They hold the same amount of wealth.

We all know that wealth is unequally distributed in the US. But, the results of a new study by the Institute for Policy Studies, authored by Chuck Collins and Josh Hoxie, are still eye popping.

Collins and Hoxie find that the wealthiest 0.1 percent of US households, an estimated 115,000 households with a net worth starting at $20 million, own more than 20 percent of total US household wealth. That is up from 7 percent in the 1970s. This group owns approximately the same total wealth as the bottom 90 percent of US households.

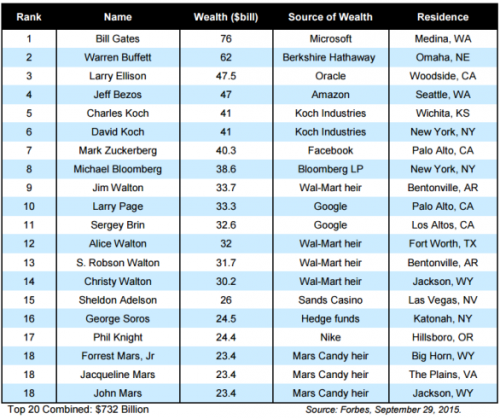

Moving up the wealth ladder, they calculate that the top 400 people—yes, people not households, each with a net worth starting at $1.7 billion, have more wealth than the bottom 61 percent of the US population, an estimated 70 million households or 194 million people.

Finally, we get to the top 20 people, those sitting at the pinnacle of the US wealth distribution. As the authors explain:

The wealthiest 20 individuals in the United States today hold more wealth than the bottom half of the U.S. population combined. These 20 super wealthy — a group small enough to fly together on one Gulfstream G650 private jet — have as much wealth as the 152 million people who live in the 57 million households that make up the bottom half of the U.S. population.

Although obvious, it is still worth emphasizing, as Collins and Hoxie do, that great wealth translates into great power, the power to shape economic policies. And, in a self-reinforcing cycle, the resulting policies, by design, create new opportunities for the wealthy to capture more wealth. Think: free trade agreements, privatization policies, tax policy, and labor and environmental laws and regulations.

Oh yes, also think presidential politics. As a New York Times study points out:

They are overwhelmingly white, rich, older and male . . . . Across a sprawling country, they reside in an archipelago of wealth, exclusive neighborhoods dotting a handful of cities and towns… Now they are deploying their vast wealth in the political arena, providing almost half of all the seed money raised to support Democratic and Republican presidential candidates. Just 158 families, along with companies they own or control, contributed $176 million in the first phase of the campaign, a New York Times investigation found (emphasis added).

And yet, one still hears some people say that class analysis has no role to play in explaining the dynamics of the US political economy. Makes you wonder who pays their salary.

Originally posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.

Comments 2

AG — December 9, 2015

So, what can we do about the influence of the wealthy?

There is an interesting paradox within campaign finance, reducing and limiting donations shifts the incentives of politicians and that shift isn't always in favor of "we the people". Unless reducing the influence of money doesn't give extra power to those that hold power independent of money, reducing the power of money will have harmful effects.

Assume that we limit campaigns and financing. Everyone gets equal air time and ad space in the real world:

Would the winner be the person that has the best ideas? Not necessarily, if the audience is susceptible to fear mongering, changing financing will not change the audience.

Would the party that best represents the values of the people win? This is less likely if EVERYONE gets equal air time. People will vote to their nieche and the one nieche will win. This problem could be ameliorated with a run off election system, and I think that is only possible with a constitutional amendment.

Consequently, people with power that can't be transmuted into money would likely have more influence in an election where everyone has the same amount within their coffers. This can be mitigated by making politicians reliant on money. It can help democratize the process because groups of people can get together and raise money to counter the influence of the few powerful individuals. It isn't perfect, but you're making a trade off between different types of power.

I also think that after a certain amount of cash is spent, the marginal value of each additional dollar spent to buy a politician buys less influence than the prior dollar. Meaning, after you spent $1 billion on an ad buy you are less likely to change additional opinions with the next $1 billion and you are likely not going to change anything at all with another $1 million on top.

My guess is that any longer term solution for meaningful change is to get "we the people" more engaged in the political process. The logarithmic return on campaign dollars leaves room for people to vote based upon their cultural programming. So, (1) educate people to believe in what you believe and also (2) how to think critically, they will be less susceptible to campaign ads.