I recently came across the guideline that was used to calculate how much money was to be paid out to the victims of the attacks on September 11. This was a fund that was set up by the US government partly because of the scale and the unprecedented nature of the September 11th attacks and partly to diminish the amount of lawsuits that the airlines would receive.

According to the New York Times article it goes as follows:

1. Economic loss.

2. Set amounts for pain and suffering: $250,000, plus $100,000 for each surviving spouse and child.

3. Subtract any life insurance paid.

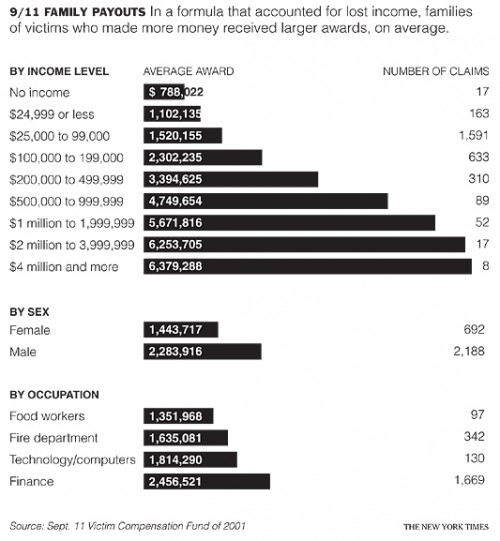

Along with the rubric, The Times also included a chart that showed the amount of payouts that took place as of 2007:

Putting a price on a life is already a difficult concept to parse through. So I am not taken back that the people in charge actually found a price for each of the victims (some compensation had to be made for those individuals who now found themselves without the sole or part-earner in the household).

What I am taken back by is the stratification of how the payouts were dispersed. Who is to say a person makes no income is worth less than a person who makes 4 million and up? Who is to say females are worth less than males? Who is to say that food workers are worth less than individuals who work in finance?

I get the aspect that a person who was a blue collar worker or someone of no income will get less of a payout than a white collar worker or someone who was making $4 million based on the first guideline “economic loss”. But even that argument doesn’t hold much weight as that the food worker might be the next JK Rowling or that person of no income could be the next Bill Gates. Why would it not account for ability not yet realized? We are a meritocratic republic aren’t we?!

Even in a national tragedy like the attacks on September 11 we can’t seem to follow through on the belief that we are a classless society. These payouts are, unfortunately, the reality of the extreme stratification that we hide when we, as a society, claim that we are classless.

AFTER THE JUMP: STEVE GRIMES RESPONDS TO THE COMMENTS THREAD…

—————————–

Steve Grimes has his Master of Arts degree in sociology from St. John’s University in New York, is currently seeking a Master of Science degree in media studies from CUNY Brooklyn College, and plans to be enrolled in a Ph.D. program within the next two years. He is, at the moment, engrossed in all things cultural studies and his blog, TimelyDonut, is an avenue to express that.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Comments 42

Ricky — February 22, 2011

"Why would it not account for ability not yet realized? We are a meritocratic republic aren’t we?!"

Seriously? Ok, I get it now. Gwen and Lisa are just punking us with the whole guest blogger thing, no one could actually be that daft.

Rick — February 22, 2011

This whole thing was a waste of taxpayer money. That is why you have private insurance. I suppose we could have given the equivalent of the same policy we give to the families of soldiers killed on duty back then. It was around $250K. Even that is excessive. All are equal in the military. The insurance on a General is the same as a private.

Ein — February 22, 2011

Payouts for adult victims in these sorts of cases are determined in part by examining the amount of money people are expected to earn in their respective lifetimes. Thus, the attorney of a person who dies in a high-paying job will be argue that he or she would have continued to make at least the salary that they earned when he or she died, as well as arguing for pay increases the decedent would have experienced had they continued. It's not fair, of course, as this system tends to favor the families of higher wage earners, but that is the prevailing system for claims of this nature. An exception is when a state has a cap on payouts for wrongful death claims against the government.

George — February 22, 2011

I completely agree. Personally, I think it's a bad policy precedent for the government to give out any money for events like this. If 3000 people died it's not so expensive to give in to the public's sympathy, but what if it had been an attack in which many more had died.

