Gender gaps are everywhere. When we use the term, most people immediately think of gender wage gaps. But, because we perceive gender as a kind of omni-salient feature of identity, gender gaps are measured everywhere. Gender gaps refer to discrepancies between men and women in status, opportunities, attitudes, demonstrated abilities, and more. A great deal of research focuses on gender gaps because they are understood to be the products of social, not biological, engineering. Gender gaps are so pervasive that, each year, the World Economic Forum produces a report on the topic: “The Global Gender Gap Report.”

I first thought about this idea after reading some work by Virginia Rutter on this issue (here and here) and discussing them with her. When you look for them, gender gaps seem to be almost everywhere. As gender equality became something understood as having to do with just about every element of the human experience, we’ve been chipping away at all sorts of forms of gender inequality. And yet, as Virginia Rutter points out, we have yet to see gender convergence on all manner of measures. Indeed, progress on many measures has slowed, halted, or taken steps in the opposite direction, prompting some to label the gender revolution “stalled.” And in many cases, the “stall” starts right around 1980. For instance, Paula England showed that though the percentage of women employed in the U.S. has grown significantly since the 1960s, that progress starts to slow in the 1980s. Similarly, in the 1970s a great deal of progress was made in desegregating fields of study in college. But, by the early 1980s, about all the change that has been made had been made already. Changes in the men’s and women’s median wages have shown an incredibly persistent gender gap.

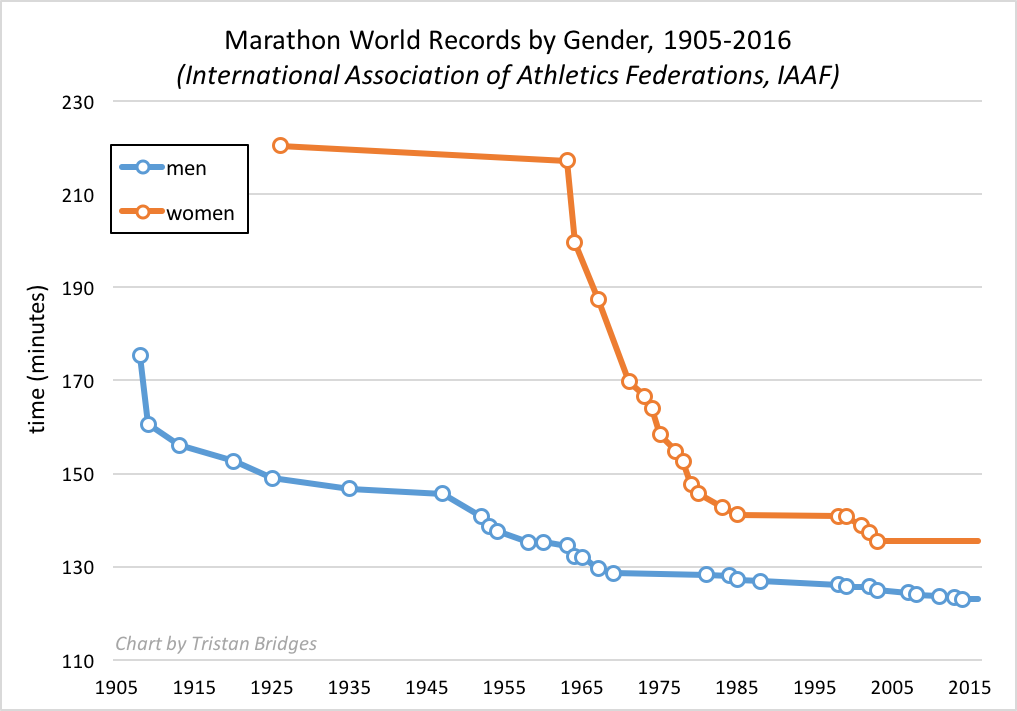

A set of gender gaps often used to discuss inherent differences between men and women are gaps in athletic performance – particularly in events in which we can achieve some kind of objective measure of athleticism. In Lisa Wade and Myra Marx Ferree’s Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions, they use the marathon as an example of how much society can engineer and exaggerate gender gaps. They chart world record times for women and men in the marathon over a century. I reproduced their chart below using IAAF data (below).

