Cross-posted at PolicyMic and Racialicious.

In 1984 the U.S. began its ongoing experiment with private prisons. Between 1990 and 2009, the inmate population of private prisons grew by 1,664% (source). Today approximately 130,000 people are incarcerated by for-profit companies. In 2010, annual revenues for two largest companies — Corrections Corporation of America and the GEO Group — were nearly $3 billion.

Companies that house prisoners for profit have a perverse incentive to increase the prison population by passing more laws, policing more heavily, sentencing more harshly, and denying parole. Likewise, there’s no motivation to rehabilitate prisoners; doing so is expensive, cuts into their profits, and decreases the likelihood that any individual will be back in the prison system. Accordingly, state prisons are much more likely than private prisons to offer programs that help prisoners: psychological interventions, drug and alcohol counseling, coursework towards high school or college diplomas, job training, etc.

What is good for private prisons, in other words, is what is bad for individuals, their families, their communities, and our country.

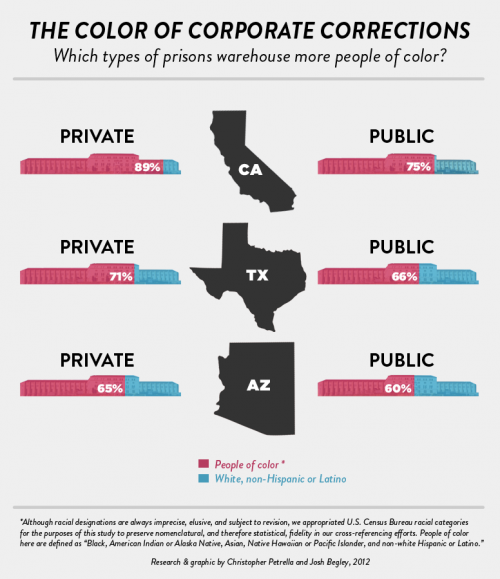

This is a deeply unethical system and new research shows that, in addition to being disproportionately incarcerated, racial minorities and immigrants are disproportionately housed in private prisons. Looking at three states with some of the largest prison populations — California, Texas, and Arizona — graduate student Christopher Petrella reports that racial minorities are over-represented in private prisons by an additional 12%; his colleague, Josh Begley, put together this infographic:

This means that, insofar as U.S. state governments are making an effort to rehabilitate the prison population, those efforts are disproportionately aimed at white inmates. Petrella argues that this translates into a public disinvestment in the lives of minorities and their communities.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 24

Race, Rehabilitation, and the Private Prison Industry » Sociological Images | digitalnews2000 — January 25, 2013

[...] on thesocietypages.org Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in [...]

Yrro Simyarin — January 25, 2013

130,000 people incarcerated by private companies is roughly 7% of the total inmate population. Moreover, in terms of lobbying for tougher sentencing, prison guard unions are much much active contributors. This isn't to make an argument *for* private prisons, just to say that there are much stronger influences on the problems of criminalization and increased penalties stated. Prison guards and their unions face similarly perverse incentives, and hold more power (at least currently). There are roughly half a million prison guards in the US, and public and private prisons both employ members of the same unions.

http://www.volokh.com/2013/01/10/the-effect-of-privatization-on-the-public-and-private-prison-lobbies/

http://www.doc.state.ok.us/maps/us_priv.htm

I get an error when I try to read the linked research paper. But I would also think that looking at what types of corrections facilities, what types of criminals they house, and where they are located would all be important in making this kind of analysis.

pduggie — January 25, 2013

"Companies that house prisoners for profit have a perverse incentive to increase the prison population by passing more laws, policing more heavily, sentencing more harshly, and denying parole"

Companies don't pass laws or police anyone. Are you saying that they lobby for more laws and heavy policing? Is there actually any evidence that they do this, or it it just speculation based on the idea they would have an incentive to do so?

Like at a hearing about decriminalizing drugs, does a representative of a private prison actually show up and testify? what does the representative say?'

"Petrella argues that this translates into a public disinvestment in the lives of minorities and their communities."

Does this "translate"* to the best way to invest in the lives of minorities and their communities is to deal with those imprisoned? Aren't they just a tiny minority of such communities?

*(what does 'translate' mean in this case anyway? That there was a 'coded' statement made?)