If something must be given let it be the same amount, or limit it to the poor. The richer people should have had the means and good sense to purchase life insurance. They could easily have been victims of any number of more mundane tragedies.

The justification that the airlines had to worry about lawsuits is very sad. There is an extreme level of litigiousness in the US that needs to be addressed.

Basiorana — February 22, 2011

I understand that in these cases, they're going on lost income, and the death of a 50 year old person who makes no money, while tragic, is not going to cost the family as much as the same person who was the sole breadwinner.

We should consider everyone equal, but still consider that some people have more to support than others. A single mother with three children who was a food service worker should warrant more money for her children than a married childless man in his 50s who makes twice as much but whose wife makes an equal salary and can easily support herself.

I wonder, though, what they would do with someone like me-- a recent college graduate who if I enter my field eventually will make probably 40-60K/year but who is currently NOT in my field and making 10K? It's easy to estimate how much a 40, 50, etc year old will make in their life. How do you estimate the worth of an underemployed person?

MPS — February 22, 2011

I think the rationale for such payouts is not so much to compensate for suffering (how could you put a price on that?) so much as to compensate for lost future income. In this sense the payouts are very progressive, significantly over-valuing low-wage workers relative higher-wave workers. I think this is perfectly sensible.

T — February 22, 2011

So, for all of those above who think the 9/11 Victim's Fund is a bad policy...

The idea was to short-circuit the standard tort process. The result would have been tying up the court system for perhaps decades, bankrupting the airlines and their insurers long *before* all of the cases were settled, and crippling the United States airline infrastructure -- unless it was taken over by the government to continue operation. And we all know that the better (more expensive) lawyer someone has, the better the payout...

The government fully recognized that these payouts would not be as large as potentially emerging from litigation... but they were Guaranteed! and Quick!

I'm not saying this is the most wonderful solution... it ain't. It cost the taxpayers something like $8 billion. Not ideal.

But was there really much of an option?

Scott — February 22, 2011

"Why would it not account for ability not yet realized? We are a meritocratic republic aren’t we?!"

1) It does. It empirically determines that if they're working in food service, they'll be working in food service for the rest of their life. It's the assumption that ties the whole meritocratic illusion together- That the story of the American Dream and rags to riches is nothing more than the rarity of class motility in all societies put into legend. It's like winning the lottery or being struck by lightning- people still buy tickets and people still avoid walking outside during rainstorms because the big win or loss is great marketing.

2) If the government had allowed the victims to sue the airlines, the payout would have come from the same place- the taxpayer. Assuming airlines can be sued is predicated on the incorrect assumption that airlines are any more liquid than farmers.

3) The stratification of payouts matches the stratification of income. Women are worth less than Men because Women make less than Men.

Tort damages are also determined based on "what will make the victim's estate whole", not "what value do we place on a life". If you break somebody's neck and commit them to paraplegia for the rest of their life, the damages they're entitled to are a combination of their pain, suffering, loss of consortium (normal human interactions/sex), lost earnings, medical costs, lost potential future earnings (determined on empirical evidence), and other things.

In another sense, Tort damages are "the amount of money you can pay this victim to shut up". Particularly in settlements, if a victim thinks they can get $3 million in court, it's pretty safe to assume they'll take $2.5 million and change to get the money in their pocket faster. Particularly if your partner worked in food service, you may actually need to pay the "expedition fee" of settling for less (because, let's face it, you may go bankrupt before the proceeding is over). If your wife was making $3 million as a top legal counsel to the WTO, you could maybe afford to press for as much money as they'll pay you to keep it out of court.

AnaMarie — February 22, 2011

Granted, I am not a sociologist, but this is the first time I have ever heard anyone state that we are a classless society. The appeal of US society has not been the supposed classlessness, like this author apparently assumes, but the ease of which one is able to rise through the classes. Ease may not be the correct word here, but class mobility is what has always been possible in the US, though difficult and highly unlikely, and why so many have historically wanted to live the "American dream".

This seems to be a good compromise between the ideas of how much was (s)he worth (#1), and what does his/her family need (#2). No society that has any meritocratic aspect can be classless, and therefore the assumption can be made that someone who was making a lot of money will continue to make a lot of money, and someone in a low-wage industry will continue to remain in such a position. We may all have unlimited potential if we manage to find the right opportunity at the right time, but this is not dealing with what may have been. It's dealing with the hardship directly caused due to this tragedy.