In 1963, an American woman, Merry Lepper, ran a world recording breaking marathon at 3 hours, 37 minutes, and 7 seconds. That same year, the world record was broken among men at 2 hours, 14 minutes, and 28 seconds. His time was more than 80 minutes faster than hers! The gender gap in marathon records was enormous. A gap still exists today, but the story told by the graph is one of convergence. And yet, I keep thinking about Virginia Rutter’s focus on the gap itself. I ran the numbers on world record progressions for a whole collection of track and field races for women and men. Wade and Ferree’s use of the marathon is probably the best example because the convergence is so stark. But, the stall in progress for every race I charted was the same: incredible progress is made right through about 1980 and then progress stalls and a stubborn gap remains.

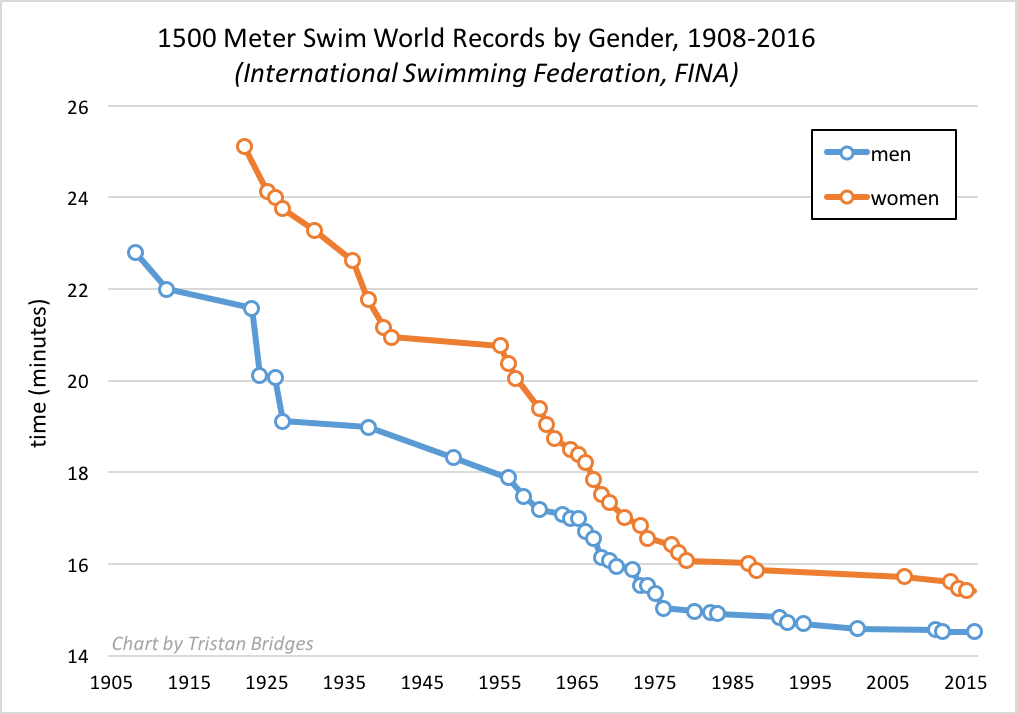

Just for fun, I thought about considering other sports to see if gender gaps converged in similar ways. Below is the world record progression for men and women in a distance swimming event – the 1500-meter swim.

The story for the gender gap in the 1500-meter swim is a bit different. The gender gap was smaller to begin with and was primarily closed in the 1950s and early 60s. Both men and women continued to clock world record swims between the mid-1950s and 1980 and then progress toward faster times stalled out for both men and women at around that time.

