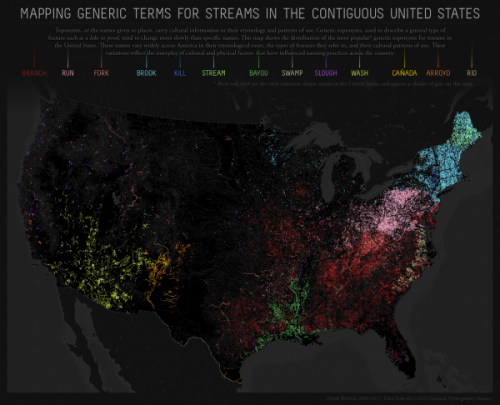

Dolores R. sent a link to a map created by Derek Watkins to show how the names given to geographic features reflect cultural patterns. Using a database of names officially accepted by the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, Watkins mapped generic terms used in the names of streams (excluding “creek” and “river,” which are commonly used throughout the U.S and were plotted in a gray that fades into the background):

The generic terms reflect historical immigration patterns. “Kill” appears in areas of New York originally settled by the Dutch; “cañada,” “arroyo,” and “río” indicate areas of Spanish exploration and settlement in the Southwest; of course, Louisiana and the surrounding area still reflects its French heritage through the term “bayou.”

The map reflects internal migration and cultural diffusion within the U.S., as well. For instance, Watkins suggests that the patch of red in southwest Wisconsin, indicating the use of “branch,” may be due to the lead mining boom in the early 1800s. Lead mining attracted Appalachian miners to the area, and they may have influenced local naming practices, bringing along terms common in Appalachia.

For more on the interconnections between geographic names or terms and larger cultural patterns, Watkins suggests reading Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States, by George Stewart (2008). Another excellent source is Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache, by Keith Basso (1996).

Comments 9

Anonymous — December 7, 2011

It's sort of a historical linguistic dogma that place names tend to retain their original pronunciation long after a change in local language.

A good example of this is the Picketwire River. First discovered by French speakers who named it "Purgatoire" because the area was so hot. Rather than directly translating to "Purgatory", the pronunciation was retained and shaped to fit English in "Picketwire".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purgatoire_River

Elena — December 7, 2011

By the way, in Spain, "cañada" usually means an established cattle track or drovers' road, rather than a course of water. The cañadas reales were established by Alfonso I of Castile in 1273.

In turn, bodies of water get their names from Latin/ Low Latin (río from rius, torrente from torrens, arroyo from arrugia, fuente from fons, and so on) or Arabic: the guadi- in river names like Guadiana or Guadalquivir, and plenty of words like rambla, albufera, acequia or azud. There's a special wealth of words from Arabic for terms related to irrigation technology, for the obvious historical reason that it was imported from the Middle East.

As for the river names themselves, in absence of a later rename, they tend to have Prerroman origins and often dubious etymologies. Anyway, the two rivers quoted above mean "River of Ducks" (wadi- + flumen anae) in Latin and Arabic, and "Stony river" (wadi al kibir) in Arabic (formerly Baits/ Baetis/ Betis, from the Phoenician, and giving its name to the Baetica province in Roman times). As for the other main rivers, nobody is too sure about the origin of the names of the Ebro or the Duero, and the Tajo would come from the Latin word taxus, "yew".

There's another wadi- name that you might recognise: Guadalupe, even if the Spanish river itself is not particularly notable. The Spanish wikipedia gives it an etymology from wad al-luben, "Hidden river", though.

Feral — December 7, 2011

Very interesting. Just as a side note though, I've never heard of "bayou" used in France for anything other than Louisiana's territory. Apparently "Bayou" isn't a French word, it seems to comes from the Choctaw word "bayuk" ("small stream").

Lunad — December 7, 2011

I'm interested in the regional difference between "run" and "brook" (pink and light blue). Yes, they are separated by the New York Dutch influences, but weren't they both mainly British settlement initially?

Anonymous — December 7, 2011

Pretty much none of the moving bodies of water have any of these appendicies in my neck of the woods, though Central VA does have an occasional "Run" or "Branch" in my experience. But who can compete with the fact that we have major roads called things like "Rio Road" (pronounced Rye-oh) or towns like "Buena Vista" (bueh-neh Vhis-tah) - I wonder how much other people's regional accents mess up even the cultural background. I had been taking Spanish for years before I saw the connection with Rio.

HQB — December 8, 2011

No creeks?

Elizabeth Archuleta — December 14, 2011

So I hope he doesn't exclude the original geographic names that the Indigenous peoples used before immigrants from England, Spain, and other western European countries mostly erased them.

Shameless pluggery and linkery-pokery. « Christian A. Young's Dimlight Archive — December 15, 2011

[...] An interesting graphic displaying regional distribution of place names that reflect cultural patterns in the US. Obviously, a significant portion of these names were imposed by European settlers, but I've been [...]