Historian Molly Worthen is fighting tyranny, specifically the “tyranny of feelings” and the muddle it creates. We don’t realize that our thinking has been enslaved by this tyranny, but alas, we now speak its language. Case in point:

“Personally, I feel like Bernie Sanders is too idealistic,” a Yale student explained to a reporter in Florida.

Why the “linguistic hedging” as Worthen calls it? Why couldn’t the kid just say, “Sanders is too idealistic”? You might think the difference is minor, or perhaps the speaker is reluctant to assert an opinion as though it were fact. Worthen disagrees.

“I feel like” is not a harmless tic. . . . The phrase says a great deal about our muddled ideas about reason, emotion and argument — a muddle that has political consequences.

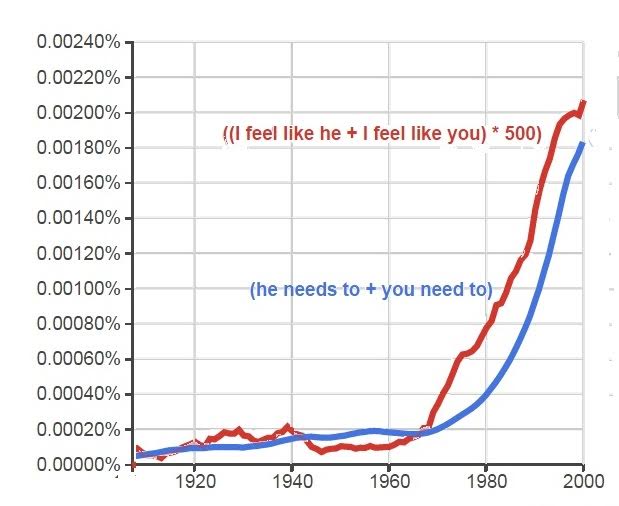

The phrase “I feel like” is part of a more general evolution in American culture. We think less in terms of morality – society’s standards of right and wrong – and more in terms individual psychological well-being. The shift from “I think” to “I feel like” echoes an earlier linguistic trend when we gave up terms like “should” or “ought to” in favor of “needs to.” To say, “Kayden, you should be quiet and settle down,” invokes external social rules of morality. But, “Kayden, you need to settle down,” refers to his internal, psychological needs. Be quiet not because it’s good for others but because it’s good for you.

Both “needs to” and “I feel like” began their rise in the late 1970s, but Worthen finds the latter more insidious. “I feel like” defeats rational discussion. You can argue with what someone says about the facts. You can’t argue with what they say about how they feel. Worthen is asserting a clear cause and effect. She quotes Orwell: “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” She has no evidence of this causal relationship, but she cites some linguists who agree. She also quotes Mark Liberman, who is calmer about the whole thing. People know what you mean despite the hedging, just as they know that when you say, “I feel,” it means “I think,” and that your are not speaking about your actual emotions.

The more common “I feel like” becomes, the less importance we may attach to its literal meaning. “I feel like the emotions have long since been mostly bleached out of ‘feel that,’ ” …

Worthen disagrees. “When new verbal vices become old habits, their power to shape our thought does not diminish.”

“Vices” indeed. Her entire op-ed piece is a good example of the style of moral discourse that she says we have lost. Her stylistic preferences may have something to do with her scholarly ones – she studies conservative Christianity. No “needs to” for her. She closes her sermon with shoulds:

We should not “feel like.” We should argue rationally, feel deeply and take full responsibility for our interaction with the world.

——————————-

Originally posted at Montclair SocioBlog. Graph updated 5/11/16.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Comments 7

Jonathan — May 10, 2016

I strongly disagree with the notion that talking about feelings during debates about issues "halts argument in its tracks." That might be true if the receiver is uncomfortable with engaging with others' personal feelings. But the way to move these conversations forward is simple. You acknowledge someone's feelings and their validity, but you recognize that these are feelings and as such may be flawed.

Here's an example: class discussions about affirmative action inevitably lead to a white student bringing up reverse racism. They will say something like, "I feel like black students have an advantage in college admissions." If we take Worthen's advice to heart, the response would be that the student's feelings are invalid and fallacious. Are we wrong to say that reverse racism is fallacious? Of course not. But denying the student's feelings about the matter accomplishes absolutely nothing and probably serves to degrade the conversation, since the student now feels invalidated and attacked. A better approach would be to acknowledge the student's feelings, analyze where these feelings come from (the student's personal context), and explain why their feelings don't match the reality that many students face (they possess invisible advantages). It's a fantastic opportunity to link the personal with the sociological, but it would have been missed if we merely dismissed the student's feelings and "addressed the facts."