One way to read these two charts is to suggest that technological innovations and improvements in the science of sports training meant that we came closer to achieving, possibly, the pinnacle of human abilities through the 1980s. At some point, you might imagine, we simply bumped up against what is biologically possible for the human body to accomplish. The remaining gap between women and men, you might suggest, is natural. Here’s where I get stuck… What if all these gaps are related to one another? There’s no biological reason that women’s entry into the labor force should have stalled at basically the same time as progress toward gender integration in college majors, all while women’s incredible gender convergence in all manner of athletic pursuits seemed to suddenly lose steam. If all of these things are connected, it’s for social, not biological reasons.

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.

Comments 16

Alastair J Roberts — January 23, 2017

Women are quite different from men on several criteria relevant to their labour force participation. Even in the most egalitarian countries—and often especially in the most egalitarian countries, where people are freer to follow their preferences without suffering significant disadvantage—women cluster to the caring professions, while men dominate things like construction and engineering. They are always more physically and typically more psychologically invested in the task of child-rearing than men. On average, they tend to be more concerned about the domestic environment than men. They have a much greater preference for certain types of work than men, forms of work that play to gendered interests that are witnessed from the earliest stages of childhood, before kids even know what gender is, gendered toy and play interests that can also be seen in other primate species. Their motivations tend to differ from men. They tend to be rather more concerned about 'work-life balance' than men, in large part because they are less likely to invest so much of their self-fulfilment in their work.

Much, much more could be mentioned. However, the issue is that women's entry into the labour force, especially when measured relative to men's, will tend to be shaped and limited by a host of factors. At a certain point, unless the shape of the economy changes markedly (as it might be doing through the automation of male-dominated construction, haulage, factory, and other such jobs), clear differences will exist, because men and women are different in their interests and, to a lesser extent, in their aptitudes and abilities.

Even if both men and women were active in the work force at the same rate, we would still expect to see large differences in the ratio of men and women in particular fields of work, differences that would take an entirely predictable shape. We would expect to see significant differences in work hours, overtime, willingness to sacrifice for career progression, part time versus full time work, participation in physically dangerous work, participation in people-oriented versus thing-oriented work (even in a single field or profession), distance travelled to work, etc., etc.

When it comes to sports, there are a number of reasons why things plateaued for women in many areas of athletics in the 1980s. One of those reasons is because it is much harder for women to get away with using anabolic/androgenic steroids nowadays (and, yes, there is a good reason why women might take androgenic steroids to increase their performance). We should expect some more of the gap to be closed in certain fields as women with hyperandrogenism and transwomen are allowed to compete (look at the podium for the women's 800m at Rio for an example of the potential dominance of certain sports by such women), but these cases really demonstrate the biological factors that are at play. If the differences between male and female biology weren't an issue, there is no reason why three women with exceedingly rare intersex conditions would all be standing on the podium after the 800m race.

Although we can still marginally push the right tail of the distribution curve to find ever more extreme outliers, it is currently a game of diminishing returns in most men's and women's athletic sports (until something like the CRISPR revolution hits, perhaps). The great recent advances in the records for both the women's marathon and the 1500m freestyle are the work of two women: Paula Radcliffe and Katie Ledecky. Such athletes, like Usain Bolt in the men's 100m, are the outliers of the outliers, streets ahead of the rest of the field at their best.

However, when dealing with an outlier of outliers, it is important to keep in mind where the rest of the pack lies if we are going to predict further significant breakthroughs. For instance, not only does Paula Radcliffe hold the top three fastest women's marathon times in history, the nearest women to her is three minutes off her pace. The same isn't true for the men's marathon, where there are over sixty times and dozens of runners represented in the same time range of the best time, with the majority of those times having occurred in the past five years.

And, it should be noted, even though Radcliffe is three minutes faster than any other women before or since, her time doesn't even come anywhere near to making the top 3,000 times for men, and, I would suspect, not even the top 5,000. When we are dealing with extreme right tails, this is the sort of thing to expect. Much as there are thousands of six foot high men for every one woman of that height, so, when it comes to the strongest and fastest people in society, men will be overwhelmingly represented at the extreme.

