (the capacity to get pregnant) begins to decrease. This decrease turns out to be more fast once you arrive at your mid-30s. By 45, fruitfulness has declined such a lot of that getting pregnant normally is far-fetched for most ladies.

pimp my kitchen