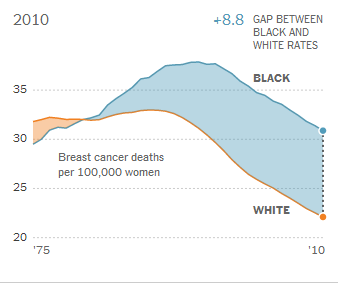

Thanks to advances in early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, white women’s survival rates have “sharply improved,” but black women’s have not. As a result, white women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer, but black women are more likely to die from it. Researchers from the Sinai Institute found that Black women are 40% more likely to die from the disease than white women.

Experts trace the majority of the widening gap in survival rates to access, not biology. Black women are more likely than white to be low income, uninsured, and suspicious of a historically discriminatory medical profession.

From Tara Parker-Pope for the New York Times. Hat tip @ProfessorTD.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 12

Geoff Smith — February 1, 2014

Maybe widening means something different to some people, but it looks like it's been within .1-.2 of a 9 point difference for almost 15 years, and if you look at NY, NJ, CT, and MA things look close to parity, which is kind of impressive. It seems like a solved problem if the rest of the states would adopt the policies of those 4.

I'm actually more interested in the wide swings, and the fact that at the beginning of these timeframes black women appeared to do better. Is it because they were dying of something else (childbirth, perhaps?) or has something happened to increase the rate of breast cancer in general? Why did black women's rate of death increase in the 80s and 90s? I could understand if they were suffering from discrimination that resulted in delay of incorporation of the new treatments, but how in the world would that have resulted in such a drastic INCREASE in morality if the only difference if white women have better access to technology than black women did in this period? Technology that didn't even exist when black women did better in this arena.

This story is missing too much, and even the NYT is really lacking in detail. Black women now die more often of breast cancer than they did in 1975, and I find it hard to imagine that discrimination is worse now than it was then. There has to be something else going on here, but what is it?!? This doesn't make any sense to me, there's something else going on here. The idea that black women are doing worse than they used to because they don't have access to advances that didn't exist at the beginning of the study seems ludicrous to me..

Bagelsan — February 1, 2014

Obviously we need some fucking single-payer!

jon — February 2, 2014

Very interesting... Did they control for income level and obesity in their analysis /regressions? HRS would have this data or national health interview survey, I suspect.

Also a fixed effects model, if they had longitudinal data, could control for unobserved constant individual factors like childhood experiences or perception of racism (which could lower health over life course).

Its actually not that hard to tease out these factors, statistically speaking, with the right data and models. But research in medical journals, unfotunately, still tends to be very crude in terms of regression modelling.. They are great on some things, but regressions are sometimes not one of them

Agrajag — February 4, 2014

It'd be interesting to track what is the case: Is it that black women are more likely to GET breast-cancer, or is it that black women are more likely to DIE FROM breast cancer, or is it a little of both ?

Some risk-factors of breast-cancer are linked to poverty, so part of the gap could in principle be explainable as: black women are more likely to be poor than white women are.

Yrro Simyarin — February 4, 2014

Is the racial divide a useful one here, or is it just obscuring the correlation for income?

素晴らしいインフォグラフィクスは常にシンプルだが、決してシンプル過ぎない。 | InfoGraphToday — April 1, 2014

[…] thanks to Sociological Images, I discovered this interactive example made in December 2013 by NYTimes’ Hannah […]