Flaming Iguanas — January 26, 2013

Hello?! Angela Davis anyone? I was so surprise to see no mention of her in this article and in the comments! This is not only alarming as it perpetrates the systemic erasure of the scholarship and thinking of women of color, but it also so damn wrong given the amount of work that Davis has done on this very same topic and the invaluable contribution she has brought to this field of studies.

[I was somehow able to access the cited article, but I was unable to find a single reference to Angela Davis, not even the usual token footnote at the end of the paper.]

You can find one of her brilliant articles, "

Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial

Complex," here: http://colorlines.com/archives/1998/09/masked_racism_reflections_on_the_prison_industrial_complex.html

I wrote a brief summary of this article for a paper a few weeks ago (I am an undergrad in Canada). For those who are unfamiliar with it, I thought it'd be good to include it (please mind that English is not my first language, so my apologies if it does not read as smoothly as is should):

"In this interview for Colorlines.com, Angela Davis

shares her knowledge of, and perspective on, the Prison Industrial Complex

(PIC) in North America. First, she argues that aside from her own abolitionist

stance, it is now essentially undeniable that an understanding of the aggressive

politics of imprisonment in North America, and in particular in the U.S., are

indivisible from an analysis of systemic and structural racism (Davis, 1998, p.

1). Moreover she discusses the notion of “profitable punishment,” wherein “the

political economy of prisons relies on racialized assumptions of criminality

[…] and on racist practices in arrest, conviction, and sentencing patterns”

(Davis, 1998, p. 2). According to Davis, there are multiple ways through which

the PIC becomes a site for profit: through the direct impoverishment of

prisoners, and, more indirectly, through the systemic impoverishment of

prisoner communities, which are predominantly communities of color (Davis,

1998, p. 2); through prison privatization, which not only requires less

government and social responsibility, but also holds stock value (Davis, 1998,

p. 3); through the physical expansion of the PIC and thus, the enrichment of construction

industries (Davis, 1998, p. 3); through unpaid or underpaid prisoners’ labor

(Davis, 1998, p. 4); and through the disproportionate draining of “social

wealth” and social welfare funds (Davis, 1998, p. 4)."

As for the authors of SI [you wrote: "insofar as U.S. state governments are making an effort

to rehabilitation the prison population, those efforts are

disproportionately aimed at white inmates"], I would be very careful with suggesting that state prisons are more invested (or invested at all) into rehabilitation, whatever that even means.

I find the whole concept of rehabilitation within the PIC to be especially deceptive, given that I do not believe that there is anything rehabilitating at all in the prison system. It's like, first you place people in a significantly violent environment

where they are constantly at risk of abuse and they have a exposure to

drugs, and then you offer them counseling and drugs "rehabilitation"

programs. How screwed up is that? I actually know of people who started using drugs in prison for the first time, and became addicted ever since. I think that this idea of prison "rehabilitation" is part of an aggressive neoliberal propaganda, which wants to make us believe that targeted policing and increased arrest rates are actually meant to "help criminals off the streets" and "rehabilitate" them into society, while keeping "us" (read white citizen, middle class, heterosexual nucleus families) safe. As Davis has argued repeatedly throughout her career and life, just as you cannot separate race, class and gender from an analysis of criminality, you cannot ignore these factors also in analysis of the PIC. The bottom line is that it doesn't really matter whether a prison is private or state funded (other than from the material profit that it gains from prisoner's incarceration); its rehabilitation narrative functions as very convenient cover-up for an atmosphere, which instead of "curing" or "helping" people, it ends up facilitating the brutal terrorizing and abusing of prisoners, while keeping them divided from their - predominantly poor and racialized - communities and loved ones. Doesn't this sound like a modern divide and conquer?

GT Tobin — January 26, 2013

There are a large proportion of ethnic minorities incarcerated. The fact that many live in poorer neighborhoods makes them more vulnerable as there is often a higher police presence and the young people/adults are being targeted. Notice very few kids from high class neighborhoods in the justice system. Police have great power in deciding if a juvenile will go straight home or to juvenile hall. People in better neighborhoods can afford private attorneys. Many ethnic minorities have no funding and often language barriers. A young girl in GRF rehab center in San Diego in 2010 had to learn all the states before being released as part of her 21 step program. Her English was poor she was unfamiliar with the all of the States,felt this was very racist and cruel. A 14 year old Hispanic girl incarcerated for prostitution. Who is the victim here? These young people are victims of the system. It is a big money making business. Home supervision, court fines, restitution, Jail time. All paid for by parents, who are normally low income workers and struggle to pay back, plus credit is affected. Family life disrupted/destroyed education interrupted as mostly for short jail spells school work only accounts for electives. Children return to school behind and then have to catch up ! Let us find a better way why target ethnic groups and low income families who struggle to survive and keep family life together? Let us educate the educators and law enforcement on profiling, not all kids are bad because they have a dark" hoodie" on and a tatoo!!

