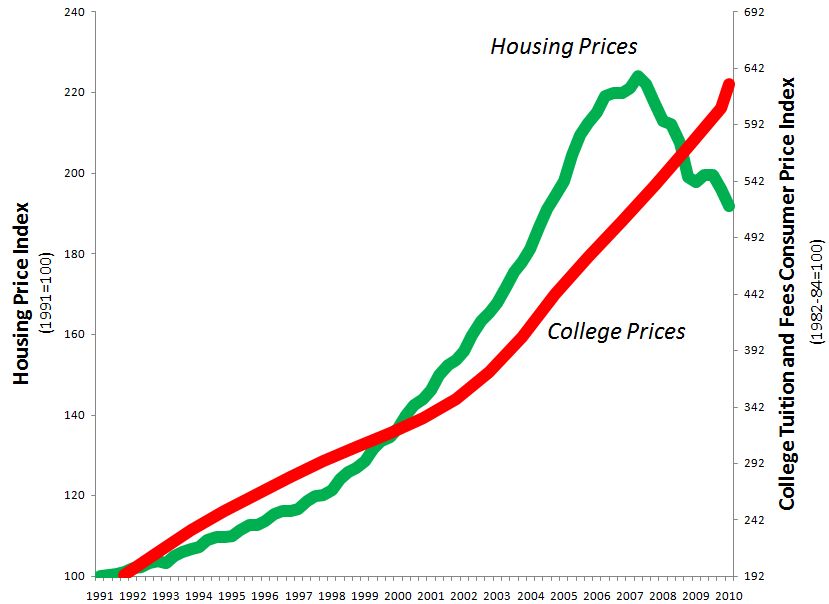

At Family Inequality, Philip Cohen argues that the rising cost of higher education may be directly related to the cost of homes. In the figure below, he shows that housing prices and college tuition have risen in tandem, at least until recently:

Cohen doesn’t chalk this up to simple inflation influencing both trends. Instead, he argues…

…the connection between home wealth and college attendance was sometimes direct, as when experts advised parents to use home equity loans to send their kids to college (advice you don’t hear so much these days). But even without home equity loans, the wealth stored in middle-class homes — for most such families their largest asset — underwrote millions of college educations. I guess you could say the federal policies promoting homeownership were big boons for the higher education industry, not just the GIs and mostly-white suburbanites who landed inside the picket fences.

That is, rising home prices meant that people who could afford those homes could pay more for their children’s college educations. The price of college, then, could afford to increase without pricing out all those middle- and upper-class families.

Cohen asks for ideas about what will happen now that home prices have dipped and the cost of higher education continues to rise.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 20

Perseus — September 24, 2010

I wonder how or if this affects degree saturation in the labor markets. It seems to me that the incentive for adults to get their degrees has pushed education and experience requirements for employment much higher than the usual standards. To get that experience or higher education requires more income as prices go up, allowing for better opportunities for the upper class, while people in the middle class who have degrees yet can't use them are forced to go unemployed or underemployed in this recession. And the lower class, they're already in a rough state as it is.

Meg — September 24, 2010

Or perhaps there is a third factor such as easy credit? The more credit people can easily get, the more they can pay for things, the more prices can go up. Both housing and higher education are strongly linked to credit, and in particular what many people consider "good credit" (i.e. a very socially approved use of credit) and large amounts of it.

But with houses you have foreclosures which can start bringing down prices even in non-foreclosed homes. With student loans, it's trickier since you can't resell your degree even if the loans were bankruptable. And with the pressure to go to college so great because of the job market, simply not going to college isn't seen as an option for many. I think because of those factors, it will take longer before college prices start to drop (if they do).

Scapino — September 24, 2010

I'd posit that rising (skyrocketing) home values and rising educations costs happened independently, and the fact that both were happening simultaneously is what caused the home-as-a-piggy-bank advice to become popular.

If car values had skyrocketed, or Pokemon cards or POGs, or whatever, people would be told to leverage those to pay for college. I'm with Perseus, college tuition is tied more to the sky-high demand for degrees than to people's ability to pay. If you don't mind going into debt, student loans aren't hard to get for financially solvent people who are well-off enough to have lots of home equity.

That said; cool post and an interesting hypothesis.

Lynne Skysong — September 24, 2010

Is this graph adjusted for inflation? If not, I'd be interested to see how that compares.

DORU — September 24, 2010

This graph is terrible, and suggests nothing. The y-intercepts have been manipulated in order to get a suggestive lay-over, the two graphs are scaled differently(not that the units are meaningful anyway), and the date to which the 'tuition index' is normalized to isn't even included on the graph! That suggests he also picked a convenient time interval to present as well. The only use this graph could be put to is as a showpiece in how not to make a graph. I could make a similar graph linking tuition to global average temperature.

b — September 24, 2010

This kinda seems tenuous at best, especially given that the two lines have different Y-axes! Did they actually run any kind of statistics that would show that there's a statistically significant correlation, or did they just lay these graphs on top of each other and say "Hey look, the slopes are kinds similar... sometimes"???

Their explanation for this connection isn't very good, either. It seems like the availability of financial aid probably has a lot more to do with rising costs than the fact that people who can afford expensive houses can also afford expensive colleges - because the fact is, most homeowners can't afford college without any aid! But now colleges can charge higher tuition without making it look like they're trying to keep the poor out, so they do. I'm not saying that the reasoning is entirely that cynical, but let's say federal financial aid dried up tomorrow magically - I'm betting a lot of schools (though certainly not all) would not be comfortable having a freshman class next year made up entirely of upper-middle-class students. They'd have to do something to make sure that at least some of the poorer students who qualify for admission can afford to attend.

AR+ — September 24, 2010

A far simpler and I think more correct explanation is simply that the market for both of those products is heavily manipulated by the government in ways that tend to increase price, hence they both rise in price at a rate which outpaces inflation. The same could be said of the medical industry, another major expense that both has a history of rising prices and severe intervention of the type that raises prices.

anonymouse — September 25, 2010

Actually, a superficial look at the graph makes it look like housing prices and tuition are driven by independent factors. Housing prices have fallen, but nominal tuition is continuing to rise at the same rate, which suggests that rising housing prices were not the reason for above-inflation tuition increases.

I wonder if the well-above-inflation rise in upper-end incomes is a better explanation of tuition increases. People from upper income brackets are the ones paying the sticker price; everyone else is paying a lower price through grants or (more commonly) subsidized credit. If this is the explanation we'd expect the dollar value of subsidies to rise in tandem with nominal tuition. I don't know whether that's true.

The college premium has also been rising at a rate significantly above inflation, which may be increasing students' (and their parents') willingness to pay. Increased demand -> higher prices.

Nikitin — December 19, 2024

Your article addresses a very serious situation. Education expenses and house expenses are both very high in today's era. I completely agree with you. However, the things that are very essential, life becomes difficult without them. I have found a solution to this; I only use very necessary things in my house. For sleeping, I use a folding mattress. This mattress is easy to handle and affordable as well. Similarly, I have enrolled my children in a nearby college. This way, a lot of savings are made.