Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

While newspapers give a lot of ink to arguments about whether reducing the budget deficit will boost or reduce growth, they seem to have little interest in the related issue of whether economic growth really benefits the great majority.

David Cay Johnston, the Pulitzer Prize winning financial journalist, recently addressed this issue drawing on the work of economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty:

In 2011 entry into the top 10 percent… required an adjusted gross income of at least $110,651. The top 1 percent started at $366,623.

The top 1 percent enjoyed 81 percent of all the increased income since 2009. Just over half of the gains went to the top one-tenth of 1 percent, and 39 percent of the gains went to the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent.

Ponder that last fact for a moment — the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent, those making at least $7.97 million in 2011, enjoyed 39 percent of all the income gains in America.

So, 81 percent of all the new income generated from 2009 to 2011 was captured by the top 1 percent income earners, where income is defined as adjusted gross income, which refers to income minus deductions or taxable income. In other words, growth, even accelerated growth, is not going to do the majority much good if the economic structure remains the same.

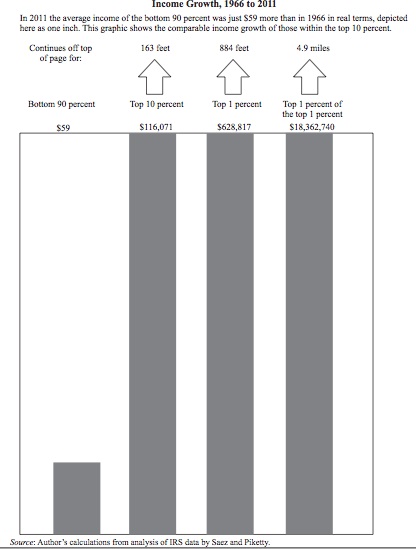

Johnston highlights the problem with our existing economic model with perhaps an even more shocking example. He compares the average income growth of the bottom 90 percent with the average income growth of the top 10 percent, 1 percent, and top 1 percent of the top 1 percent over the period 1966 to 2011.

It turns out that the average income of the bottom 90 percent rose by a miniscule $59 over the period (as measured in 2011 dollars). By comparison, the average income of the top 10 percent rose by $116,071, the average income of the top 1 percent rose by $628,817, and the average income of the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent increased by a whopping $18,362,740. In short, growth alone means little if the great majority of people are structurally excluded from the benefits.

In an effort to highlight this extreme disparity in adjusted income growth rates, Johnston suggests plotting the numbers on a chart, with $59, the amount gained by the bottom 90 percent, represented by a bar one inch high. As the chart below shows, the bar representing average gains for the top 10 percent would be 163 feet high, that for the top 1 percent would be 884 feet high, and that for the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent would be 4.9 miles high.

In sum, the real challenge facing the great majority of Americans is not figuring out how to make the economy growth faster. Rather, it is figuring out how to create space for a real debate about how to transform our economy so that growth will actually satisfy majority needs.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.

Comments 9

Tim — March 20, 2013

The problem with this analysis is that the individuals in the the top, middle, and bottom deciles change on a year to year basis. While this analysis can show that the 1% did this or those in the top 10% did that, over any 5 year period of time, the churn of people in the top 2 deciles (top 20%) and bottom 2 deciles is nearly 90%. The American economy is very dynamic. Individuals at the top, fall to the middle and bottom. Individuals at the bottom rise to the middle and the top.

MPS17 — March 20, 2013

I agree with the tenor of this post but it's very important to note that our system of progressive federal taxation means that all of Americans benefit from economic growth even when it is concentrated among the wealthiest. Indeed, I'd say this is the whole point of progressive taxation: to redistribute for the public good the wealth gains that our capital privileges tend to concentrate among the richest.

Typical analyses fail to see this because they typically fail to account for public services / entitlement programs among people's "income" or "consumption," but that's what they are. When a person receives Social Security it is as if they had purchased an annuity of corresponding value. These government programs are funded predominantly by the rich (because, of course, the rich receive such a high share of the income).

It's important to note this because government programs are the way we try to address this problem. It's like complaining about access to education in the US and ignoring the existence of public education.

Brutus — March 20, 2013

If the top 10% averaged +$116k each ,the top 1% averaged +$628k each and the top .01% averaged +$18,362k each, the top percent of a percent accounts for one third of the increase in the top 1% and one seventh of the increase in the top 10%.

We need a lot more granular information to do any meaningful analysis. Among that data would have to be the demographics of the top earners.

Gman E Willikers — March 21, 2013

Intuitively, this seems pretty simple. In a global economy, those with the greatest mobility have the greatest flexibility and will always do best. The wealthiest already have significant capital, and capital is the easiest thing to move around the globe chasing opportunity. Creating jobs at home will improve income across economic classes. The solution; however, is not so simple. Attempts to force wealth to stay "home" may work in the short term but will ultimately have adverse unintended consequences as new and potential wealth migrates elsewhere to avoid being trapped. Jobs creation will have to come through a combination of elimination of impediments and creation of incentives. Creation of incentives can be good but it forces choices today that have the potential to become impediments tomorrow (e.g., today's favorites have temporary demand/utility in the fast paced information age and continue to suck up available capital long past their expiration date because of their antiquated but still extant incentives). Elimination of impediments is the better option, particularly those impediments that are rigged as barriers to entry to protect those who have already entered (e.g., the multinationals).