I often find myself bemused at our insistence on using sex (i.e., male or female) as the defining thing that describes our sexual orientation. We are homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual, right? These words supposedly mean that we are sexually attracted to the same sex, the other sex, or both. Right?

No! Not by a long shot! Essentially no one is attracted to men, for example, no matter what their sexual orientation. I’m straight and female, but I am attracted to a very, very, very small subset of men. I’m generally only attracted to men within a certain age range, with kind faces (I find the chiseled look a bit intimidating); also, I prefer them to be relatively clean. If I can add non-physical characteristics, then being aggressive with buddies or rude to waitstaff or prone to jealousy are all turn-offs, as are certain politics. I’ll stop here. Suffice to say, suggesting that I’m attracted to men is a vast overstatement. Sexual orientation, as we think of it, simply doesn’t describe my proclivities. I suppose this is true for most of us.

I was reminded of this idea when I came across an OK Cupid post. Christian Rudder drew on the profiles of over 250,000 heterosexual users, discovering that a large percentage of them had (positive) sexual experiences with people of the same sex, or wanted to (source).

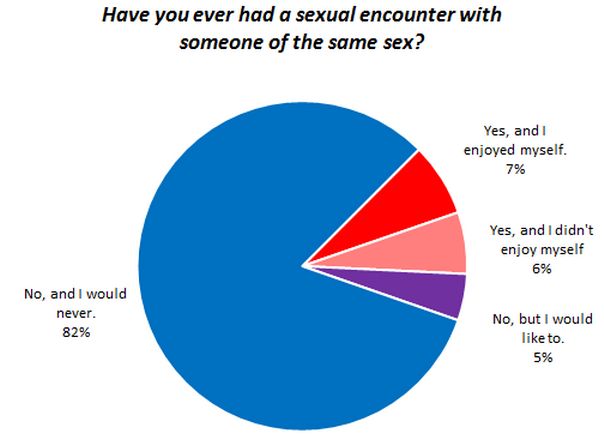

Thirteen percent of self-identified straight men have had a sexual encounter with another man. Seven percent of them enjoyed it. Another 5% haven’t had the pleasure, but they would like to.

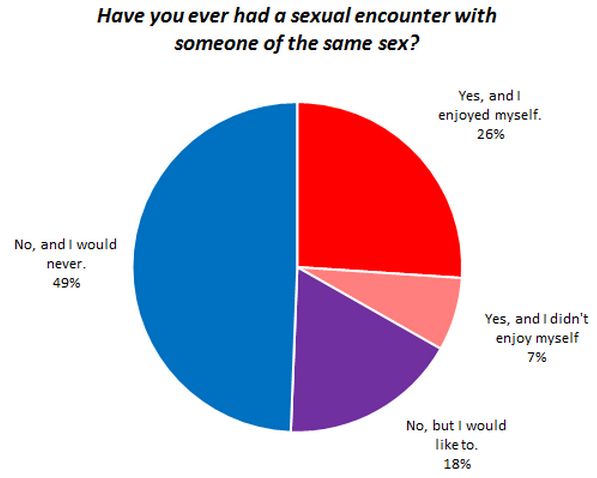

Significantly more self-identified straight women, 33%, have had a sexual encounter with another woman. Twenty-six percent of them enjoyed it. Another 18% haven’t, but they would like to. Less than half reported that they hadn’t and figured they never would.

Reported sexual orientation, then, simply doesn’t map perfectly onto desires or behaviors, in addition to failing to capture the full complexity of our sexualities.

For more of OK Cupid’s data, see our posts on the racial politics of dating, what women want, how attractiveness matters, age, gender, and the shape of the dating pool, older women want more sex, and the lies love-seekers tell.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 55

Lindsey Bieda — October 24, 2011

This is one of the things I think about fairly often. We often represent sexual orientation as a finite set of labels and you fall into one category or another. However, these labels don't accurately represent the type of people one may be interested in, so I attempted to create a way to still gather this sort of information while stepping away from the concept of strict labels.

I came up with this: http://rarlindseysmash.com/projects/triangleselectors/v2/

Which is still considered a rather incomplete and imperfect way of collecting this data, but to me it feels slightly better than labels. There's a dimensionality there and a consideration that people are not so clear cut.

Yrro Simyarin — October 24, 2011

It's a general categorization. As long as we don't treat the division between labels as hard lines, we're still going to need something to describe the statistical clumps and thresholds.

