Cross-posted at The Huffington Post and Pacific Standard.

Sociologist Alexandria Walton Radford has some new research that is rather disheartening. Radford was interested in the college choices of ambitious and high-performing high school students from different class backgrounds. Using a data set with about 900 high school valedictorians, she asked whether students applied to highly selective colleges, if they got in, and whether they matriculated.

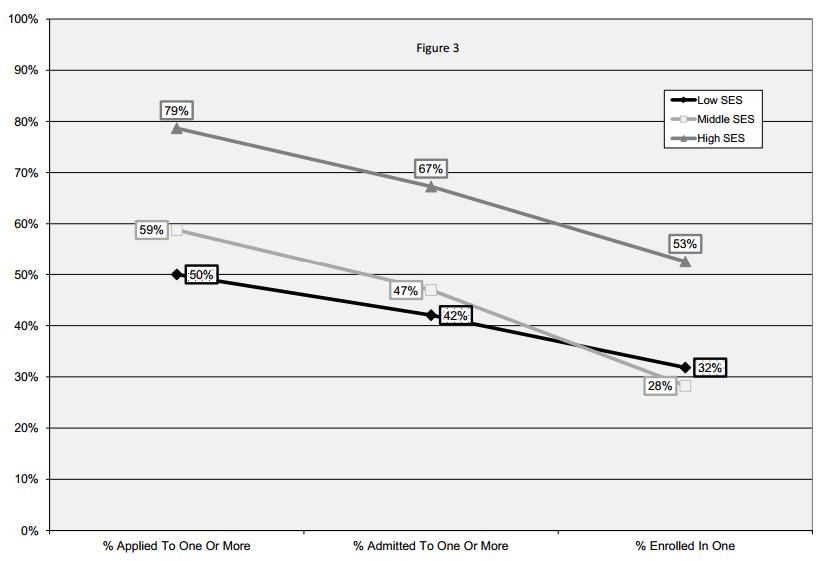

She found a stark class difference on all these variables, especially between high socioeconomic status (SES) students and everyone else. Over three-quarters of high SES valedictorians (79%) applied to at least one highly selective college. In contrast, only 59% of middle SES and 50% of low SES valedictorians did the same. Admission and matriculation rates followed suit.

Interviews with a smaller group of these valedictorians shed light on why we see such dramatic differences in the application choices of low, middle, and high SES students. Radford explains that most students applied to schools with which they were already familiar. High SES students were much more likely to know people who had attended highly selective colleges, so they were more comfortable applying. They also felt more confident that they’d be successful at such an institution; less affluent students were more intimidated by these schools.

Radford concludes by arguing that it’s a mistake to leave decisions about whether and how to apply for college admission to families. Doing so, she writes, “allows the advantages (and disadvantages) of one generation to be passed on to the next generation.” School-based college guidance would go some way towards evening out the differences and making higher education admissions more meritocratic.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 39

Yrro Simyarin — May 16, 2013

As a lower-middle-class valedictorian myself, my school choice came down to two options - a selective school where I would receive a need based full tuition scholarship, or a solid state school where I would receive a full ride academic scholarship. Using the university's own cost of living calculations, I would have graduated from the selective school $60,000 in debt, in exchange for marginally better classes, and having more friends whose parents were rich. Personally, at least, it was the right choice.

AcademicLurker — May 16, 2013

I would have expected more high SES valedictorians to have been accepted & matriculated at selective colleges. Where are they going instead?

Patty — May 16, 2013

I think Ms. Radford is working under the assumption, however, that highly selective schools are necessarily better than less-selective schools. Clearly that is not always the case, even for very motivated students. Also, I am surprised that she does not bring up cost. A less-selective school is likely to give a promising student more scholarship money, and lower SES family may not have the resources to transport their child to a more distant, more-selective school, even if all housing costs are covered. Finally, while I don't have any data to support this, anecdonatlly I suspect that lower SES students are much more likely to work at least part-time while studying and possibly continue to carry responsibilities in the home, making commuting while living at their parents' house much more likely and therefore preferring nearby schools.

Japaniard — May 16, 2013

I'm more interested in the fact that, despite more middle SES students being admitted to selective colleges than low SES students, fewer middle SES students actually end up enrolled.

This seems to be indicative of the problems with rising tuition rates. Even if you are smart enough to get in, only those rich enough to pay or poor enough to not have to pay end up enrolling, while those in the middle get left behind by FAFSA

Gman E Willikers — May 16, 2013

Speaking as a US citizen, improving the erosion we've experienced in social mobility should be considered a national priority. Without social mobility, the American dream is dead. This study is really eye opening. There is likely a cultural rationale but, intuitively, I can't help but think that the economic rationale is the predominant force at work here.

Most of the high achieving kids from lower socioeconomic classes simply do not, on their own, have the $s to pay the cost of many highly competitive institutions. They may be unaware of the tremendous amount of assistance that is available. Good school counselors could help these kids by advising them, in the strongest terms, to NOT rule out any school simply on the basis of family economic capacity. Speaking from first hand knowledge, there really is a stunning amount of aid available at many of these highly competitive schools. With that said, the process required to secure available funding can be so daunting, that many kids (or their guardians) simply turn away after taking one look. I am sure that because of this fact, much of the aid goes to the children of the well-educated, or culturally privileged, who either temporarily or by design are engaged in work that pays poorly. These kids of "poor" culturally privileged parents are able to receive critical help from their parents. Accordingly, it may be quite beneficial to the goal of social mobility to also provide some resource that helps ensure that high achieving kids of economically and culturally underprivileged parents are given sufficient capacity to apply for the available assistance.

