Though laws varied, American slaves generally could not legally marry. They were the subject of contracts, legally barred from entering into contracts themselves. And while some enslavers encouraged their slaves to form romantic relationships because such relationships discouraged running away, slave families were always at risk of being torn apart at the whims of the “master.”

On this day in 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that ended slavery for all people in territories that were under Union control. Two years later, the Thirteenth Amendment amended the constitution to prohibit slavery. The next year, two newly-freed now ex-slaves, Thomas and Jane Taylor, were married in Kentucky.

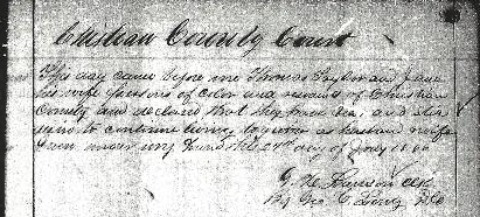

Text:

This day came before me Thomas Taylor and Jane, his wife, persons of color and servants of Christian County and declared that they have been and still aim to continue living together as husband and wife. Given under my hand this 27th day of July 1866.

G.W. Lawson, Clerk

Geo. C. Long, D.C.

Thomas and Jane are the great-great-great-grandparents of Tami, who blogs at What Tami Said. They had been together for many years before they were given the opportunity to marry and had two children. According to Dr. Tera Hunter at NPR, they were one of many newly-freed couples to marry in the years after the abolishment of slavery extended them the right. By 1900, she explains, marriage would be “nearly universal” among American blacks.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 21

Ruthi — September 22, 2012

I think what you've said about the Emancipation Proclamation is a bit misleading. Officially, it prohibited slavery in Confederate states, although of course this meant in practice that only those slaves in the Union controlled areas of Confederate states were actually freed. Lincoln signed it as a war measure, because he believe that he needed to do this to win the war, NOT because he wanted to further human rights.

Skada — September 22, 2012

I agree that this is a bit misleading. One, as Ruthi mentioned, many southern states resisted the proclamation. Here in Texas, we don't celebrate Sept. 22nd because it didn't do anything. We celebrate Juneteenth (June 19, 1865), which occurred years later. And it didn't happen on its own, either. It took a Union general showing up with 2,000 troops in Galveston to start a military take-over of the state to force emancipation before Texas finally let go of the slaves.

And two, as far as Lincoln and human rights goes, so many people decide to completely ignore American Indians. Lincoln oversaw the largest mass execution in the U.S. after capturing hundreds of Dakota people who fought back after Lincoln broke multiple treaties (Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and the Treaty of Mendota) and took military action on lands promised to the Dakota people. So whatever his reasons for signing the Emancipation Proclamation, it's important to remember his policies and violence toward Native people.

Anyway, the original thought of this is really cool -- looking into some of the first marriage between freed slaves and how that could change someone's life. And I'm glad we're talking about it. But I wish we could acknowledge some of these other things as part of the background and context of the post.

Pam — September 22, 2012

I think Lisa got it backwards. The Emancipation Proclamation applied to states still in rebellion. Apart from the threat, "give up or we will end slavery," the practical effect was to give slaves an incentive to run away, as they would be treated as free by the US Army. It also is seen by many historians as making the war "about slavery" and improving support for the Union side. So not totally irrelevant to ending slavery, but did not actually free anyone directly.

Yrro Simyarin — September 22, 2012

Really to cool see how important the institution of marriage was to those people, who had been denied it so long.

Emily — September 23, 2012

It's amazing to think it has already been over 100 years since African-Americans were so marginalized that they did not even have the right to marry (given, that was not where their struggles ended, of course). To many Americans, it seems ridiculous that they were ever kept from marrying, as it's such a basic right, and is based off of basic human emotion. It makes me wonder when, in the future, people will look back on our time and think "wow, it took them that long to begin even supporting gay marriage?" And even further, will polygamy ever be discounted as a heinous crime? Marriage as an institution will obviously continue to evolve, but to what extent? It's amazing how society's views on what's acceptable have evolved, even in a short 150 (or long, depending on how you look at it) years.