I don’t yet have a copy of Matt Richtel’s new book, A Deadly Wandering: A Tale of Tragedy and Redemption in the Age of Attention. Based on his Pulitzer-prize winning reporting for the New York Times, however, I’m afraid it’s unlikely to do justice to the complexity of the relationship between mobile phones and motor vehicle accidents. Worse, I fear it distracts attention from the most important cause of traffic fatalities: driving.

A bad sign

The other day Richtel tweeted a link to this old news article that claims texting causes more fatal accidents for teens than alcohol. The article says some researcher estimates “more than 3,000 annual teen deaths from texting,” but there is no reference to a study or any source for the data used to make the estimate. As I previously noted, that’s not plausible.

In fact, only 2,823 teens teens died in motor vehicle accidents in 2012 (only 2,228 of whom were vehicle occupants). So, I get 7.7 teens per day dying in motor vehicle accidents, regardless of the cause. I’m no Pulitzer-prize winning New York Times journalist, but I reckon that makes this giant factoid on Richtel’s website wrong, which doesn’t bode well for the book:

In fact, I suspect the 11-per-day meme comes from Mother Jones (or someone they got it from) doing the math wrong on that Newsdaynumber of 3,000 per year and calling it “nearly a dozen” (3,000 is 8.2 per day). And if you Google around looking for this 11-per day statistic, you find sites like textinganddrivingsafety.com, which, like Richtel does in his website video, attributes the statistic to the “Institute for Highway Safety.” I think they mean the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, which is the source I used for the 2,823 number above. (The fact that he gets the name wrong suggests he got the statistic second-hand.) IIHS has an extensive page of facts on distracted driving, which doesn’t have any fact like this (they actually express skepticism about inflated claims of cellphone effects).

After I contacted him to complain about that 11-teens-per-day statistic, Richtel pointed out that the page I linked to is run by his publisher, not him, and that he had asked them to “deal with that stat.” I now see that the page includes a footnote that says, “Statistic taken from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety’s Fatality Facts.” I don’t think that’s true, however, since the “Fatality Facts” page for teenagers still shows 2,228 teens (passengers and drivers) killed in 2012. Richtel added in his email to me:

As I’ve written in previous writings, the cell phone industry also takes your position that fatality rates have fallen. It’s a fair question. Many safety advocates point to air bags, anti-lock brakes and wider roads — billions spent on safety — driving down accident rates (although accidents per miles driven is more complex). These advocates say that accidents would’ve fallen far faster without mobile phones and texting. And they point out that rates have fallen far faster in other countries (deaths per 100,000 drivers) that have tougher laws. In fact, the U.S. rates, they say, have fallen less far than most other countries. Thank you for your thoughtful commentary on this. I think it’s a worthy issue for conversation.

I appreciate his response. Now I’ll read the book before complaining about him any more.

The shocking truth

I generally oppose scare-mongering manipulations of data that take advantage of common ignorance. The people selling mobile-phone panic don’t dwell on the fact that the roads are getting safer and safer, and just let you go on assuming they’re getting more and more dangerous. I reviewed all that here, showing the increase in mobile phone subscriptions relative to the decline in traffic accidents, injuries, and deaths.

That doesn’t mean texting and driving isn’t dangerous. I’m sure it is. Cell phone bans may be a good idea, although the evidence that they save lives is mixed. But the overall situation is surely more complicated than TEXTING-WHILE-DRIVING EPIDEMIC suggests. The whole story doesn’t seem right — how can phones be so dangerous, and growing more and more pervasive, while accidents and injuries fall? At the very least, a powerful part of the explanation is being left out. (I wonder if phones displace other distractions, like eating and putting on makeup; or if some people drive more cautiously while they’re using their phones, to compensate for their distraction; or if distracted phone users were simply the worst drivers already.)