Steve — February 22, 2011

I just wanted to follow up on the post.

First, I can see how many are misinterpreting what I was trying to bring across in the post. Much of my approach in the post was tongue-in-cheek. It was one of my earlier postings and I have since learned that the use of sarcasm isn't the best way to bring across a point than can be somewhat complex.

I was not criticizing the practical nature of the payouts. I also was not criticizing whether it was a good use of tax payer money. As many have noted one of the main reasons these payments went down was to avoid lawsuits which could be argued is a good thing. Furthermore, there was the practical issue of replacing income. So, it is understood that a food worker would get paid less than a finance worker because of the different incomes (if that was part of the rubric).

What I was trying to get to was how we view class and equality in our society and how we generally have contradictory viewpoints to those concepts.

So one hand we are a society based on class when we sell the "American Dream". That anyone can achieve "success" if they try hard enough because we are all made equal and have equal chances.

On another hand, we deny class exists whenever someone tries to show the great inequality (and the reasons for that inequality) that our society holds. Class has literally become a four letter word. Whenever that inequality is shown the individuals who would like to deny inequality exists scream "class war" as if class antagonism does not exist.

A good example of how we pick and choose when and how to talk about class is how the recent austerity measures are being introduced by our politicians; paraphrasing: "families all over the country are tightening their belt, so the government has to also". As if we are all in this together equally, when it is simply not the case (i.e. the attack on Unions; tax breaks for the rich).

So this post was to give a representation of our contradictions and how we pick and choose when and how we talk about class. On one hand, the food worker is created equal with everyone else and he has an equal chance to become a finance worker in our supposedly meritocratic society (the "greatness" of our society is literally based on this). However, on the other hand (even though his supposed potential has not have been realized with his death) he is not paid equally with the finance worker. The payouts (should) represent that contradiction.

I hope my follow up comments clean some of the misinterpretations up.

T — February 22, 2011

Since many people have already brought up the notion in tort law of "making one whole" (or in the case of death, making the estate whole), it's probably worth doing some of the math for those of you who have missed it. So, why does the $62,000/year person get so much less than the $750,000/year person?

Well, they don't... in terms proportional terms. Assuming income remains the same (and using the median award figure), the $62k individual's estate received the equivalent of 25.5 years of income (actually more like 39 years since these settlements were tax free); while the $750k individual's estate received 6.3 years of income (or around 10 years tax free).

So, the disbursements were about 4:1 for these two groups.... a VERY progressive disbursement schedule!!!! Very.

Also, the question, "Who is to say females are worth less than males?" is ridiculous. Not the question of a social scientist. It's the question of a pundit or politician... It ignores REALLY obvious issues at play. Who worked in the World Trade Center? What industries? What was the gender distribution? What was the income distribution for these? 74% of the claims were by folks in finance... How many of the 166 individuals with $500,000+ income were women? Do you think this might skew the averages??

Michael Knapp — February 22, 2011

While I appreciate your follow up comments, and find them much more considered than the original article, you failed to address what I found to be the central misconception there, evident in your questions, "Who is to say a person makes no income is worth less than a person who makes 4 million and up? Who is to say females are worth less than males? Who is to say that food workers are worth less than individuals who work in finance?". The payouts are not valuing persons, they are compensating lost expected income. There is no evidence here to suggest that anyone, save perhaps yourself, is "putting a price on life."

Rob — February 22, 2011

What I found striking was that only about a quarter of the 9/11 victims are women. It's obviously due to the masculine domination in the world of finance, but it's also something we're not reminded of a lot, as the victims are usually portrayed as a pure representation of America.

Greg — February 27, 2011

Thank you, Bishop, for the apology. I apologize if I overreacted, but you seemed to be reading something into my post. I think I had a different take on Rob's than you did.

"Finance" is a big umbrella term. I wonder if there is the same imbalance with retirement planners, for example, versus traders. I only know two people who work in securities--both women--but that is just personal experience and I am outside the industry.

Bradley Sanford — September 17, 2025

Not only focusing on the feeling of speed, speedstars also offers many different competition modes to challenge players.