The problem with treating the gender gap as something that should just be expected to narrow indefinitely is that we must take into account the distribution curves of the relevant traits. For instance, as David Puts has observed:

Taken together with differences on a wide range of other metrics (height, muscle mass, grip strength, etc.), the disparity between the average man and woman is stark across many measures and particularly striking on certain ones. These disparities will effect the sort of distribution of men and women that we should expect at the extreme right tail of activities related to the traits in question. Unless you can account for the vast majority of these differences in average strength, height, muscularity, adipose tissue, and other bodily traits by sexism, the differences in athletic achievement would seem to have a fairly natural explanation for anyone who is open to the biological facts.

These differences will be more pronounced in some areas than in others. For instance, the strongest women's weightlifter in the highest women's weight class, Tatiana Kashirina (over 108kg), can't lift as much as the strongest man in the 69kg weight class, Liao Hui (both Kashirina and Liao Hui have doping offences, so their records should be assessed accordingly), and less than 74% of the strongest male weightlifter.

When we start to reach the peaks of human potential, selecting for the outliers of the outliers, the variation in the field can swiftly decrease. Even slight genetic differences on average can lead to significant differences in the representation of groups at the extremes. For instance, why have 72 of the 72 athletes in the finals of the last nine Olympic Games 100m races had African and almost all West African ancestry, while mostly competing for Western countries? Why have the quests for the great white sprinter come up empty handed? Was there just a sudden white flight from the most prestigious athletics event, or are other factors at play?

fork — February 5, 2017

" The remaining gap between women and men, you might suggest, is natural. "

We tend to be quite oblivious (or actively in denial) to the many ways we treat girls and boys differently. Here's but one study that shows how the gap is still about nurture, not nature:

"This study examined gender bias in mothers’ expectations about their infants’ motor development. Mothers of 11-month-old infants estimated their babies’ crawling ability, crawling attempts, and motor decisions in a novel locomotor task—crawling down steep and shallow slopes. Mothers of girls underestimated their performance and mothers of boys overestimated their performance. Mothers’ gender bias had no basis in fact. When we tested the infants in the same slope task moments after mothers’ provided their ratings, girls and boys showed identical levels of motor performance."

Carl Armstrong Jr. — February 19, 2017

One thing that comes to mind about records like running marathons and extreme levels of competition like that for women is exercise induced amenorrhea. While not necessarily a permanent condition, many female athletes experience this, essentially sacrificing "fertility" for performance. The level of performance required, the training needed, and the investment in time to move women from "normal" to record-level often has biological consequences. Things like reducing body fat and boosting muscle mass to compete with similarly proportioned males have different consequences for women, like amenorrhea, which also have social, emotional, cultural, and other consequences.

Perhaps one of the changes you should consider isn't necessarily technical innovation or sports science but the social acceptability of childlessness as well as delayed fertility in social terms. This is probably a consideration in women's participation in the workforce as well as the "glass ceiling" limitation for women vis-a-vis employer concern about losing women to the hearth and home.

Gender Gaps and the Stalled Gender Revolution – Inequality by (Interior) Design — February 19, 2017

[…] Originally posted at Sociological Images. […]

A Year in Review and Best of 2017 – Inequality by (Interior) Design Edition – Inequality by (Interior) Design — January 9, 2018

[…] Images often drew from materials I’d been putting together for bits of the textbook, like my post on the curious alignment and stall associated with gender gaps across a variety of different […]

Gender equality at home takes a hit when children arrive | DJG Blogger — August 8, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little […]

Gender equality at home takes a hit when children arrive – Headlines — August 8, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little […]

Gender equality at home takes a hit when children arrive – The Daily Angle — August 8, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little […]

Gender equality at home takes a hit when children arrive – QuickAcesss — August 10, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little […]

How having children impacts gender equality at home - — August 13, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status, and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little […]

Gender equality at home takes a hit when children arrive - — August 16, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little […]

Gender Equality at Home Can Take a Hit When Children Arrive #genderequity | Girls Speak Out™ — August 29, 2019

[…] the changes in opportunities, status and attitudes that were closing the gap between men and women began to slow. Since the mid-1990s, there’s been little change.Gender equality at home among heterosexual […]