And we do, generally, have labels for the more specific preferences you mention. You can be a leg man, or a boob man... someone who likes shy girls, or nerds, tomboys or redheads... it all falls under some variant of heterosexual, though. Even if you're on the 95% girls and that one guy you met at boyscout camp edge of the cluster.

I tend to look at it as, what are your thresholds for finding some physical attraction if personalities really matched. With a few limited allowances for age or extreme physical condition, I can think of few limits to what women I could be attracted to. But I have a really hard time even envisioning a man whom I would want physical contact with, beyond just affection and friendship. As the size of these two groups shift based on your personal preference, you end up closer to one pole or another... it's a gradient... but the people are one end are still going to have more in common with their preferences than someone on the other end, so it's useful to group them together. You may *prefer* men without a chiseled jaw... but if the love of your life happened to have one, you'd probably live with it.

Philip Cohen — October 24, 2011

Great point, Lisa. I also believe this means studies of sexual orientation -- its patterns, distribution, causes, etc. -- are all plagued by the problem of an ill-defined dependent variable.

Barbara — October 24, 2011

Well, sexual orientation might capture your inability to come out to yourself as non-straight, when you identify as straight but like a small minority of men.

Anonymous — October 24, 2011

Excellent point. Since we can't tell someone's sex most of the time, I've always wondered why it's so important when it comes to sexual identity. Personally I'm far more attracted to certain facial features and mannerisms than I am to certain gender expressions, and I suspect that many others are too - still we don't go around and call for example Hugh Hefner a "blonde-sexual"

Forsythia — October 24, 2011

Gender expression also fails to map to either gender or orientation.

fannie — October 24, 2011

I share your bemusement, Lisa. As a lesbian, I'm certainly not attracted to everyone in the group "woman."

To take a US-centric view, I would speculate that our tendency to categorize ourselves by sexual orientation is a result of (a) the medicalization of homosexuality in the late 19th century, (b) LGB advocates' resulting push to remove homosexuality from the DSM, and (c) LGB advocates' (understandable and necessary) legal/political framing of "homosexual" as a category of person that is innate, relatively unchangeable, and discriminated against.

Theophile Escargot — October 24, 2011

I am very, very skeptical about this data since it comes from the OKcupid datablog here:

http://blog.okcupid.com/index.php/gay-sex-vs-straight-sex/

Firstly, this means it's not gathered anonymously. This comes from a series of mostly-public compatibility questions that OKcupid members use to search for matches (you can opt to keep a particular question private, but most people don't).

So, people are answering these questions with a view to attracting a partner with their answers. It could be that some men think disclosing a bisexual experience will put off potential partners, while some women think disclosing a bisexual experience will attract potential partners.

Secondly, the userbase of OKcupid isn't necessarily anything like a representative sample of the wider population. Not everyone uses dating sites. Some people will prefer paid dating sites to free ones like OKcupid.

BFR — October 24, 2011

I agree that sexual orientation is inadequate for fully describing people's actual sexual (and romantic and aesthetic, for that matter) interests. On the other hand, interpreting sexual orientation labels as purely descriptive is also pretty simplistic. For many people, especially people who aren't straight (because straight is seen as default), words like "gay" and "lesbian" don't just describe sexual interests but also cultural identities. People create communities around these words -- as well as "queer," "pan[sexual]," etc.

Incidentally, OkCupid doesn't allow people to choose "queer" or other identity labels, other than "gay," "straight," or "bisexual," to describe themselves. This is limiting BOTH because sexual orientation labels are inadequate descriptors of sexual interests, AND because it doesn't allow people to use the identities they would use to make friends and form communities in real life.

Anonymous — October 24, 2011

I agree that our definitions of sexual orientations have problems, but I don't think these graphs prove anything about it. Perceiving a contradiction between being straight and having had a sexual experience (even an enjoyable one!) with a member of the same sex strikes me as promoting a very narrow, purity-driven idea of straightness. After all, all it takes is one single same-sex experience -- or just willingness to admit a little curiosity about it -- to put someone in the supposedly scandalous portion of the graph. Is someone who's a 0.5 on the Kinsey scale necessarily better described as bisexual or queer than straight? Certainly the idea of heterosexuality as requiring purity is a major cultural narrative -- consider all the guys who write to Dan Savage asking things like "will accidentally touching another guy's junk turn me gay?" -- but it seems like something we should be analyzing, not something we should be deploying.

