I’m on a plane right now, flying from Sacramento back to Albany. And sitting here I’m reminded of how air travel itself reflects the growing inequality of society in a trivial, but suggestive, way.

Planes have always had first-class and passenger cabins, at least as far as I know. If the Titanic had this distinction, I’m guessing it was in place from the beginning of commercial aviation.

But for most of my adult life, planes — at least the ones I usually fly on, from one U.S. city to another — looked something like this:

Just roughing it out here, this means that 7% of the passengers used about 15% of the room, with the other 93% using 85% of the cabin space. Such a plane would have a Gini index of about 8. The Gini index is measure of inequality, a fancy statistical way of representing inequality in the income distribution of a country’s population. For reference, the U.S. Gini is about 48, and the global one is around 65.

Domestic airlines have pretty much moved to a three-tier system now, in which the traditional first-class seating is supplemented by “Economy Plus,” in which you get an extra three or four inches of legroom over the standard “Economy” seats. I, as usual, am crammed into what should really be called “Sardine Class” — where seats now commonly provide a pitch of 31”, a few inches down from what most planes had a decade ago.

In today’s standard U.S. domestic configuration, the 12% of people in first class use about 25% of the passenger space, the 51 people in Economy Plus use another 30%, leaving the sardines — the other 157 people — with 45%. That gives us a Gini index of about 16.

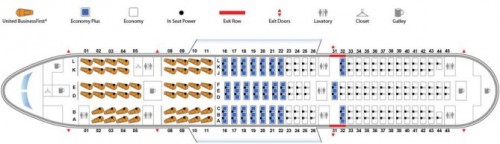

Transatlantic flights, however, are increasingly taking this in-the-air distinction to new heights. Take, for example, the below United configuration of the Boeing 777. It boasts seats that turn into beds on which one can lie fully horizontal. United calls this new section of bed-seats “BusinessFirst.”

Unsurprisingly, though, these air-beds take up even more space than a nice comfy first class seat. So if we look again at how the space is distributed, we now have 19% of the people using about 35% of the plane, 27% using another 25%, and the final 52% using the last 40%. The Gini index has now increased to 25.

It’s not often you see such a clear visual representation of our collective acceptance of the right of a small fraction of people to consume a very disproportionate percentage of resources. I wonder how much of the shift is actually driven by increased inequality, as opposed to improved capacity for price discrimination.

And it’s also worth noting that the plane above, while unequal relative to the old-fashioned three-rows-of-first-class-and-the-rest-economy layout, is still nowhere near the inequality of the U.S., or the world.

Elizabeth Popp Berman, PhD is an associate professor of sociology at the University at Albany. She is the author of Creating the Market University: How Academic Science Became an Economic Engine and regularly blogs at OrgTheory, where this post originally appeared.

Comments 16

Fuzzy — December 15, 2014

Ummm. It might be pointed out that the people using that space pay handsomely for it....

Álvaro — December 15, 2014

First world problems...

Bill R — December 15, 2014

The correlation between relative net worth of air travelers and seating space is certainly positive but probably not as high as you'd think. First class is littered with frequent flyers whose richer bosses are back home with their families and those who suffer from conspicuous consumption.

But, bottom line, Alvaro has the issue nailed pretty good.

gasstationwithoutpumps — December 15, 2014

The reason the Gini index for planes is not so huge is that it does not include private jets (for the very rich) and the enormous numbers of people who can't afford to fly at all.

Larry Charles Wilson — December 15, 2014

I just might start flying again.

A frequent flyer — December 15, 2014

Of course, unlike the Titanic, a plane crash is an equal opportunity event.

kafkette — December 15, 2014

& actual poor people go by dog*.

but we dont know any actual poor people here, sometimes i forget.

*greyhound, because those of us who have neither been nor known any aspects of impoverishment also dont know the lingo, the jargon, the lingua franca, whatever.

we do complain, though, about being forced to travel aboard airlines. terrible stuff, that, especially when one is impelled, just forced, to do it so frequently.

Fundstücke/Trouvailles: Economists in Search of Historization and of Scientific Debate, Airplane Inequality, | Moral Economy — December 16, 2014

[…] Inequality in the Skies: Applying the Gini Index to Airplanes - Elizabeth Popp Berman in: Sociological Images – originally on: Orgtheory.net […]

Elena — December 16, 2014

Planes have always had first-class and passenger cabins, at least as far

as I know. If the Titanic had this distinction, I’m guessing it was in

place from the beginning of commercial aviation.

Think trains. See the engravings here, third class wagons in the 1830s-40s were open to the elements.

Heather — December 16, 2014

Before deregulation, airfares were much higher and airlines made profit on every seat. Now the airlines only really make profit on the business class+ fares, so of course they allot more of their plane to those seats. Those higher fares also allow for economy tickets to be as low as they are. A round trip DC-San Francisco economy ticket usually runs me between $250-$500. I just checked--that's less than taking a bus round trip. And I get there in ~5 hours.

These premium seats may have a bigger proportion of the plane than in years pasts, but they are enabling incredibly low fares.

Maximilian Hohenzollern — August 3, 2023

I haven't had a vacation for a long time, so this time I'm looking forward to getting back on the plane and flying on my trip. By the way, I like to plan my trips in advance, so I decided to find as many vacation options as possible. For example, food tours Lisbon seemed like an extremely interesting idea to get to know the culture and local traditions through food