Many critics are praising 12 Years a Slave for its uncompromising honesty about slavery. It offers not one breath of romanticism about the ante-bellum South. No Southern gentlemen getting all noble about honor and no Southern belles and their mammies affectionately reminiscing or any of that other Gone With the Wind crap, just an inhuman system. 12 Years depicts the sadism not only as personal (though the film does have its individual sadists) but as inherent in the system – essential, inescapable, and constant.

Now, Noah Berlatsky at The Atlantic points out something else about 12 Years as a movie, something most critics missed – its refusal to follow the usual feel-good cliche plot convention of American film:

If we were working with the logic of Glory or Django, Northup would have to regain his manhood by standing up to his attackers and besting them in combat.

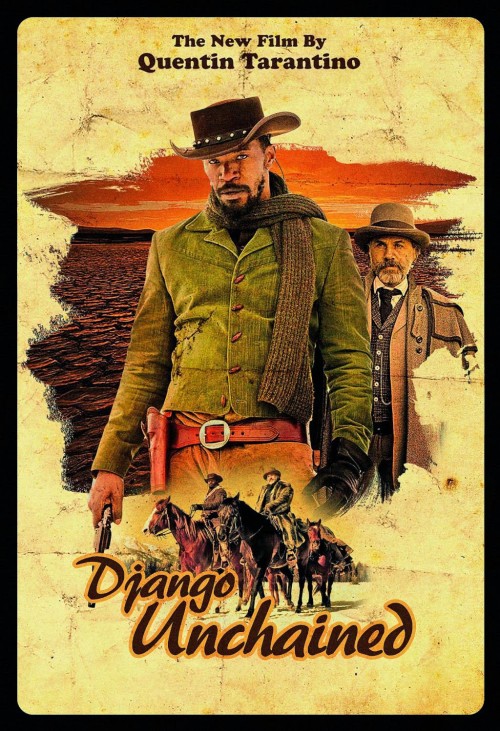

Django Unchained is a revenge fantasy. In the typical version, our peaceful hero is just minding his own business when the bad guy or guys deliberately commit some terrible insult or offense, which then justifies the hero unleashing violence – often at cataclysmic levels – upon the baddies. One glance at the poster for Django, and you can pretty much guess most of the story.

It’s the comic-book adolescent fantasy – the nebbish that the other kids insult when they’re not just ignoring him but who then ducks into a phone booth or says his magic word and transforms himself into the avenging superhero to put the bad guys in their place.

This scenario sometimes seems to be the basis of U.S. foreign policy. An insult or slight, real or imaginary, becomes the justification for “retaliation” in the form of destroying a government or an entire country along with tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of its people. It seems pretty easy to sell that idea to us Americans – maybe because the revenge-fantasy scenario is woven deeply into American culture – and it’s only in retrospect that we wonder how Iraq or Vietnam ever happened.

Django Unchained and the rest are a special example of a more general story line much cherished in American movies: the notion that all problems – psychological, interpersonal, political, moral – can be resolved by a final competition, whether it’s a quick-draw shootout or a dance contest. (I’ve sung this song before in this blog, most recently here after I saw Silver Linings Playbook.)

Berlatsky’s piece on 12 Years points out something else I hadn’t noticed but that the Charles Atlas ad makes obvious: it’s all about masculinity. Revenge is a dish served almost exclusively at the Y-chromosome table. The women in the story play a peripheral role as observers of the main event – an audience the hero is aware of – or as prizes to be won or, infrequently, as the hero’s chief source of encouragement, though that role usually goes to a male buddy or coach.

But when a story jettisons the manly revenge theme, women can enter more freely and fully.

12 Years a Slave though, doesn’t present masculinity as a solution to slavery, and as a result it’s able to think about and care about women as people rather than as accessories or MacGuffins.

Scrapping the revenge theme can also broaden the story’s perspective from the personal to the political (i.e., the sociological):

12 Years a Slave doesn’t see slavery as a trial that men must overcome on their way to being men, but as a systemic evil that leaves those in its grasp with no good choices.

From that perspective, the solution lies not merely in avenging evil acts and people but in changing the system and the assumptions underlying it, a much lengthier and more difficult task. After all, revenge is just as much an aspect of that system as are the insults and injustices it is meant to punish. When men start talking about their manhood or their honor, there’s going to be blood, death, and destruction – sometimes a little, more likely lots of it.

One other difference between the revenge fantasy and political reality: in real life results of revenge are often short-lived. Killing off an evildoer or two doesn’t do much to end the evil. In the movies, we don’t have to worry about that. After the climactic revenge scene and peaceful coda, the credits roll, and the house lights come up. The End. In real life though, we rarely see a such clear endings, and we should know better than to believe a sign that declares “Mission Accomplished.”

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Comments 48

Fast Eddie — November 4, 2013

"This scenario sometimes seems to be the basis of U.S. foreign policy. An insult or slight, real or imaginary, becomes the justification for “retaliation” in the form of destroying a government or an entire country along with tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of its people."

Really? You mean you would consider the WTC attack an "insult or slight"? You would consider the possession of WMDs an "insult or slight"? In what cases has the USA toppled a government and killed hundreds of thousands of people because the USA was insulted?

I don't agree with the actions of the USA but saying the USA destroys nations and kills hundreds of thousands of people because it was "slighted" or "insulted" is a pretty dumb claim.