Beyond the general complaint about misleading people and abusing our ignorance, however, the texting scare distracts us (I know, it’s ironic) from the giant problem staring us in the face: our addiction to private vehicles itself costs thousands of lives a year (not including the environmental effects).

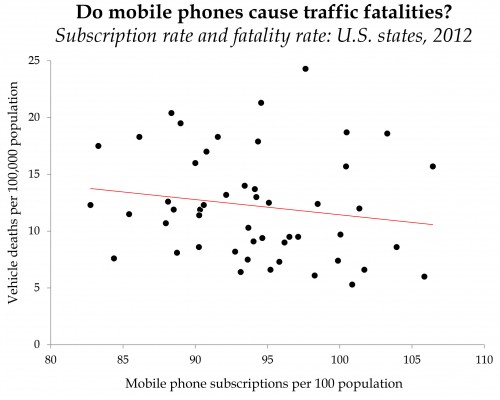

To illustrate this, I went through all the trouble of getting data on mobile phone subscriptions by state, to compare with state traffic fatality rates, only to find this: nothing:

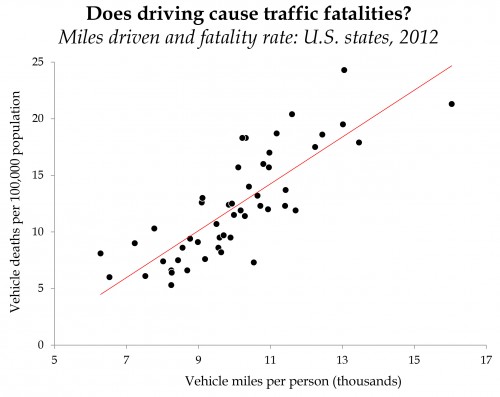

What does predict deaths? Driving. This isn’t a joke. Sometimes the obvious answer is obvious because it’s the answer:

If you’re interested, I also put both of these variables in a regression, along with age and sex composition of the states, and the percentage of employed people who drive to work. Only the miles and drive-to-work rates were correlated with vehicle deaths. Mobile phone subscriptions had no effect at all.

Also, pickups?

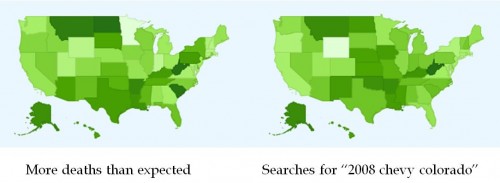

Failing to find a demographic predictor that accounts for any of the variation after that explained by miles driven, I tried one more thing. I calculated each state’s deviation from the line predicted by miles driven (for example Alaska, where they only drive 6.3 thousand miles per person, is predicted to have 4.5 deaths per 100,000 but they actually have 8.1, putting that state 3.6 points above the line). Taking those numbers and pouring them into the Google correlate tool, I asked what people in those states with higher-than-expected death rates are searching for. And the leading answer is large, American pickup trucks. Among the 100 searches most correlated with this variable, 10 were about Chevy, Dodge, or Ford pickup trucks, like “2008 chevy colorado” (r = .68), shown here:

I could think of several reasons why places where people are into pickup trucks have more than their predicted share of fatal accidents.

So, to sum up: texting while driving is dangerous and getting more common as driving is getting safer, but driving still kills thousands of Americans every year, making it the umbrella social problem under which texting may be one contributing factor.

I used this analogy before, and the parallel isn’t perfect, but the texting panic reminds me of the 1970s “Crying Indian” ad I used to see when I was watching Saturday morning cartoons. The ad famously pivoted from industrial pollution to littering in the climactic final seconds:

Conclusion: Keep your eye on the ball.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Comments 17

Bill R — October 8, 2014

That traffic fatalities vary by total miles driven is intuitive and well understood.

But your graph showing no correlation between vehicle deaths and cellphone subscriptions misses the mark.

The question of interest is: What percentage of fatal accidents occurred either during or immediately before/after an occurrence of cell phone use in the car?

