Flashback Friday.

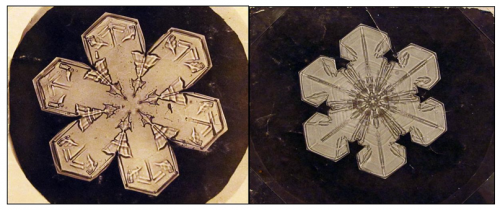

The image above is a photograph of a snowflake taken in the late 1800s by Wilson Bentley. Bentley, a 19-year-old farmer in Vermont, was the first person to ever photograph snowflakes. From the Guardian:

Bentley’s obsession with snow crystals began when he received a microscope for his 15th birthday. He became spellbound by their beauty, complexity and endless variety.

“Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty; and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind,” he said.

Bentley started trying to draw the flakes but the snow melted before he could finish. His parents eventually bought him a camera and he spent two years trying to capture images of the tiny, fleeting crystals.

He caught falling snowflakes by standing in the doorway with a wooden tray as snowstorms passed over. The tray was painted black so he could see the crystals and transfer them delicately onto a glass slide.

To study the snow crystals, Bentley rigged his bellows camera up to the microscope but found he could not reach the controls to bring them into focus. He overcame the problem through the imaginative use of wheels and cord.

Bentley took his first successful photomicrograph of a snow crystal at the age of 19 and went on to capture more than 5,000 more images.

What struck me about this story, other than the pretty pictures and neat historical trivia, was the fact that nearly every schoolchild in the Western world knows what a snowflake looks like under a microscope, even as their experience of snowflakes is mostly of them as cold, fuzzy, frozen blobs, if they have any regular experience with snow at all. They know because we teach them.

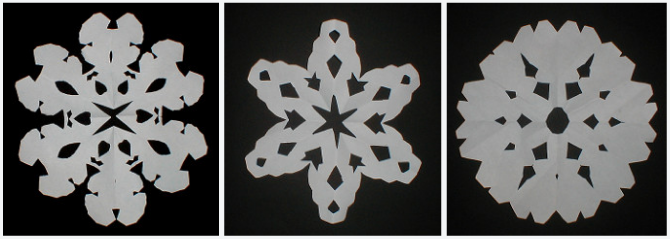

The idea of the meme is one way to discuss our ability to transfer elusive knowledge like this. A meme is a unit of knowledge or a type of behavior that’s passed on from generation to generation culturally. The gene is its evolutionary cousin, passing along knowledge and behavior genetically. In the US, this particular knowledge meme is found in books or scientific discussions, but it has also become a common arts and craft project: many of us learn about snowflakes when we are shown how to make them from construction paper:

It’s quite amazing to consider how every human generation since Bentley understands the snowflake just a little bit differently than anyone before him. Because of the advantage that human culture gives each new generation, nearly every child learns to appreciates their beauty.

See a slide show of his photographs at The Telegraph. This post originally appeared in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 28

K — April 19, 2010

It's problematic to accept "knowledge" that doesn't come from direct experience. But on the other hand, there's definitely a practical limit to just how much we can experience. I trust that the US had a Civil War (or "war among the states," or whatever sort of biased name the war could have), and that dogs have hearts, and that airplanes manage to stay in the air because of lift.

I'm starting to sound like that horrible "Miracles" song by Insane Clown Posse.

Ollie — April 19, 2010

I liked this article. For some reason it feels like the folk song of sociological images.

Tai — April 19, 2010

Under the right conditions, you can see snowflake crystals with the naked eye. I know what a snowflake looks like because I've seen them. If it's relatively warm out, yes, they just look like blobs, but if it's cold enough, they retain their structure when they fall onto your mittens.

contrabalance — April 19, 2010

"Are memes a scientific discovery? Well, one thing is absolutely certain; if they are, they are the most effortless scientific discovery of all time. For what did it take, after all? What was the evidence and the reasoning, that enabled Dawkins to discover memes in 1976, although their very existence, like that of genes before 1900, had been unsuspected before?

Well, to tell the truth, it was nothing more than the following.

Sometimes such things as beliefs, attitudes etc., are transmitted non-genetically from one person to another.

So

There are memes.

I can only echo Huxley's famous remark after he first read The Origin of Species: 'How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!'... there is something very familiar about Dawkins' discovery, at any rare to a philosopher: something horribly familiar, in fact. I have seen that kind of thing hundreds of times before, but where? Why, in those absolutely effortless pseudo discoveries which philosophers make, and on which their fame rests...”

