We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

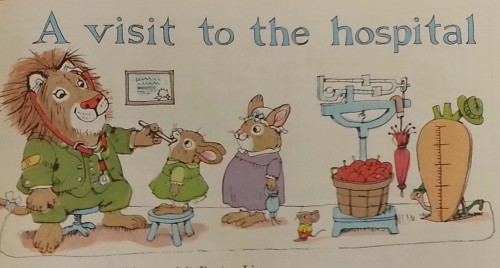

As children, many of us encountered Richard Scarry’s book, What Do People Do all Day? A classic kid’s book, it uses animals to represent the division of labor that exists in “Busytown.” The book is an example of a brilliant piece of analysis by sociologist John Levi Martin.

To oversimplify greatly: Martin analyzes nearly 300 children’s books and finds that there is a marked tendency for these texts to represent certain animals in particular kinds of jobs. Jobs that allow the occupant to exercise authority over others tend to be held by predatory animals (especially foxes), but never by “lower” animals (mice or pigs).

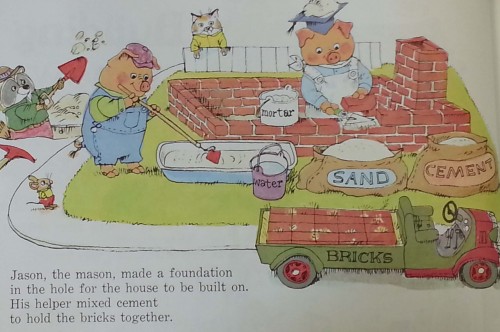

Pigs in particular are substantially over-represented in subordinate jobs (those with low skill and no authority), where their overweight bodies and (judging from the plots of these books) congenital stupidity seems to “naturally” equip them for subservient jobs. Here, see this additional image from Scarry’s book, showing construction work being performed by the above-mentioned swine.

In effect, Martin’s point is that there is a hidden language or code inscribed in children’s books, which teaches kids to view inequalities within the division of labor as a “natural” fact of life — that is, as a reflection of the inherent characteristics of the workers themselves. Young readers learn (without realizing it, of course) that some species-beings are simply better equipped to hold manual or service jobs, while other creatures ought to be professionals. Once this code is acquired by pre-school children, he suggests, it becomes exceedingly difficult to unlearn. As adults, then, we are already predisposed to accept the hierarchical, caste-based system of labor that characterizes the American workplace.

Steven Vallas is a professor of sociology at Northeastern University. He specializes in the sociology of work and employment. His most recent book, Work: A Critique, offers an overview and discussion of the sociological literatures on the topic. You can follow Steven at the blog Work in Progress.

Cross-posted at Work in Progress.

Comments 64

Rachel Keslensky - Last Res0rt — January 28, 2013

How much of this is consistently codified, though?

Only certain texts (like Maus) are explicit in associating certain races with certain species (including one excerpt where a prisoner was trying to convince his captors he was actually German instead of Jewish -- and for a single frame the "mouse" character is actually drawn as a cat!)

Likewise, I could see a pig being both illustrated as a menial worker (fat, dumb, messy) and a corporate CEO (ala Animal Farm, where the pigs were classed as politicians).

Yes, it's bad to make predator/prey relationships stand in for certain roles and relations, but I have to wonder how much of this is actually consistent.

mnkybrs — January 28, 2013

I didn't realize there were no foremen, project managers and site supervisors in the construction industry and every worker is the same as every other worker and no one exercises authority to others.

WG — January 28, 2013

Construction takes no skill and is done by stupid people? WTF? Pigs aren't fat? Is Steven trying to redefine reality to suit his needs?

Gman E Willikers — January 28, 2013

Could this also be construed as conditioning children to look upon all those in the "managerial class" as violent predators, and all those in the "laboring classes" as innocent victims who will eventually be "consumed" by their managers?

Elena — January 28, 2013

Here, see this additional image from Scarry’s book, showing construction work being performed by the above-mentioned swine.

This is the brick house. They had been building houses made of straw and sticks before, but bricks are so much better against wolves.

That said, I thought the image of pigs in children's literature was more towards a "stupid bourgeois" image, until you get to the "filthy capitalist" literature and traumatize the kids with Animal Farm. I definitely didn't see pigs as working class that much.