Maybe you had fun with your one same-sex fling, but want to settle down with an different-sex partner. Maybe you wanted to be open to possibilities, but after giving it a try you decided it wasn't for you. Maybe you've always been pretty securely attracted to different-sex people, but you're still a bit curious and don't want to entirely close the door. Maybe you're interested in same-sex sex, but not same-sex serious romance, and it's serious romance that you're seeking on a dating site.

Fernando — October 24, 2011

A person might one day find him/herself attracted to a specific type of men/women that they didn't before. That's being attracted to a specific gender. Say, right now I like specific types of women but tomorrow I just might be attracted to an even broader share of women for one reason or another.

Anonymous — October 24, 2011

This is a hard thing for me to talk about dispassionately - but I certainly think about it a lot! It's true that my own sexual orientation is firmly at odds with my understanding of sex and gender. These categories are problematic, definitely. On the other hand, they're very important political and social identities.

Basically, while "gay" isn't a perfect word, I feel like I don't want to undo this particular social construct until I can't get fired for where I fall within it. Does that make sense? Ideally, I'd love people to have a nuanced view of attraction, one that doesn't focus entirely on sex/gender... but first, I'd like to get to the point where my partner and I don't have to hope for a queer-friendly landlord to find a place to live.

Young queers that I talk to these days - some of them, anyway - say that the labels aren't important, and they don't want to have to claim a particular identity. They'll love who they love, and that's all there is to it. I'm not sure how well that works in practice (if you have a same-sex partner, you are ascribed the status "gay"), but if it does, all power to 'em. In my life, that hasn't been how it works. I'm a social being and in many social situations my gayness is right at the forefront of everyone's mind, whether I like it or not. Being able to see myself as a lesbian, identify with queer history, find community with other lesbians and other queers - that's how I get on with life in a world that seems to be otherwise full of people who wish I would, at best, pretend not to exist.

In addition, for many of us, being gay/bi/lesbian is such an important status - claiming the label and living openly takes courage and is both freeing and frightening - that to hear it distilled into "this is all about attraction" is difficult. Being a lesbian - openly claiming that identity - brings a lot more with it than sex with women. Like, say, boatloads of discrimination in everyday life.

From a methodological perspective, I think it's important to understand that attraction and identity are *different*. Attraction is sometimes fluid, is definitely not either/or. But those problematic either/or identities are also very powerful forces in our lives, and I don't want to dismiss or ignore them because they don't perfectly reflect underlying reality.

I think this post would be just as valid if it were about racial categories... is anyone arguing that we should stop paying attention to them just because the underlying reality of race is far more complex than the construct?

Anonymous — October 25, 2011

I think you've got good and bad points here. Of course, the current ways of defining orientation are based mostly on gender binaries and people's sex lives. They're rigid and narrow, and don't take into account more than "what bits does this person have, who do they sleep with most often." But your example doesn't really seem to address that. Saying a woman is "straight" doesn't mean she is "attracted to every man," but "is attracted exclusively or mostly exclusively to people who are men." If you're "only attracted to men with these physical features and these personality traits," you're still "only attracted to men." (This is taking into account widely accepted definitions, not more nuanced understandings of personal orientation) I've rarely come across people who actually think straight people are sexually attracted to everyone of the opposite gender. That's not what the label really means. It is worth noting that a lot of people DO apply those same assumptions to gay and bisexual people ("wait, so if you're gay, does that mean you have a crush on me?" or "bisexual=anything that moves"), but that's rooted more in homophobia than misunderstanding of what "gay" means.

Ferridder — October 25, 2011

Thirteen percent of self-identified straight men have had a sexual encounter with another man. FIFTY-FOUR percent of them enjoyed it.

One percent is not a percentage point. /petpeeve

Gilbert P. — October 25, 2011

Is there no hepcat anymore prepared to mouth the orthodoxy: that sexuality is genetically determined. Is everyone here saying it's a lifestyle choice? OK, I get nuance, but we are coming down pretty heavily on the side of weakly determined preference here.

Guest — October 25, 2011

While I very much agree with the idea of this article, a dating site's unscientific survey is certainly not the data to be backing it up with. I'd love to see these concepts explored further by some proper research.

Barbara — October 25, 2011

It's useful politically. See the following excerpt from an article about the recent UN resolution on sexual orientation-based rights.

