In Generation Me and The Narcissism Epidemic, psychologist Jean Twenge argues that we’re all becoming more individualistic. One measure of this is our willingness to go against the crowd. She offers many types of evidence, but I was particularly intrigued by her discussion of the afterlife of a famous experiment in psychology.

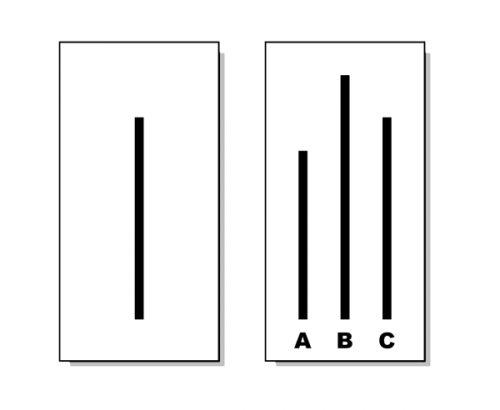

In 1951, social psychologist Solomon Asch placed eight male Swarthmore students around a table for an experiment in conformity. They were asked to consider two cards, one with three lines of differing lengths and another with one line. He asked each student, one by one, which line on the card of three was the same length as the lone line on the second card. Each group looked at 18 pairs of cards like this:

Asch was only interested in the last student’s response. The first seven were confederates. In six trials, Asch instructed all the confederates to give the correct answer. In twelve, however, the other seven would all choose the same obviously wrong answer. Asch counted how often the eighth student would go against the crowd in these cases, breaking consensus and offering up a solitary, but correct answer.

He found that conformity was surprisingly common. Three-quarters of the study subjects incorrectly went with the majority in at least one trial and a third did so half the time or more. This was considered a stunning example of people’s willingness to lie about what they are seeing with their own eyes in order to avoid rocking the boat.

But then there was Vietnam and anti-war protesters, hippies and free love, the women’s and gay liberation movement, and civil rights victories. By the 1960s, it was all about rejecting the establishment, saying no, and envisioning a more authentic life. Things changed. And so did this experiment.

By the mid-1990s, there were 133 replications of Asch’s study. Psychologists Rod Bond and Peter Smith decided to add them all up. They found that the tendency for individuals to conform to the group fell over time.

One of the abstract take-away points from this is that our psychologies — indeed, even our personalities — are malleable. In fact, the results of many studies, Twenge writes, suggest that “when you were born has more influence on your personality than the family who raised you.” When encountering claims of timeless and cultureless truths about human psychology, then, it is always good to ask ourselves what scientists might find a few decades later.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 8

Larry Charles Wilson — June 23, 2014

I'm always amazed at the rediscovery of the wheel.

Question — June 23, 2014

There were protests and changes, yes .... But there were also thousands of students being taught about this kind of experiment in psychology class! How come that never seems to be mentioned or taken into account? Learning about these experiments affects how you react to those situations in the future. Learning about the bystander effect definitely helped spur me to be the one to call 911 when it was needed and there was a crowd standing around. If I were in a study to measure conformity I'd probably realize it.

Question — June 23, 2014

Maybe just growing awareness that these experiments are always trying to trick you somehow, even if they don't know this particular one.

Bill R — June 23, 2014

There's no pseudo-science like old pseudo-science.

Post WWII social psychologists and related academics tried to explain how ordinary citizens could turn into murdering Nazis. See Zimbardo's and Milgram's breathtaking work of example.

Some lesser researchers got caught up in the logical fallacy involved in creating imaginary constructs. That's what's happening in this post.

The researcher starts off with the construct, here wanting to prove that people are essentially conformists, then they build an experiment to make their case and argue rhetorically that they've discovered what they set out to.

But they don't consider logical alternatives that could defeat their underlying assumptions or leave them open to doubt. For example, I may set out to prove that people are essentially gullible or lack confidence in their own judgement even in the face of simple stimuli and use the same experiment to make my case.

Conformity is just the researchers rhetoric in this study. It does't have a firm basis in reality.

Mathew Toll — June 23, 2014

Great post. The meta-study is 18 years old though, I wonder what's happened since then.

Quin Callahan — June 24, 2014

Why does the first half of this article explain in detail the data found, but the second only has a link to the study?

Corrosion of Conformity | — June 29, 2014

[…] This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standardpartner site, as “Is America’s Personality Changing? A Decline in the Willingness to Conform.” […]

Beth Day — July 19, 2014

Do you think the change is linear, or non-linear?