WRT that same image, is that a raccoon digging a hole? It would make so much more sense if it was a badger. At least badgers are burrowing animals :/

Children’s Books and Segregation in the Workplace » Sociological Images | digitalnews2000 — January 28, 2013

[...] on thesocietypages.org Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in [...]

Ali — January 28, 2013

I loved these books as a kid. But I remember thinking the pig was so industrious and clever to be building his own house. I don't think I felt any of the jobs were 'lowly'. (Scarry pun! LOL)

Maybe my regard for the job makes me read this differently.

Umlud — January 28, 2013

Yes, in the Babar series, it's all about this exact "hidden language or code inscribed in children's books". In the Babar series, we learn that elephants "ought to be professionals," because "jobs that allow the occupant to exercise authority over others [like Babar the king] tend to be held by predatory animals," which we all know elephants to be!

... oh, wait.

Okay, that one's an exception. Definitely, though with the Frog and Toad series, we can see two laze-about predators who represent upperclass toffs who go about just talking, reading, and riding bikes. Never an example of hard work between the two of these predatory animals who - since we know them to be predatory - must be characterized as being able "to exercise authority over others".

... oh, wait.

Okay, maybe the author is talking about the Berenstain Bears, you know that series with the corporate executive father and university professor mother and their two children who are in officer training school. Oh, wait... that's not right; the father is a carpenter who is clumsy and bumbling, the mother is a homemaker that gardens and makes quilts. You know... just like your average bears: in jobs that exercise authority over others.

... oh, wait.

Okay, maybe the author is trying to talk about how My Little Pony would be subservient to Thundercats? (I mean, I knew this to be true when I was a boy, even if my neighbor kept saying that I was stupid and a poopoo face for thinking that sort of thing. Still, what did she know?) The findings of this article indicate help indicate the inherent truth that - of the popular 1980s cartoons - Thundercats was the one that held the greatest authority over other animal-based cartoons, which were (in descending order of authority): Thundercats and Care Bears (and effective tie, since these are populated by top-predators), Garfield (who comes in next, since he's a tame predator that doesn't actually predate), Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (they totally destroy those peperoni pizzas), and finally My Little Pony (sorry, but they're all indolent herbivores).

... oh, wait.

I'm starting to scrape the barrel on my memories of childhood storybooks with animals making up the majority of the cast of characters... Does Curious George count? Or does he not count, since he is a monkey in a human world, and not an anthropomorphized monkey in an anthropomorphized world? What about Finn Family Moomintroll? Nah, those are fantasy creatures. And anyway, they're not majority-culture American, either. Probably, the Southwest Native American stories about coyote also don't count, either. Nor the Japanese stories about tanuki, swallows, or the animal companions of Momotaro. Nor Chinese stories like children's adaptation of the famous Journey to the West, which had two anthropomorphic animal characters (Sun Wukong and Zhu Baije) Nor German stories like the Brementown musicians.

... oh, wait, I think I get it now:

I must have been given the wrong books to have read to me as a child.

Larrycharleswilson — January 28, 2013

"Publish or Perish" The results are sometimes very amusing.

Alysonlucille — January 28, 2013

"To oversimplify greatly." Enough said. It doesn't take a scholar to recognize an industrious pig building a house out of bricks is a good thing. Predatory animals, especially foxes? Oh pulll-eeeeze. This is not codified into job prerequisites. This is a really big stretch and yes, oversimplified greatly. Now give us some substance and some real social critique. This is drivel.

Legolewdite — January 28, 2013

As the "full-time" father of a precocious two-year old, I find this piece resoundingly true - to the point that my wife and I have discussed the exact same phenomenon numerous times. Of course, my background is from a master's program in literary studies, so I'm not nearly as scientific about my "research." English isn't math. But I have seen a large sample: we read and reread about 30 different children's books each week for well over a year now. And there are many other ideologies at play in our selections as well; I've started a collection. Here I'm thinking of things like Curious George being an extremely racist text (it's essentially King Kong), or how reprehensible the pedagogy of the Pokey Little Puppy's mom is (leaving passive aggressive notes with the potential to cause eating disorders). Anyone read Margaret Wise Brown's The Important Book? "The important thing about a daisy is that it is white," and "the important thing about snow is that it is white." Really? Are these the most important things, Margaret?

It's unsurprising to me that many commenters here find this hard to believe though. Like criticizing Disney, people balk at what they find to be their seminal narratives, the stories of their childhood. Seems to me as though they're worried that if they pull at those particular pieces of their foundation that the whole structure of their identity might crumble...