Ruth

The Short List 2/1/13 | Juvenile In Justice — February 1, 2013

[...] via the Society Pages: ‘Race, Rehabilitation, and the Private Prison Industry’ [...]

Sponsoring a Florida College Football Team Can’t Whitewash a Private Prison Company’s Atrocious Record | ACLU of Florida — February 22, 2013

[...] ages of 18 and 29. (Indeed, one researcher recently found that African Americans and Latinos are even more overrepresented in private prisons than public prisons.). So the FAU Owls football team (most of whom are [...]

ACLU of Florida – Dev Site — February 22, 2013

[...] ages of 18 and 29. (Indeed, one researcher recently found that African Americans and Latinos are even more overrepresented in private prisons than public prisons.). So the FAU Owls football team (most of whom are [...]

Opinion: Private prison lobby pushes for tougher immigration enforcement to increase their profits — February 22, 2013

[...] The private prison business is worth a lot of money, with The GEO Group and CCA alone worth over 3 billion dollars. Collaborating with the government to expand the prison population is a sure way to line the pockets of its investors and minorities are lining up as partners in a business that disproportionately targets Latinos and African-Americans. [...]

Sponsoring a Florida College Football Team Can’t Whitewash a Private Prison Company’s Atrocious Record | The Tallahassee O — February 24, 2013

[...] ages of 18 and 29. (Indeed, one researcher recently found that African Americans and Latinos are even more overrepresented in private prisons than public prisons.). So the FAU Owls football team (most of whom are [...]

Prisoners of Color Have Less Access to Education Than White Prisoners | canacast.networks.beta — March 15, 2013

[...] it away, Dr. Lisa Wade of Occidental [...]

African American Men and the Privatization of Prisons – AS THE CROW FLIES — June 14, 2013

[...] Private prisons are an enigma. The modern era of prison privatization began in the US in the 1980s.This included the taking over of prisons, jails and detention centers, once funded and controlled by individual state and / or the federal government.The settings where one finds these jails and prisons is primarily below the “Mason/Dixon Line”, in the south.Professor Christopher Petrella put it thus:Private prisons and prison labor factories alike are overwhelmingly concentrated in former Confederate states, states that once held the greatest number of black bodies in bondage and were among the last to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. … [T]he private punishment industry continues to represent an experiment in racialized profiteering with a basis in U.S. slavery and convict leasing. [...]

Racial Disparity in the U.S. Justice System | Accidental Relevance — December 13, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2013/01/25/race-rehabilitation-and-the-private-prison-industry/ […]

Laura Bonham: No Justice for Inmates, in Schools or Prisons | Independent Political Report — March 9, 2015

[…] Evidence shows the US prison system is becoming more and more privatized and with this comes a disincentive to rehabilitate prisoners and maintain or increase recidivism rates. The corporatization of the prison system demands profit, and that requires prisoners in cells and the bilking of taxpayers for services which can be provided more cheaply by the state. The goal is to keep building more prisons to warehouse more prisoners, and to pass more and more laws criminalizing behavior, which target poor and working people and people of color at an alarmingly higher rate than in richer white communities. According to the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), “In 2010, black men were incarcerated at a rate of 3,074 per 100,000 residents; Latinos were incarcerated at 1,258 per 100,000, and white men were incarcerated at 459 per 100,000.” […]

Noel Moran — November 1, 2019

My name is Noel Moran, i would like to invite you to our Growth Alliance event on the 29th November in Portsmouth. we are stone believers of creating rehabilitative climates, within prisons and the community and would like you to be share our alliance and support people in personal growth.

The link to the event:

https://www.penalreformsolutions.com/the-growth-alliance

for further information please don't hesitate to contact me.

Very kind regard

1 — April 28, 2020

HECTOR BELLERIN prefers a move to Manchester City over a return to Barcelona because he does not want to repeat Cesc Fabregas’ mistake, according to reports.