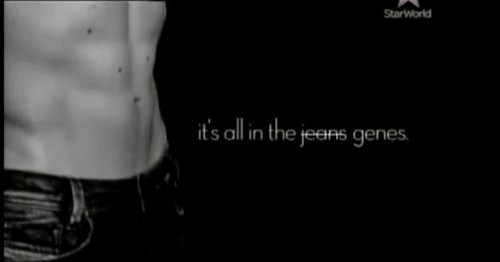

“You can’t be taught the skills to model, because first and foremost, skill doesn’t matter. It’s all in the jeans genes.”

So notes a shirtless man, a self-described “male mannequin” in commercials for Next Top Model in Vietnam:

My sociological knee-jerk reaction is to point to the ways in which models’ labor is deliberately rendered invisible, masking performance as mere appearance, in much the same way social categories are naturalized to appear like states of being instead of products of social organization — think gender, ethnicity, class, and yes, beauty.

As concerns the category of beauty, there is considerable work involved in pulling it off. Like retail service workers, models do “aesthetic labor,” as documented by sociologists Elizabeth Wissinger and Joanne Entwistle and more recently by Christine Williams and Catherine Connell. Aesthetic labor is the work of manipulating one’s physique and personality to embody a company brand. In the modeling market, some people easily have that physique, as the shirtless guy claims to have, but most models have to fight for it, and they’re fighting against the clock of aging. If they don’t have to work for cut abs and narrow hips, they most likely still feel compelled to work at it, given the rampant uncertainties facing them in their daily grinds of auditions and rejections. All of this work gets carefully tucked behind the scenes of fashion and beauty images — a clandestine world NTM purports to expose for voyeuristic consumers around the world.

But instead of exposing it, the NTM franchise caricatures it. In the American version, Tyra Banks insists that effort is everything, and she axes candidates left and right because they didn’t “want it badly enough.” She just didn’t work hard at it, goes the usual dismissal, or she lacked the determination to keep smiling when Jay Manuel told her that her face is weird. It’s not that you’ve got the wrong look, the show tells contestants, but that you didn’t put in the work to get the right one. NTM sticks close to an individualistic ethos: if you fail, it’s because you lacked the individual effort needed to succeed.

Success in any culture industry is a mix of both hard work and the luck of being the “right” contender at the right moment, which is somewhat arbitrarily decided in any given fashion season. Saying that success is “all in the genes” renders the “look” into a natural state of being, when like all culture industries, modeling is a complex social production.

Saying it’s all in the jeans is also pretty funny. Let’s not overlook this guy’s self-deprecating humor: here’s a man surrendering himself (and his manhood) to the whims and preferences of fashion, an industry widely believed to be controlled by women and gay men. In other ads he mocks his talent and wryly notes the biggest hazard in his line of work: wearing leopard print g-strings (to say nothing of occupational challenges like the precarious nature of freelance labor, the lack of health and retirement benefits, or the unpaid labor of castings and magazine shoots). What’s most striking about this guy and his seductive black-and-white commercial is not the sociological back story, it’s his own silliness. He’s playing on the ironic gap between social expectations of masculinity and the realities of being featured as a passive visual object. We probably wouldn’t be so charmed if the commercial featured a young woman laughing about her job title: “I’m a professional model!” We’d probably roll our eyes. The source of that silliness—unequal cultural expectations about the display value of men and women—is as problematic as it is good fodder for comedy.

Ashley Mears is a former model and current Assistant Professor of sociology at Boston University who is doing fantastic work on the modeling industry. In her book, Pricing Beauty: Value in the Fashion Modeling World (UC Berkeley Press), she examines the production of value in fashion modeling markets.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Comments 7

Fernando — February 7, 2011

Anybody thought of Zoolander when he said the "really really good looking" line?

m — February 7, 2011

Come to think if it, why are all these reality shows about striving for a thankless job? Mears already noted the the contitions for models are less than ideal, and then there are the so called "prizes" of similar professions on other shows: we have singers, who just like models have very unstable careers, chefs, who have one of the more stressful jobs in modern service society, designers, hairdressers, various shows about starting your own company... All of these are careers that pay very poorly except for those who manage to get to the very top, and the reality shows in no way guarantee that that is what's going to happen.

I know that they are mostly doing this for the drama anyway, but since they've managed to squeeze drama out of airports, that may not explain the entire picture.

Essence Emme — February 8, 2011

Excellent posting, Ashley! I was a Soc major and actually never truly considered how beauty goes right along with those other tricky social constructions. Thank you!