Lori S. — January 28, 2013

a) I do think that in this case, pigs are building the (brick!) house as a reference to the Three Little Pigs. A better example would be in order here.

b) Which is not to say I don't completely concur with the underlying point.

c) Gender correlation is even stronger. I'm thinking children's clothes here. Boys get to wear (and be represented by) predators: lions, tigers, T. rex. Girls get to wear (and be represented by) prey: giraffes, zebras, bunnies. It's kind of disturbing after a while.

Agraymo — January 28, 2013

Oh, get real. Most of the children I worked with over 25 + years as a children's librarian didn't give any of that a thought. They knew they weren't animals and weren't expected to perform as such. They loved animal stories and, if chosen correctly, gained all sorts of positive values from books by Stephen Kellogg, Arnold Lobel, Mercer Mayer and others. We didn't take apart each book to analyze characters and their vocational choices. We enjoyed words and pictures and good art. I know many of my former students and what they are doing and, believe me, what I read to them in picture books has not seemed to influence their career choices. Worry about violence, hatred, discrimination....real problems...not animals dressed as construction workers.

manyfaces — January 28, 2013

What I've noticed in the children's books (especially Scarry) is that there are few, if any, white collar jobs at all. Supervisors though tend to be special animals. And special animals tend to be harder-to-draw predators like lions.

The more disturbing thing is the way gender roles are broken down. And that while any of the kids books are products of their time, I find myself slipping into that mode of thought when I read them. I've caught myself calling ANY women in a hospital a nurse unless specifically called out as a doctor (a white coat is not enough).

Of course the most disturbing thing in the Scarry books is seeing pigs (or, even worse, herbivores) eating things like ham, sausage, and other meat.

OSUProf — January 28, 2013

I have two issues with this post. First, is there a new article or book by Martin? Because the linked, full text article is from 2000. Hardly a new study. Second, again, is there a different article/book that the author is referencing? Because the linked text does not analyze 300 children's books. It only analyzes Richard Scarry's book, What Do People Do All Day. I do not think one can draw many generalizations regarding 'segregation in the workplace' based on ONE book published over 40 years ago.

In other words, I think this article is lacking some details or making claims that the original source material does not support.

Umlud — January 29, 2013

After thinking about this for a bit, I've come to realize that there is a major problem of ascribing these animals into the categories of "predator" and "prey" instead of "carnivores," "omnivores," and "herbivores." (Let alone talking about them in finer shades, such as making distinctions between "obligate carnivores" and "facultative carnivores.")

I find the generalized implications of "predator" and "prey" (as seen in the comments section and in the article) to be simplistic and kind of sloppy. Collapsing animals into only the categories of predator and prey fails to recognize the more complex nature of inter-species dynamics, such as:

A) evolutionary strategies of carnivore avoidance,

B1) presence of danger incurred by carnivores when hunting,

B2) ability of many herbivores to kill carnivores, and

C) social cues among groups of animals.

Where, then, are the omnivores? They're completely missing from the above assessment. What are the assumptions of the social roles that they play? For example, pigs are not merely docile, objectified "prey" species, but can be predators and scavengers themselves. Indeed, the very concept of a pig being a "prey" species is ludicrous when you think of wild and feral pigs: those suckers are dangerous to almost any hunter, much like hippos can easily tear up any potential threat, and are far from any idea of "prey" species that you can imagine.

What's Martin's justification of collapsing his assessment into the false dichotomy of "predator/prey"? Where are the assessments of the different types of carnivory (that then precipitate to the various forms of predation), herbivory (that make certain animals less or more prone to predation from the other locally present fauna), omnivory (are these animals "predator" or "prey" or both, but how could they be both if it's a binary classification?), and scavenging (recognizing the thorny point that you can't classify vultures, condors, and hyenas so easily into the "predator" OR "prey" categories)?

Furthermore, animal behavior is far more complex than functional feeding group (which I focused on here), but also include group/herd/pack formation vs. individual, levels of matricarchy vs. patriarchy, and a whole slew of things that animal behavior scientists study and any half-way interested 8 year old would already know something about. .... and which appear to be completely missing from Martin's "assessment".

So maybe there also ought to be an assessment of the ecological validity of the illustrators' (assuming that Martin looked at multiple illustrators' works) depictions of animals in conjuction with the pigeon-holing that Martin forces these illustrated animals into.