Yrro Simyarin — November 4, 2013

Seriously, who would have ever thought that you could end slavery by something as stupid and manly as winning a war.

anonymous — November 4, 2013

WMDs were never found

Elena — November 4, 2013

Berlatsky’s piece on 12 Years points out something else I hadn’t

noticed but that the Charles Atlas ad makes obvious: it’s all about

masculinity. Revenge is a dish served almost exclusively at the

Y-chromosome table. The women in the story play a peripheral role as

observers of the main event – an audience the hero is aware of – or as

prizes to be won or, infrequently, as the hero’s chief source of

encouragement, though that role usually goes to a male buddy or coach.

Given that Quentin Tarantino had just made *two* films about a woman's revenge (Kill Bill and Inglourious Basterds, which is Shoshanna's story more than the Basterds'), I can give him a pass for Django Unchained.

MJS — November 4, 2013

Django Unchained isn't a revenge story though. Django doesn't go to Candie's plantation intending to reap bloody vengeance. Rather, he's planning to use subterfuge in order to buy Broomhilda's freedom and he's perfectly willing to leave with her peacefully when Schultz (not Django) looses control and shoots Candie. This one act of revenge achieves nothing except to get Schultz killed and very nearly get both Django and Broomhilda killed as well and force Django to fight his way out of captivity and return to the plantation (more violently this time), not to get revenge against Stephen (though he does do that along the way) but to once again save Broomhilda.

Andrew — November 4, 2013

It is unfair to compare the two films; they have drastically different ambitions and nothing other than a historical setting in common. But if we are going to discuss "Django" in terms of its genre (which it deconstructed, flaunted, and subverted openly), it would be disingenuous not to admit that "Twelve Years a Slave" is also particularly Hollywood genre exercise - and arguably a less self-aware one at that.

Honestly, I think it's more a result of the tone than of the actual material that we tend to classify revenge-thrillers as lowbrow exploitation films while elevating redemption dramas and biographies to highbrow Art. Both storytelling conceits bait us with moral righteousness, galvanize us with the hardships of the hero's trials, and manipulate us toward the promise of catharsis with the triumph that ultimately redeems the hero's suffering and justifies our investment in his humanity. Both conventions bear no resemblance to reality, even if the source material is non-fiction.

The difference when it comes to these films is that Tarantino's work is made for an audience that is already pre-conditioned to examine the film through the lens of genre conventions. "Django" seamlessly grafted the Western - once the most traditionally white, conservative, and revisionist of genres, which largely erased the horror of American genocide - onto the Blaxploitation genre, in which revenge-fantasy was a thin veil for very real outrage at the very real awfulness of conditions in black urban America. By displacing well-known lowbrow narrative conventions into radical and uncomfortable contexts, and often discursively breaking form, Tarantino keeps the viewer intensely aware of how much content has always been embedded in the form of our narratives. The literal content of the stories - while very entertaining - is simply not the point of the movies.

A polemic drama live "Twelve Years a Slave" more closely resembles the prevailing convention of movies dealing with the horrors of history, persuading the audience to endure visceral accounts of suffering and rewarding it with moral resolution. We watch with the easy righteousness of hindsight, the comfortable reassurance of knowing that we remain firmly on the side of the good characters and can easily spot the bad ones; we can even sanctimoniously applaud ourselves for being appropriately disturbed by the graphic depictions of violence, so certain are we that the perpetrators have already been consigned to our personal Bad List.

When the lights go up, we return to a world in which we are all complicit in immeasurably awful contemporary evils, with no clear villains or heroes, and congratulate ourselves for consuming a Serious Highbrow Dramas instead of the lightweight entertainments that use exactly the same storytelling conventions.

MinTaec — November 5, 2013

There's a lot more going on with Django Unchained than a revenge fantasy - Django internalises the oppression, and ends up wearing Candie's coat and repeating his words. I think it's a lot more sophisticated in its exploration of narrative, socialisation and internalised racism than it's critics give it credit for because they're so quick to put Tarantino in the "ignorant film-maker" box.

quitus — November 5, 2013

FANTASY>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>REALITY

Ratoslov — November 5, 2013

As far as I can tell from your review, the only thing you've seen of 'Django Unchained' is it's poster.

#confuzzled — November 5, 2013

12 Years A Slave is a totally feel-good movie. We're supposed to feel bad about the system and feel bad for the protagonist, and presumably feel good feeling what we know is right to feel.

Having no fun while confirming "slavery is bad" sensibility is fine, but it's certainly not superior to the alternative.

Reader — November 6, 2013

I haven't seen either yet, but I think this is an inapt comparison. "Django Unchained" is inspired by a Spaghetti Western revenge fantasy series, also called "Django." A lot of people are probably quite willing to see a black guy star in a "comic book adolescent fantasy," just as they're happy to see a gorgeous, dark-skinned black woman star in the soapy, political thriller series that is "Scandal." Slightly silly or not, these are firsts.

TMI — November 9, 2013

Some people enjoy seeing the slave masters get brutally killed, others enjoy watching the slaves get slowly whipped and killed. We all have our own sado-sexual masochistic revenge fantasy, don't we? Praise be to God!

rosie1843 — January 7, 2014

"Django Unchained" is not even a revenge movie. It's about a former slave who desires to find his wife and free her from slavery by any means possible.

Just because it's a work of fiction, instead of a biopic like "12 YEARS A SLAVE", does not mean it's a terrible film. I am so sick and tired of self-righteous critics who blind themselves from certain details in order to get on their damn soap boxes and moralize to the rest of the world.

By the way, the depiction of antebellum America in "12 YEARS A SLAVE" wasn't completely accurate, especially in scenes that featured Northup at that Washington DC hotel, the murder of the slave named Robert aboard the ship that took Northup to Louisiana, and the Mistress Shaw character. If you were a student of history, you would know this.