This November, a wave of student activism drew attention to the problem of racism at colleges and universities in the US. Sparked by protests at the University of Missouri, nicknamed Mizzou, we saw actions at dozens of colleges. It was a spectacular show of strength and solidarity and activists have won many concessions, including new funding, resignations, and promises to rename buildings.

Activists’ grievances are structural — aimed at how colleges are organized and who is in charge, what colleges teach and who does the teaching, and what values are centered and where they come from — but they are also interpersonal. Student activists of color talked about being subject to overtly racist behavior from others and being on the receiving end of microaggressions, seemingly innocuous commentary from others that remind them that they do not, as a Claremont McKenna dean so poorly put it, “fit the mold.” That dean lost her job after that comment. Many student activists seem to embrace the policing of offensive speech, both the hateful and the ignorant kind.

Negative reactions to this activism was immediate and widespread. Much of it served only to affirm the students’ claims: that we are still a racist society and that we, at best, tolerate our young people of color only if they stay “in their place.” Other times, it was confusion about the kind of world these young people seemed to want to live in. Why, some people asked, would anyone — especially a member of a marginalized population — want to shut down free speech?

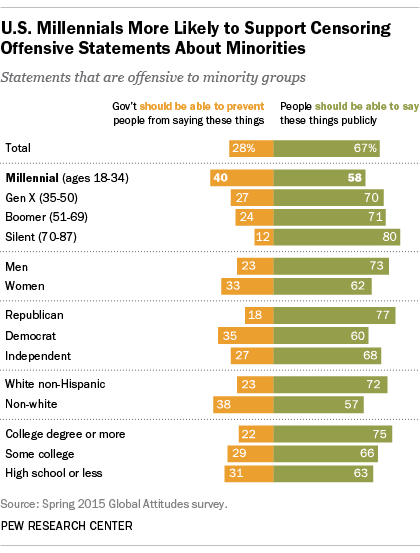

Well, it may be that the American love of free speech is waning. The Pew Research Center released data measuring attitudes about censorship. They asked Americans whether they thought the government should be able to prevent people from saying things that are “offensive to minorities.” Millennials — that is, today’s college students — are significantly more likely than any other generation to say that they should.

In fact, the data show a steady decrease in the proportion of Americans who are eager to defend speech that is offensive to minorities. Only 12% of the Silent generation is in favor of censorship, compared to 24% of the Baby Boomers, 27% of Gen X, and 40% of Millennials. Notably, women, Democrats, and non-whites are all more likely than their counterparts to be willing to tolerate government control of speech.

Americans still stand out among their national peers. Among European Union countries, 49% of citizens are in favor of censorship, compared to 28% of Americans. If the Millennials have anything to say about it, though, that might be changing. Assuming this is a cohort effect and not an age effect (that is, assuming they won’t change their minds as they age), and with the demographic changes this country will see in the next few decades, we may very soon look more like Europe on this issue than we do now.

Re-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 8

Grace Oxley — December 3, 2015

This article artfully conflates hate speech and slander with "free speech" and legal consequences for inflammatory or offensive speech with censorship. Try defining how they wish to implement the prevention before calling it censorship. The conclusions are misleading since they aren't accurate extrapolations of the assessment.

Amadi — December 3, 2015

Students cannot "shut down free speech" even using the phrase colloquially. Facing consequences when your speech is false or creates harm to others isn't having your free speech shut down, its being held accountable. The framing of this post is garbage.

kafkette — December 3, 2015

have we reappraised, revaluated, and recodified last mid-century's dystopian novels yet? our syntagms are slipping. perhaps they're just becoming orgasmic syntagms, since we really have little interest in much else. regardless, there must be at least a few theses flitting about that do not merely assert but, instead, proudly proclaim that there's nothing wrong with chopping and changing literature, at the very least [particularly since anything that isn't contemporary is unnecessary]—anyway there must be several theses proffering proof that the world of 1984 isn't so bad, really—at least with a few of our prefered alterations. yes?

because if there isn't yet, there will be soon. the most frightening thing of all? the lack of outrage that this day is not just on its way, it's already here. no. wait. the most frightening thing of all? that people have become too stupid to understand how horrifying is the dream we now all seem to be compelled to activate. and the best thing? that the last bright spots remaining of our reckless wretched world will have died by the time the joy of emotionless fukcing combined with relentless verbal repression hits the everlovin fan —and explodes.