Edited to correctly reference John Levi Martin as the one who wrote the assessment of Scarry's book.

Ola — January 29, 2013

I'm not a sociologist, but all I know is if I could get a frickin' rabbit to do my laundry, I don't care if its a lady rabbit or a man rabbit or homobisexual rabbit. It's a frickin' rabbit that does laundry, and many people will pay good money for that kind of thing (especially if it comes with a happy ending).

However, if a fox were to do some wallpapering for me, I would certainly lock the 'fridge before I let them into the house. Am I a bigot?

lisa — January 30, 2013

I must say I'm a bit confused by Stephen's idea that construction is a menial job - it requires precision and quite a bit of knowledge to do well.

Andrew S — February 1, 2013

To be fair, the three little pigs did show they were very adept at building brick homes.

(I didn't read the other posts, in case someone else pointed this out already)

Stereotypes in Kids Books: Girl Animals have Eyelashes | SociologyFocus — February 4, 2013

[...] sociologists. They have been used to study not only gender, but also environmental messages and workplace segregation. Using the 10 books you selected in the previous question, what other themes or messages emerge [...]

Ken — February 25, 2013

Or as the pigs in Animal Farm had it:

"All animals are equal. Some are more equal than others."

Dječje knjige i segregacija na radnom mjestu » Centar za društveno-humanistička istraživanja — March 13, 2013

[...] i workinprogress.org, inače specijaliziran za sociologiju rada i zapošljavanja, u svom članku Dječje knjige i segregacija na radnom mjestu osvrće se na analizu dječjih knjiga Johna Levija Martina pod naslovom What do animals do all day? [...]

Stereotypes in Kids Books: Girl Animals have Eyelashes | Stephanie Medley-Rath, Ph.D. — July 11, 2013

[...] sociologists. They have been used to study not only gender, but also environmental messages andworkplace segregation. Using the 10 books you selected in the previous question, what other themes or messages emerge [...]

Ellen — December 28, 2013

I read hundreds of children's books to my children, later became a children's librarian, and of course came across sexist, racist, or otherwise objectional books while trying to make selections, but come on folks, sometimes a book is just a book, no hidden agenda intended.

[links] Link salad says, “Son can you play me a memory, I’m not really sure how it goes.” | jlake.com — December 29, 2013

[…] Children’s Books and Segregation in the Workplace […]

kafkette — February 12, 2014

you dont see that yr middle class devaluing of construction workers, etc & ect, informs what you are seeing?

Meet Dinglebat, P. Brain and Nutter: The Academics in Kid’s Picture Books — March 27, 2014

[…] there is a hidden language or code inscribed in children’s books, which teaches kids to view inequalities within the division of labor as a “natural” fact of life – that is, as a reflection of the inherent characteristics of the workers themselves. Young readers learn (without realizing it, of course) that some… are simply better equipped to hold manual or service jobs, while other[s]… ought to be professionals. Once this code is acquired by pre-school children… it becomes exceedingly difficult to unlearn. As adults, then, we are already predisposed to accept the hierarchical, caste-based system of labor that characterizes the… workplace. [link] […]

Nexage — March 21, 2022

Nice post!!

Pipin — April 4, 2023

Pigs are as smart as dogs and yet we eat them. I think this is probably more offensive to them than being portrait as strong, outdoorsy labourers, who are indeed underpaid and undervalued in a society where waffling can pay more than being a nurse.

Seriously though, as someone who grew up in relative poverty several decades ago I do understand the very limited vision working class kids can inherit from parents. It is a real disadvantage when compared to middle and upper class kids who grow up with more safety, help and aspirations. Some of their kids may even study sociology and try to change things, they're not all bad, but how serious will they be once they get older and have houses and cash to spend in fancy restaurants remains up for discussion. If these children's books, I haven't read Scarry, make any difference or not....

reynoldsfinley — August 23, 2025

It’s interesting how conversations about children’s books often reveal deeper issues, like how workplaces can unintentionally reflect segregation or bias. The way stories are told to kids really does shape how they view fairness and inclusivity later on. I noticed this when juggling my own assignments and trying to balance different perspectives in my writing. Honestly, that’s when I started looking for reliable essay writers uk who could help me sharpen my arguments and structure things more clearly. It felt less like outsourcing and more like having a mentor who knew how to turn scattered ideas into something cohesive.