-- David C. Stove - "Darwinian Fairytales" pg. 130

MPS — April 19, 2010

I want to make you aware of the superior pictures here:

http://www.its.caltech.edu/~atomic/snowcrystals/

Emma Apple — April 19, 2010

My kids are fortunate enough to have seen the shape of snowflakes first hand. I however come from a place where it doesn't snow and didn't experience snow until I was 19. I didn't know people could actually see them with the naked eye until I saw them myself.

Lindsay — April 19, 2010

I didn't experience fresh snow until I was 18. As I was walking through my first heavy snowfall I thought that it felt like I was in a movie... the sociological significance of that did not escape me.

When I caught snow on my black gloves, I probably said 'whoa' aloud, because somehow I didn't believe that they really looked like that. The photographer in me also immediately popped up with ideas.

Despite the dark glove argument, I doubt we would see the structure of a snowflake as much more than an asterisk without microscopes.

Ike — April 20, 2010

I never saw snow until I was 10, but well before then, I was cutting paper to look like "snowflakes". Go meme!

Hans Bakker — April 20, 2010

I completely agree that using Dawkins' word "meme" as anything more than a kind of poetic trope is highly misleading. We might as well say "phlogisten." There is no scientific definition or "operational definition" of a meme. It is fine for journalistic usage, but we might as well give up on natural science, physical science and social science if we cannot differentiate among common sense usage, journalistic hype and truly scientific technical terms. If we wish to discuss the ways in which "ideas" are transmitted then that would be less confusing. The concept of a "gene" in molecular biology and genetics has real scientific value. The term "meme" is only a very rough analogy. There is no "memome" that can be mapped by reductionist science. What we do have is "cultures" and "structures" in societies. On the other hand, if we do want to think very, very broadly and start to designate the word "meme" as a scientific concept, then Dawkins' views on religion would have to be re-thought "scientifically" as well. What is more "meme-like" than theological notions like "angels."

Hans Bakker — April 20, 2010

I do like the general idea that we often think we know something because we have been told it is so, even though we never actually did inductive observations of any kind. Without looking, ask yourself which way Abraham Lincoln in facing on the American penny? Without looking, ask yourself who is on the Canadian penny? Which way is that person looking? Are they both looking in the same direction? What are the words on the face side of each penny? What are the words on the tails side of each penny? We touch and feel and see pennies every day, but we do not "observe" them at all.

jane kellar — April 20, 2010

hi , my daughter just sent me The Snowflake and the Meme. There is a wonderful book, "Snow Crystals" published by Dover Press. My copy is from the early 70's, but it may still be available.It contains 2,453 of Bentley's photographic plates. He started photographing snowflakes when he was 19- in 1885! Quite amazing!!! they later published an abridged version, with 72 plates of Bentley's, in 2000. There is a childrens' book, "Snowflake Bentley" by Jacqueline B. Martin, illustrated by that wonderful Vermont illustrator, Mary Azarian. I grew up on a farm where we spent endless hours out in the snow. I remember looking into the snow as it fell. Hypnotizing. Catching flakes on our tongues, our clothing, and being mesmerized by the incredibleness of these tiny, intricate flakes. By the way, the Inuit have many(400+/-) names for the various types of snow: soft, thin ice on snow, snow on ground, on water, sparkling in sunlight, moonlight, starlight.,shaken off in mud room, clinging, drifted.... thanks for the comments. jane

Julia Wise — April 20, 2010

In some cases, when we can see the actual shapes of things we have some kind of archetypical shape taught to us by our culture. Real hearts look like muscular globs, not heart shapes. Real stars look like dots, not five-pointed star shapes. But kids can draw the star shape and the heart shape.

My husband and I were wondering recently if the same heart shape exists in other cultures. Does anyone know?

Blix — August 16, 2011

A lot of today's Christmas cards would have freaked people out. "What is that?!?" "I don't know...maybe a secret enemy symbol."

Shop Local, Play Global | QuinnCreative — November 25, 2011

[...] Sit down with your kids or grandkids and teach them how to make a snowflake using this diagram from http://thesocietypages.org [...]

DECEMBER 5. | Szivárványzene — December 5, 2013

[…] 5 Egy szép sablont és egy videot is mellékelek Nektek hasznosításra! Megjegyzés: ez egy […]

Milf Sex in NZ — April 8, 2025

Experiencing time with Milf Sex in NZ always makes lasting feelings.

Private Nutten — May 5, 2025

Dialogführen mit Geile Hobbynutten wunderschön ist eine Entdeckung wertvoll, die meine Stimmung hebt.