LauraD — May 16, 2013

I also think this has a lot to do with just how expensive college is. Even if the student has the grades to get into a more selective school, state schools are a much better bet for many students, particularly those in the middle, who can't afford a more selective school, but don't qualify for many scholarships or grants.

David Chapman — May 16, 2013

Just some musings: I don't doubt the factors like $$$ (future debt, need to work), family responsibilities, and so on (as others have mentioned). However, I'd want to see more on (a) the preparation part, (b) overall school SES, and, yep, (c) SAT scores in order to control for some potential factors.

Is the student prepared? The references discuss other studies, but I didn't see a lot of detail. I have known of valedictorians (or salutorians, etc.) who had high-class rankings, but were woefully unprepared for college (basically, did not understand HS/MS Algebra or had serious writing problems). The school may be a factor in the student's learning, hence the need to know (and control for) the school makeup and its possible effects (which might be collinear with the preparation issue). And... while the SAT is imperfect, it is what it is; how-well-did-this-sample-do wasn't addressed in this study (just references to other studies).

Fanny — May 16, 2013

I think this completely ignores the realities of true poverty. When you know you only have enough money to pay a single application fee, aren't you going to choose to apply to a school where you know you'll be accepted? Or to one that you can actually afford to travel to? Full-ride scholarships may pay tuition and even class fees, but they generally do not take into account all of the startup expenses like application fees, room and board during school breaks when campus accommodations are closed, or airfare/train tickets/other travel costs. And when you come from a background of poverty where you often have to make a choice between food and rent, "saving up" for these kinds of expenses isn't often an option, no matter how smart or talented you are.

sprockethawk — May 16, 2013

I think it's a mistake to lean on the notion that families should be less entrusted to make decisions about college applications, while leaving out the more obvious deterrents: money and networked privilege. It starts with the high fees elite colleges charge merely to process an application for entrance (this can be well in excess of $100 per application). It continues with question of how to afford the actual tuition at an elite college--not all students are offered full scholarships with room and board: most successful applicants, especially from underprivileged backgrounds, will still have to come with substantial monies from either usurious loans (making them serious debtors before they even begin a career) or else working many hours while attending school (which can have a deleterious affect on study habits). A second issue is alma mater influence. At least sometimes (and I suspect often) the influence of a recommending professor is paramount to a successful application, especially if the professor has "connections" to the school.

I know that from my own experience, coming from a background of poverty and want, I had to knock back an invite to attend Hampshire College, where I hoped to write a symphony, because the school had exhausted its scholarship funds by the time they accepted me and even taking out maximum loans would have been insufficient. I went on to study at a state university, where given a modest package of financial assistance I had to work substantial hours each week (paradoxically seeing my next year's aid package go down because of my previous year's extracurricular income) to maintain a breathing lifestyle--and still incurred thousands of dollars of debt to banks who began knocking on my door for payment soon after graduation. As I was finishing my undergraduate degree, graduating summa cum laude, I applied to about a half dozen grad schools, including Brandeis, BU, and BC. I didn't apply to Harvard because I couldn't afford the application fee at the time and because I didn't like the odds of getting in (my SATs were only about 1300). My favorite lit professor--and advisor--told me he could get me into Columbia, if I wanted. Well, I wanted, but still faced terrifying new loans to finance it, not to mention the cost of moving from Boston to New York. I got into BU and Brandeis, with full scholarships, and would have pursued my first choice of further studies in literature (my first of two majors), but again, living costs and associated study costs, financed by new loans, made me think twice. While I was still considering I got an offer from RPI to study philosophy (my second major)--an offer that included full tuition, room and board, and a TA--and I took their offer.

It's more complicated than your sociological graph would have it seem is all I'm saying. The availability of debt-free money was a serious determining factor in my scholastic choices and had nothing at all to do with any class self-image. And I'm certain that many others face similar born-into choices and obstacles.

gay steve — May 16, 2013

this is heterocentric

Britney — May 17, 2013

This paper further supports the findings from the 'Missing one-offs' study, and hit even closer to home when compared to my personal experience. As a valedictorian from a small school with a single parent earning <$25,000/year, I never even knew that I was allowed to apply to an elite college, let alone encouraged. I dreamed of going to Harvard, but I remember balking at the application fee, and feeling embarrassed to even entertain the idea, since I would surely get rejected (because at the end of the day, who was I? I wasn't some 'actual' smart kid from a good school, I was just a big fish in a little pond who couldn't compete with 'real' smart kids). I settled for a full-ride local state school (with a 4.0 GPA), and worked full time through my undergrad and masters to avoid taking out too much in loans. It wasn't until graduate school that I realized I still held on to the notion that there's 'poor people smart' and 'rich people smart,' an erroneous belief which prevented me from feeling like an equal around higher SES peers, or people from elite schools. It's taken awhile to get that chip off my shoulder, and it's sad that so many other poor kids with potential face the same challenges.

How Class Affects the College Choices of Even the Best Students — September 5, 2013

[...] post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner [...]

Comment — April 22, 2014

A couple of points that have not been made so far:

1. Low income college students do not develop strong social advantages merely by being around people who have those advantages.

2. Most highly selective schools require SAT subject tests in addition to the traditional SAT. Testing is expensive and waivers are not always communicated well to students who need them.

3. For many moderate to low income students, buying a winter wardrobe needed to attend top universities (Stanford and Caltech excepted of course) is a huge expense.

4. Some low income students may not find the most selective schools appealing because they do not want to be someone else's diversity experience.

5. Most low income people I know who went to prestige schools wound up in careers they would have been

able to enter pretty easily out of state or less prestigious schools

(teaching, law, and medicine). [Does anyone have systematic data comparing net worth for top h.s. students who went to mid-tier versus top tier schools 5, 10, 15 years out]