Plotting the number of vehicle deaths by the number of subscriptions does not directly address this question.

Bern — October 11, 2014

The mobile-phone subscriptions metric that forms the premise of your discussion here is specious. As the other commenter points out, subscription rates have no relationship to the frequency of texting and driving. You need data that demonstrates the percentage of accidents caused by mobile phones. This surely exists (and, given that some states banned texting before others, comparative data would be available). Either you're really lazy, or the existing data contradicts your premise that there's a weak correlation between texting and accidents. Does the fact that you spend half this article discussing one incorrect statistic found on a publisher's website suggest something to you? You've proved that driving cars causes car accidents (slow clap). You have not proved that texting campaigns or bans are hysteric.

Society Pages and Pacific Standard should consider taking this article down.

ThatGuy82 — October 13, 2014

I tend to a agree with bill on this, the correlation seems to have a hidden confound in that how do we know if those that own and operate a cell phone are also likely to own and operate a motor vehicle?

There's no way to tell with this data and makes the conclusion jump the gun.

Mike C — October 13, 2014

It's not drinking either.... it's drinking and driving just as "text and drive"

Lucas — October 13, 2014

When someone claims that he or she "generally opposes scare-mongering manipulations of data that take advantage of common ignorance", an observer expects a sound data analysis to substantiate that person's arguments.

First of all, how is vehicle deaths correlated with mobile phone subscriptions a test of mobile phone being dangerous when driving? It is not vehicle deaths while texting/phoning someone. It also does not contain actual usage while driving. Secondly, of course miles driven correlate with the number of accidents, so does the number of cars sold, volume of car fuel sold in gas stations, etc. But the only thing that it means, is that you should control for it in a proper regression model, because it is simply increased opportunities. Just like you control for population size differences by using average deaths normalized per 100,000 people - that's because, surprise surprise, population size is correlated with the number of deaths!

Finally, in a regression model the effect sizes are not correlation coefficients.

[/rant]

Peter W — October 13, 2014

more naive empiricism

mograph — October 13, 2014

Hmm ... traffic fatalities correlated with mobile phone subscriptions to study the relationship between texting and driving?

Do we have a failure of construct validity here?

The cause of traffic fatalities is driving - Lawyers, Guns & Money : Lawyers, Guns & Money — October 14, 2014

[…] post by Philip Cohen on the absurd misdirection and dubious statistics surrounding the texting-while-driving panic. The […]

Phillip — October 15, 2014

That analogy reminds me of Louis C.K.'s comments on how littering within a city is kinda redundant haha

http://youtu.be/GTH8htzsrX4

pdquick — October 15, 2014

The "Crying Indian" was an Italian guy from New York.

Killer Cars | The Penn Ave Post — October 16, 2014

[…] at 8:15 on October 16, 2014 by Andrew Sullivan Philip Cohen contends that campaigns against texting while driving “distract us (I know, it’s ironic) from the […]

eric72 — October 16, 2014

"To illustrate this, I went through all the trouble of getting data on mobile phone subscriptions by state, to compare with state traffic fatality rates, only to find this: nothing."

Duh.

markipooh — October 16, 2014

What a terrible analysis. First, owning a cell phone is not the same as texting - so state level cell phone ownership rates are pretty meaningless. Second, accidents occur at the individual level - aggregating statistics to the state level can obscur the real relationship between texting (not even measured here) and accident rates (or accident risk).

There are lovely (i.e., scary) data on the real relationship between texting and accidents from analyses using actual texting behavior and actual crashes and near-crashes. Here is the link to just one recent study from the New England Journal of Medicine.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1204142

Please note that that doing pretty much anything on a cell phone while driving massively inflates your risk of getting into an accident.

Please stop spreading this kind of nonsense

Everyday Sociology on the Road – Activity Posting 4 | cookbook — October 20, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2014/10/08/the-no-1-cause-of-traffic-fatalities-its-not-texting… […]