"Although several countries claimed a supposed lack of a definition of sexual orientation in international law as a reason for their opposition, countries such as Rwanda firmly rejected this saying: "Take my word, a human group need not be legally defined to be the victim of executions and massacres as those that target their members have [already] previously defined [them]. Rwanda has also had this bitter experience sixteen years ago. It is for this that the Delegation of Rwanda will vote for this amendment and calls on other delegations to do likewise."

Homophobes define sexual orientation very strongly. If we don't do the same there's a risk that their definitions will prevail.

I often find that it's easier for bisexuals to identify as straight than gay, because of the negative stigma attached to all the non-straight labels. Many people who don't want to be labeled, that's because they are not straight. Most straight people have no problem being labeled, not as much as non-straight do. Guess why?!?! ;)

Galatea Lies — October 25, 2011

"Sexual orientation, as we think of it, simply doesn’t describe my proclivities. I suppose this is true for most of us."

Beware, beware, beware! Your lived experience describes no-one but you; at best it describes straight-identified socially-conscious women of your age, race, and class, maybe. The data you present doesn't support your speculations, either.

That said, the data itself isn't especially compelling. After all, it comes from a dating site, in which presumably everyone is presenting themselves in what they perceive to be a sexy light. For men, this means under-reporting homosexual encounters; for women, over-reporting.

Janis Hasir Bing — October 27, 2011

Meh. I think it's easy to say that when you fall under heterosexuality's characteristics. The day being with someone of the same sex becomes devoid of stigma, maybe we'll let go of our queer identities more easily but for now, it's a survival issue, as a minority group. Subcultures matter, mostly because they're a support system in the face of oppression.

Mädchenmannschaft » Blog Archive » Mitlesen und mitmachen – kurz Notiertes in dieser Woche — October 28, 2011

[...] Society Pages stellen die Frage, wie aussagekräftig das Konzept der “sexuellen Orientierung” überhaupt ist, um [...]

Judith Avory Faucette — October 29, 2011

Too true. I'm doing a session at a convention next year called "Workshopping Your Sexual Orientation" that focuses on how individuals can figure out sexual orientation aside from, or in addition to, gender. For me, as a genderqueer person, I found it helpful to think about sexual orientation more broadly because it's literally impossible for me to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, or straight (all these terms require that the subject of the term be either male or female). I identify as queer, but that isn't actually very useful as an organizing principle for whom I'm attracted to. I use other traits instead.

Sunday Hustle 27/10/11 « Girls Are Made From Pepsi — October 29, 2011

[...] Do we need words like straight, bisexual or homosexual? Hell to the no, says Lisa Wade. Features pie charts! (The Society Pages) [...]

daniel — October 30, 2011

Sexual orientation depends of the posture. When kids the grandfather put you on his prick, when younger the churchman sucks yr prick or yr conin, when adult, all depend from it: if you bend, someone gives you by Ass.

Life, give way to fucking... je je

Gerpderp — November 5, 2011

I think it's pretty pointless to try to derive anything meaningful from this survey question. The answers are so concrete and extreme, that anyone who hasn't had a homosexual encounter must choose between "no, and I hate the idea completely," implying homophobia and disgust, or "no, but i identify at least somewhat as homosexual." Anyone who has had a homosexual encounter either loved it or disliked it. These are all unnatural dichotomies.

The options don't leave space for answers like "no, I haven't, I'm not opposed to the idea, but it's just never happened," "no, I am celibate," "yes, but it wasn't particularly serious, more of an experiment."

Bella Blithely » Blog Archive » Threads from the Web | 25 November 2011 — November 25, 2011

[...] asks how useful is the concept of sexual orientation? Something to think [...]

Richard Gadsden — January 16, 2012

Interesting that you choose to see "heterosexual" as meaning who you are attracted to.

The way I would ask the question if I had my druthers is this:

Have you ever experienced any sexual attraction whatsoever to a person that you identified at that time as being male? (tickbox)

Have you ever experienced any sexual attraction whatsoever to a person that you identified at that time as being female? (tickbox)

If you don't tick either box, then you're asexual, if you tick both, then you're normal (aka bisexual), and if you tick just one, then you're one of those boring monosexuals and you have to work out your own gender to work out which one you are.

Incidentally, is it just me that finds it interesting that we divide monosexuals up as heterosexual/homosexual rather than gynosexual/androsexual?

Identifying lesbian women with straight men and straight women with gay men would certainly change the way we understand sexuality.