This post and the op-ed both suggest that contemporary anxieties are the product of obsession with one's well-being and narcissistic tendencies. I vehemently disagree with this point of view and the arrogance from which it stems. If anxieties arise from a focus on the self, it is because people possess deep-seated insecurities and feelings of not being "good enough." It is completely wrongheaded to attribute anxieties to an obsession with "personal satisfaction." This is the epitome of victim blaming. As someone who suffers from mental illnesses, including severe anxiety, this brand of victim blaming angers me beyond belief.

Refusing to acknowledge the validity of others' feelings amounts to refusing to acknowledge of the validity of others' humanity and creates an atmosphere of shame about one's own feelings and fear about people's reactions to those feelings. Just because feelings are imperfect representations of reality doesn't mean they're invalid. We can't escape our feelings. Would you tell someone suffering from depression to just stop feeling sad? We can only deal with our and others' feelings as best we can. Perhaps "as best we can" means showing kindness and empathy while also comparing people's feelings to our larger reality and investigating where those feelings have deviated from the particular facts of this reality. Shame alienates and isolates, narrows the pool of potential participants in a conversation, and reduces the diversity of views contributed to the conversation.

You know what this critique of "I feel like," well, feels like? Critiques of young people's, particularly young women's, speech patterns, including excessive use of "like" and upspeak. Yeah, I say things like "I feel like" and "like" and use upspeak. A professor in undergrad once called me out for saying "I feel like." My interpretation of this interaction was not of someone focused on preserving rational discourse, but of someone keenly interested in sticking their nose in the air and telling me to get off their lawn. Why does this matter? Because older generations have been sticking their noses in the air about the kind of language younger generations use since time immemorial, justifying such hand wringing with all sorts of specious arguments.

I feel like folks should stop telling people how to talk and start listening a little more. Yeah, I said "I feel like." Yawn. Stop shaming people with alienating, unproductive semantic snobbery. In other words, embrace your humanity and others' humanity and don't be a horrible person. Why assume that debates over issues constitute a zero-sum game? We don't have to privilege feelings at the expense of facts or privilege facts at the expense of feelings. Both are interconnected and an integral part of human explorations of the reality we inhabit.

Also, since when does Sociological Images post veiled screeds about millennials and their "entitlement" and "narcissism"?

fork — May 11, 2016

Coincidentally, I just read this on the sexism and racism of criticisms of speech patterns. And I was also reminded of this post about how refusals are done (we don't just say no) and understood.

I feel like Worthen is just another geezer railing at the audacity of young women being the leaders in speech trends. And that her literal take on "I feel" is as dishonest as the male claims not to have understood refusals in the Mythcommunications post.

Woz — May 11, 2016

"She has no evidence of this causal relationship"

So you could say...this is something she feels to be true? And as such, I can't argue with her, because her argument is based on her feelings, and not any empirical evidence.

This argument is...slightly hypocritical.

Peter Sanderson — May 12, 2016

>>>“I feel like” defeats rational discussion. You can argue with what someone says about the facts. You can’t argue with what they say about how they feel.

Which I believe is the point entirely. "Personally, I feel like Bernie Sanders is too idealistic" distances the speaker from argument about whether or not Bernie Sanders is or is not idealistic,or even if he is _too_ idealistic.

This phraseology also head nods to the reality that other people might disagree with the speaker on either of these points, but more importantly that the speaker *isn't* trying to establish some fact about Bernie Sanders character or beliefs.

Consider also, if I were to say "This food is salty". Any response is about the food -- is it too salty? Is it saltier than last time? Should it be this salty? These are all absolutes.

Conversely, if I were to say "I feel like this food is too salty" then we can have a conversation about me and my experience of the food, and a conversation that does not need to consider the quality of the food or whether it is or is not salty.

I feel like this hedging on language by not using absolutes allows for freer and more earnest expression of perception and belief that allows for more open and honest dialog about eachother and ourselves, as opposed to falling into "Is not" "Is too!" arguments.

Lauren — May 13, 2016

Totally not surprising that men have no problem with this wording. As a woman, it diminishes how well my opinion is received if I hedge it; it's as if women's feelings are thought to be less reliable or something. Hmmmmmm.... It should be obvious that what I'm saying is what I think to be true because I am the one saying it. I shouldn't have to add that I think it to be true; that's redundant.